“Trump’s golden age looks an awful lot like a new Gilded Age,” wrote Politico this month, reflecting on the second inauguration of the United States’ president, prominently attended by tech billionaires. The day after that inauguration, historian Beverly Gage “couldn’t stop thinking about the Gilded Age” and its “rapid technological change as well as stark inequality, corporate graft and violent clashes between workers and bosses”.

But what was the Gilded Age – and does the comparison hold up?

The term, which spans the 1870s–1890s, came from an 1873 novel by celebrated satirist Mark Twain, The Gilded Age: A Tale of To-Day, co-written with journalist and neighbour Charles Dudley Warner. It meant a nation that glittered from its growth and the accumulation of economic power by the extremely wealthy. The title referenced Shakespeare’s King John, in which the Earl of Salisbury states, “To gild refined gold, to paint the lily […] is wasteful and ridiculous excess” (Act IV, scene 2).

Trump himself has cited this era as an aspiration. “We were at our richest from 1870 to 1913. That’s when we were a tariff country. And then they went to an income tax concept,” Trump said, days after taking office. “It’s fine. It’s OK. But it would have been very much better.”

Experts on the era, however, say he is idealising “a time rife with government and business corruption, social turmoil and inequality”, and “dramatically overestimating” the role of tariffs.

“The most astonishing thing for historians is that nobody in the Gilded Age economy – except for the very rich – wanted to live in the Gilded Age economy,” said Richard White, emeritus professor of history at Stanford University.

What is ‘the Gilded Age’?

For Twain and his co-writer, the message of their novel was plain: the early 1870s was full of gilded lilies – a period of wasteful excess, shady dealing in business, and political corruption.

The year 1872 saw a massive scandal over the railroads’ influence in politics, after “a sham construction company”, Crédit Mobilier, had been chartered to build the Union Pacific Railroad “by financing it with unmarketable bonds”.

Representative Oakes Ames of Massachusetts sold the shares at bargain rates to high-ranking House colleagues to secure political clout for the company. While most sold them quickly, representative James Brooks of New York (also a government director for Union Pacific Railroad) profited from a large block of shares.

Ames and Brooks were censured by the House in 1873 for using their political position for financial gain. The Crédit Mobilier Scandal, as it was called, became nationwide news.

The Gilded Age satirised such blatant pursuit of wealth. Its story centred around the members of the fictional Hawkins family, trying to get rich by selling their essentially worthless land in Tennessee under false pretences that misrepresented its value. The novel employs pathos as well as satire. An adopted daughter, Laura Hawkins, kills her married lover. She is tried and acquitted, but before her death, she feels guilty about her past behaviour.

Though amusing and clever as political and social satire, critics at the time were unimpressed by its rambling plot and uneven narrative – and it has never been regarded as great literature.

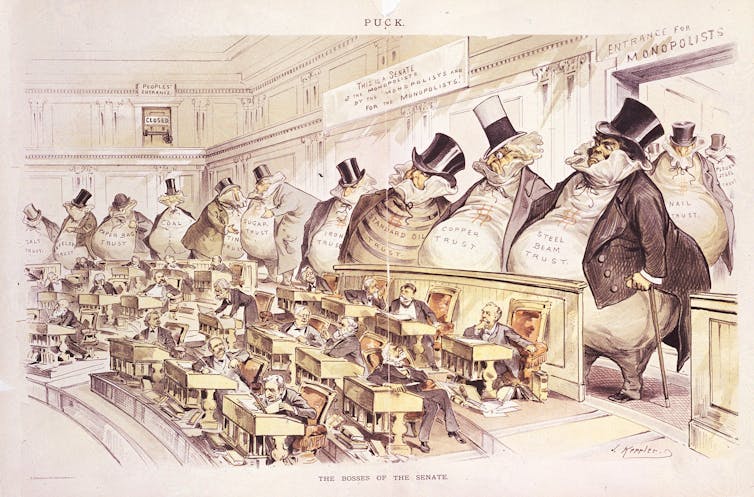

The Gilded Age, as an era, was a time of great economic booms and busts. It saw the accumulation of millions by the savvy and the rise of systemic corruption in the halls of Congress, state and local legislatures. Tammany Hall, the Democratic headquarters in New York, became almost a synonym for urban corruption in the awarding of municipal contracts.

