My mother fell in love with my father, Leo, at a Melbourne suburban dance hall in 1946. He was 26, handsome, athletic, smart, a newly minted war veteran, and his grin was infectious. They were a dazzling couple, as their later wedding photos show. Many decades on my mother liked to tell of Leo’s mother warning her that he was going to prove a handful — and was she prepared for this? Possibly my mother told the story to let us know that her love for Leo could never be doubted. Or equally she might have been letting us know that she had no idea what a handful he would actually turn out to be.

In 2017, when Leo died at the age of 97, one of my brothers gave me a folder of papers. They were the documents of our father’s military service. I put them away with clippings, incomplete family trees, photos and birth and marriage certificates that constitute a patchy record of our unwritten family history.

Three years later, at the height of Melbourne’s extended lockdowns against a rising death toll from COVID-19, with time on my hands at home, I began going through the book shelves, throwing out what would never be read or consulted again, and culling papers accumulated through 40 years of writing and teaching. I found forgotten letters from past lovers and exchanges arising from past close friendships in whole series of letters, reminders that once I’d been a young man with hopes and ideals, but no idea what the future held for that young man. There were letters and notes from my father too, one of them dismissing me as a “receiver”. His disappointments in me were many. His letter explained at length what a receiver is on the football field and how team mates feel about such a cowardly player among them.

When I came across his war documents this time it was with a fresh curiosity about the young man who had been the subject of eight years of military clerks’ scribbled notes. I wondered how I might fit this record of him as a young recruit to the violent father I’d known. As his first son and second child I had swum in a world made of him, never wondering whether I really knew him but always feeling I knew him too well. Perhaps, I thought now, in these military records I might glimpse the youth he once was.

Read more: Friday essay: on reckoning with the fact of one's death

****

I can remember a line of white rime along the edge of his mouth as he beat me one night, seemingly unable to stop, my mother from the hallway saying over and over, “That’s enough, Leo.” What strikes me now is that I so neatly filed away this image of his lips during the terror of a beating.

Sometimes there were lucky escapes when he did hold himself back. We had a square wooden table painted blue that fitted in to a kitchen alcove. It was possible to scramble under this table as a small child and press myself against the far wall out of his reach, knowing he would refuse the indignity of getting down on his knees to crawl in after me.

Going through the papers of his war record I began to wonder if he was someone else as a young man — someone I would not have feared and might have even enjoyed knowing.

****

In his late teenage years, wiry Leo was a talented suburban cricketer, about average height, with a thin, straight nose and that handsome grin. His intense green eyes were too deeply set to ever give him an expression of openness, though in certain moods he would have been handsome and irresistible.

A week before turning 19, in the inner northern Melbourne suburb of Carlton, he enlisted in the Australian armed forces, signing an oath to “well and truly serve Australia’s Sovereign Lord the King” for the next three years. This was seven months before Australia joined with Britain in war. Too young for the army, Leo had enlisted in the mostly part-time Citizens Militia Force, a body meant to supply the army with trained recruits; and once war was declared in September 1939, 40,000 were immediately deployed from the militia into full service. Was Leo declaring himself keen to be part of that war once it got under way?

I don’t understand this enthusiasm to be absorbed into the military so early. Perhaps it was a way of putting distance between himself and his childhood family. Or something he did with his mates in a moment of shared restless ratbaggery. It might have been a sign of determination to show his older brothers he had become a man. Among them, Jim and Bernie did not enlist until 1942.

Leo was one of six brothers, and as it turned out he would be the only one among them not to achieve a professional education. Suddenly enlisting at 18 might have been the beginning of a series of impulsive decisions that so complicated his life it became impossible for him to stop improvising as he went, decade after decade, through the rest of the 20th century.

Not once did we hear from him a word of praise for England or the English. With an identity built upon Irish Catholic hatred directed at Great Britain, he could not have joined the military in the hope of being sent to Europe to defend the English.

But even so in November 1941 he signed a new form in Carlton to enlist as a regular soldier. One part he left blank, possibly as self-protection: What is your religious denomination? Control of what he considered personal information was always vital to him.