Politics was trench warfare between the closely matched Democrats and Republicans. The themes of political battle included the supposed evils of the banking and credit system, how to remember the meaning of the recently ended American Civil War (the Democratic Party was still accused of being “the party of rebellion” in 1890), and how to incorporate formerly enslaved people into the body politic without giving them significant power. These are enduring issues.

The Gilded Age, as we think of it today, probably wasn’t set in concrete as an era covering the whole of the late 19th century until 1927, when Charles Austin Beard, then America’s most famous historian, plucked the term from Twain’s 1873 book for a chapter in his hugely influential textbook, The Rise of American Civilization, co-written with his wife, Mary Ritter Beard.

The Beards used the term to cover the period from approximately the late 1860s to the mid-1890s in domestic American history. The Civil War and Reconstruction period (1865–77) and the Gilded Age overlapped: corruption had already been present during the war, due to government contracts for the materials of war. Their book was assigned to several generations of mid-20th-century university and high school students in the US, and the term entered common usage.

Waves of progressive advance and reaction

Beard was an advocate of civil liberties and a sharp critic of the rich and politically powerful. He excoriated the plutocracy of the Gilded Age and their kitsch imitations of the European aristocracy’s tastes and possessions. But he quietly rejoiced in the underlying growth of a mass of people who loomed as a separate base for later progressivism in politics. His idea of periods of democratic and progressive advance on the one hand, and reaction on the other, has endured.

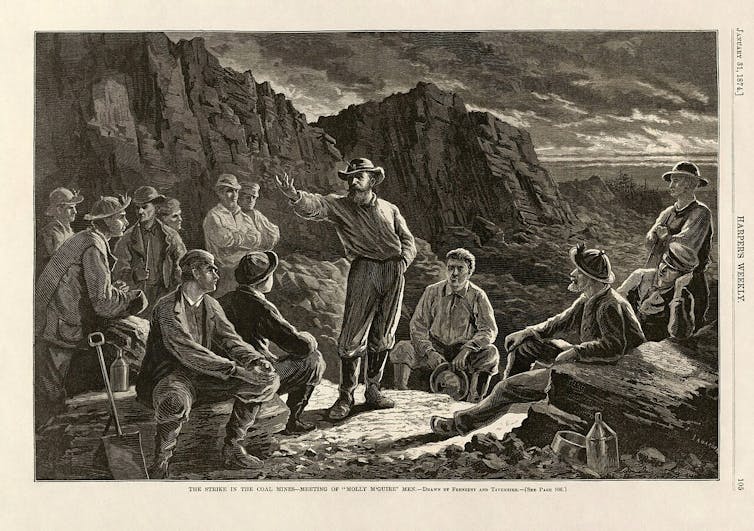

The extremes of the Gilded Age prompted a wave of progressive reform in the US between the 1890s and 1920. In 1890, came the first federal act that outlawed monopolistic business practices, enforced through the court system by Theodore Roosevelt, beginning in 1902.

Laws were introduced for protection of workers (mostly at the state level and through the courts), for direct election of senators, and for women’s suffrage. New laws also increased the regulation of industry, with measures like the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Federal Meat Inspection Act (both in 1906), and increased certain trade union rights, highlighted in Roosevelt’s intervention in the Anthracite Coal Mining Strike of 1902.

History doesn’t repeat; it may rhyme

Journalists, politicians and historians are talking about today’s “Gilded Age” as a repetition of the excessive wealth and power of the 1870s. However, Twain is sometimes quoted saying: “History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

No written record exists to show Twain ever used these exact words, but we can find the sentiment expressed in The Gilded Age, which seems to be where this gem originated. Twain and Warner actually wrote:

History never repeats itself, but the Kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends.

The original Gilded Age was a rising, yet flawed empire of the wealthy. Today’s second Gilded Age is a story of a plutocratic challenge for power in a democratic republic stuck in long-term anxieties over its potential decline – led by a showman helming a wild, unpredictable ride.

Another similarity between then and now is the attempt to legislate morality in the image of often ill-informed – but prone-to-vote – rural and small-town minorities. In the 1880s, one finely balanced moral struggle was over whether the US should have statewide alcohol prohibition. In some ways, this parallels debates over state anti-abortion legislation today.

There are more superficial similarities, too.

Donald Trump is one of only two presidents to serve two nonconsecutive terms. The other was Democrat Grover Cleveland, in the Gilded Age. But the differences between Trump and Cleveland also strike me.

Cleveland was well connected with the business community, but he was not a convicted felon. The worst he did was this: he had fathered an illegitimate child, and his indiscretion became the stuff of humorous campaign literature in 1884’s presidential contest. “Ma Ma, where’s My Pa?” chanted Republicans seeking to undermine his moral integrity within Victorian-era morality.

After Cleveland won, Democrats replied: “Gone to the White House, Ha, Ha, Ha.” Trivial campaigning issues are as old, almost, as the American republic itself.

The 1880s, the time of Grover and his reputedly crooked Republican alternative, James G. Blaine, saw morally suspect candidates rise to the surface. Democrats labelled Blaine “the continental liar from the state of Maine”, for using his influence to obtain favours from railroad companies. That pattern of extreme and often frivolous partisanship has been renewed since the Obama presidency.

American presidential politics – then as now – is gladiatorial sport, signifying little in the long-term history of the US except the recurrent failure of the nation to become more fully democratic, let alone a republic of equals. In the 1880s and 1890s, legalised racism was on the rise, most African Americans were losing the right to vote, and the women’s suffrage issue was only starting to be influential, later than in Australasia.

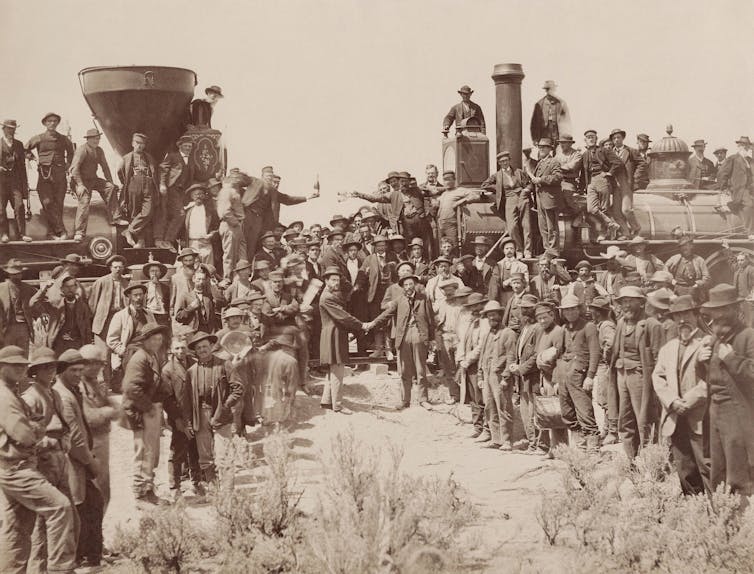

Like today, the Gilded Age was an era of a global communications revolution. Railways spread across North America, increasing from 35,000 miles of track in 1865 to 254,000 miles in 1916. A roll-out of submarine telegraph cables connecting the US to the world was also well underway. This pattern parallels our own communications revolution, with social media and now AI continuing to eclipse traditional media and in-person interaction.

In the Gilded Age, the economic greatness of America was laid out. It was pushed forward by rich entrepreneurs, otherwise known as robber barons: such as John D. Rockefeller in oil, Andrew Carnegie in steel, and George Westinghouse in electrical power and railroad brakes.

Today’s entrepreneurs are epitomised by the tech billionaires so prominent at Trump’s inauguration, including Meta co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Amazon owner Jeff Bezos, whose other enterprises include space company Blue Origin.

Chief among them is Elon Musk, owner of social media company X, SpaceX, and electric car company Tesla. Musk, who helped fund and organise Trump’s election campaign, has received “at least US$38 billion in government contracts, loans, subsidies and tax credits, often at critical moments”, according to the Washington Post.

Musk represents an escalation in the influence of the rich and powerful. He has an office in the White House, from which he runs the department of government efficiency (DOGE) and is regularly seen in the Oval Office itself. (However, a federal judge ruled this week that the Musk-led DOGE’s shutdown of USAID likely violated the US constitution, and ordered the administration to reverse some of the actions taken to dismantle the agency.)

Mark Twain would have felt at home – and yet not impressed – had he lived today.

Changing empires

Where the landscape looks most different today is our geopolitical context. The US in the Gilded Age was an up-and-coming force, but was not yet the dominant world power.