Less than a year later he signed a further attestation, this time from an office at Adelaide River, a hundred kilometres South of Darwin. He noted on this form that he had been serving as a Corporal at an Australian Army Bulk Issue Petrol and Oil Depot in the Northern Territory. He committed to serving the King “until the cessation of the present time of war and twelve months thereafter”. His Medical Examination Report is a quick handwritten note: “A1”. He left education and religion details blank. He was moved to Darwin.

He had been serving in the Northern Territory since the first week of April in 1942, and by then the Japanese air force had made ten raids on Darwin and across the Territory, including a bombing of Katherine, 300 kilometres inland.

Beginning in June 1942, the bombing raids over Darwin included low-level strafing by Japanese Zeroes. The long-range Zero fighter planes, stripped of armour and radios, were so lightweight, fast and deadly that pilots of the less nimble Australian planes each carried a pocket-map marking food caches buried along the northern coast in case they were shot down — as many were.

Much later my father told us that the troops in Darwin became so familiar with the routines and flight paths of the Japanese bombing fleets that they knew what times were good for being out on patrol or out partying, and when to head for the bunkers near the beach.

There were at least 77 raids over the Northern Territory alone between 1942 and 1944. Nearly 200 Japanese airmen died as their planes were brought down, with many wrecks and bodies still not found today. By my count, my father was present for more than 30 raids during his 11 months in and around Darwin.

In his eighties he became somewhat deaf, and blamed this on the effects of being so close to exploding Japanese bombs. There were stories of him leaving a card game just before a bomb landed, and of raiding the liquor cabinets in abandoned suburban Darwin houses, wheeling out a piano to dance and sing in the empty streets between raids. When he was in his nineties, and I was spending time in Halls Creek, he said that if he had got there during his service in the north it would have been in the back of a military police truck under arrest since Halls Creek was the site of the army’s prison.

My impression is of a restless man moving step by step, oath by oath, deeper into the army, further from home, and closer to harm. He was never the kind of patriot to be proud of dying for his military leaders or his nation but perhaps he was the kind of young man who could not resist an adventure, a chance to prove himself, or a shot at being among the bravest. He could have remained safely a clerk at the Adelaide River Depot, but it seems he was determined to be in Darwin under those bombs.

****

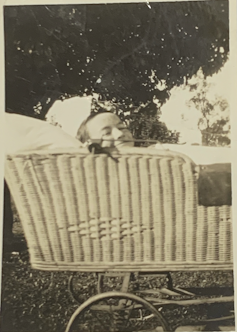

Leo had a younger brother after whom I was named; he was disabled by polio. I have seen a newspaper photo of the older brothers wheeling him on a portable bed to a VFL football game. His illness might have been rare bad luck, but not so rare then that the family felt singled out by a malevolent fate. He died aged 17 in 1940. There is one small, glossy snapshot of him peeking over the top of his wicker pram, head propped by a fluffed pillow, a confident smile across his thin face, his gaze direct. In this photo he looks as if he would take an interest in whoever stopped to talk. He looks well loved.

My father’s parents, Alice and Tom, were stalwart members of their community and their Catholic parish. Alice had been a school teacher. Tom was a local station master in the northern inner Melbourne suburb of Coburg after serving in country towns. He kept a milking cow on Crown land beside his railway station. In a surviving family photo he stands in railway uniform ramrod straight, unsmiling and clear-eyed in front of his extended family. My father never spoke about him except to tell the story of his death.

Tom died at the age of 66, in 1947, fallen from his bicycle in Princes Park on his way home from the Carlton football ground. That afternoon the Carlton team had made a grand comeback in muddy conditions from being five goals adrift of Richmond well into the third quarter. Carlton would go on to win the VFL premiership that year, with their centre-half-back Bert Deacon securing the Brownlow Medal.

When Tom had failed to return, my newly-married father and one of his brothers went out looking through Brunswick and around Princes Park. Eventually they went to the Carlton police station where they were told that there was an unidentified body at the city morgue. The brothers late that night identified the body of their father. He had died of a heart attack.

I wonder about Leo as a 27-year-old identifying the anonymous body of his father only a few years after brothers on both sides of him had died, and himself a recent war survivor.