From 1865 to 1873, its industrial production would increase by 75%, putting the US ahead of every other nation save Britain in manufacturing output. Its economic advance, achieved under a security blanket of protectionism, created an enormous internal market for capitalist growth. Economists and economic historians differ on how influential the tariffs were, as they still do today.

Again, this sounds familiar, but the tariffs of the 19th century were mainly introduced as part of internal political machinations, seeking to bind voters to one party or the other. For Trump they are, more significantly, bargaining chips in a geopolitical contest.

China, the world’s second biggest economy, is the true enemy in this regard. In the 1890s, China was the site of the dying Qing Empire, with Britain the dominant world force.

In the 1890s, reporters from the world’s newspapers did not hang on every unnuanced word from a US president. Today is very different. The US president is the controversial leader of the “free world”, closely watched by all. He incites the inward-looking anxieties of a fractious republic at a moment when the so-called “unipolar order” (where one state is by far the most powerful) is disintegrating. He is trying to sustain America’s role, since the fall of the Soviet Union, as the undisputed, number-one power in the world.

In 1901, another American president marked the end of the Gilded Age. He was young, highly intelligent, Harvard educated and cosmopolitan. He had ideas about how to make America great, yet respected in the world. His name was Theodore Roosevelt, and he became president by accident.

It took an assassin’s bullet to the stomach of his predecessor, William McKinley, to give momentum to the post-Gilded Age progressive era. Roosevelt sought to corral and limit the power of those “malefactors of great wealth” who thrived in the Gilded Age. But he also wanted the US to become – and remain – a world-leading imperial power. He succeeded.

Like Trump, Roosevelt bypassed Congress to use the powers inherent in the presidency. Executive orders flowed out: for example, to protect forests for future use and create more national parks. The influence of people of great wealth was checked to some degree, though not enough.

Roosevelt railed against trusts and Standard Oil was broken up by the Supreme Court, but the wealthy industrialists continued to be influential. Congress rebelled against his iconoclasm after the midterm elections of 1906 and denied him the money to do many further reforms, including his idea of making his conservation agenda a worldwide movement.

Unqualified to lead a major world power

Unlike Theodore Roosevelt, Trump is probably the least qualified figure to lead a major world power in living memory, in my opinion. In his first term, he was notoriously “difficult to brief on critical national security matters”, according to the New York Times. “He has a short attention span and rarely, if ever, reads intelligence reports, relying instead on conservative media and his friends for information.”

In his 2018 book The Fifth Risk, journalist Michael Lewis showed how much Trump’s hubris and disregard of detail – which was reflected in his first-term transition team – affected his first administration’s ability to be informed about the workings of the US government and prepare to manage risk. “At most of the federal agencies, there were no real briefings,” a former White House official who closely watched the transition process of the first Trump presidency told him. “They were basically for show.”

But who could replace Trump? The US is replete with Republican politicians happy to say yes to Trumpism. They are anxious and ambitious to take control of the MAGA movement in the 2028 presidential contest.

I like to call them Trumpistas, because Trump’s first term as president often seemed to me like the antics of a banana republic’s leader. Today, one thinks of Argentina’s showman president Javier Milei. In Pope Francis’s words, Milei is in the category of “messianic clowns”.

Just as Milei has acted like a crazy showman, Trump played at being an ill-informed expert in his first term. During the unfolding COVID-19 epidemic he acted as a kind of chief medical advisor to the nation, repeatedly advocating non-remedies like hydroxychloroquine, on national television, while the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Anthony Fauci, had to sit near him and endure. Trump appointed many unqualified people to administrative roles and refused to take advice from the presidential transition teams. It was chaos.

So far, Trump’s second time around is only more hectic, more determined, more focused and, I believe, more dangerous in his policies for the world.

Twain was a wise man. He understood we should never expect things to be the same the next time around. Instead, we should seek both the similarities and the differences in any era, to help us make more informed choices about the politicians we elect in the present.

Like the historian who named the first Gilded Age, we should watch for the movement of underlying waves (or trajectories) of power and class within history. The excesses of that era were followed by a reactive wave of progressive reform, from 1900 to 1920. It remains to be seen how Trump’s Gilded Age might rhyme with the first – and what might follow.

Ian Tyrrell had received no funding from any organisation other than five consecutive Australian Research Council Discovery Grants. And no funding at all since 2019.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.