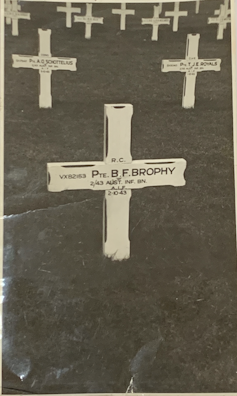

It was the death of the third son, Bernie, early in the battles of Finschhafen on the remote Huon Peninsula in the north of New Guinea that, I think, most deeply shook my father. Bernie died in October 1943 at the age of 26, one of 73 Australians to die in the first of those battles. The record shows my father was given a week’s leave without pay shortly after Bernie’s death, then a second request for another week of leave was rejected. A few months later he changed his “next of kin” notice on his military details from his mother to his father’s name. The telegram notice of Bernie’s death had been delivered directly to his mother, and I guess Leo understood that she could not have withstood another such telegram.

In his last years my father asked to be taken to Papua New Guinea to visit Bernie’s grave at the Lae War Cemetery. No one in the family had been there, and as the last living brother his mind went to this unfinished business. But he weakened too much and too quickly for us to consider the journey.

His other older brother Jim flew bomber planes across Germany from Britain. Afterwards Jim kept his medals out of sight. Refusal to celebrate the war might have been a necessary family gesture of respect for the death of Bernie.

My father’s military mementos lived in the spidery stillness of a dim shed at the back of our childhood yard in Coburg. I remember a jacket with corporal stripes, a sheathed Japanese bayonet that I spent many hours polishing and marvelling over. And a gas mask of rubber and canvas that turned us into monsters as we took turns trying it on.

****

On the eleventh of January 1943, Leo’s papers show he was demoted from Corporal to Private at his own request. He had joined the First Australian Parachute Battalion. Without direct combat experience, and by concealing a defect that would have excluded him, he had managed to be selected for the most elite fighting and flying unit ever formed in Australia. His defect was colour blindness.

His story was that he listened to a man in front answer the questions put on colour vision, memorised them on the spot, and repeated them back to the testing officer. Did he do this for a bet or just for the hell of it? Or was he caught up in some kind of trouble — and this voluntary demotion with a switch to the new paratroop battalion looked to be a way out? And if perception of colour might have meant the difference between life and death on the battlefield for himself and his comrades, why did he risk such disaster? His paths through the army and the war look to me to be erratic, impulsive, risky.

As a member of the First Parachute Battalion, newly Private Leo was being trained to make incursions into enemy territories. As well as airborne drills, the men were expected to learn guerrilla warfare tactics while carrying on their backs equipment weighing up to 30 kilograms. He qualified as a parachutist in December 1943, which meant he had completed at least seven successful jumps over ten months, a time cleaved by the death of his brother Bernie. Refusals to jump were not uncommon among trainees. Most often a refusal to jump occurred on a trainee’s third flight.

The explanation for this was that a first jump could be exhilarating, the second a return to reality, then at the third a man might come to understand the real dangers. These troops jumped without auxiliary parachutes on the reasoning that the auxiliary pack was too cumbersome, and in any case they were jumping at such low heights that if a parachute failed there would be no time to release an auxiliary.

Within the first year of the formation of the Parachute Battalion, five men had died in training mishaps and more had suffered broken limbs, concussion and other injuries. The parachutists soon won rights to extra pay in recognition of risk and danger. These superbly fit and now well-paid young men became infamous for excursions to whatever breweries, hotels and brothels were near their remote bush training grounds.

To be a paratrooper was to know that you might at any time be ordered to jump out into an enemy sky, an easy floating target for snipers.

With one son dead in New Guinea, another training for high-casualty missions, and a third flying bomber planes over Europe, this family must have seemed set to pay much too high a price for any coming Allied victory.

In March, 1944 the Parachute Battalion underwent intensive jungle warfare manoeuvres, participated in dawn attack rehearsals over Wollongong, and were moved from the Blue Mountains to Mareeba in North Queensland not far inland from Cairns in preparation for a possible mission into New Guinea with American support.

It was during this month of feverish preparations for real engagement in the war that my father suffered injuries to his ankles in a jump. He was one of five injured in training jumps during that month. Leo was hospitalised at Concord on the Parramatta River where he was treated then discharged to the Lady Gowrie Convalescent Home. From April until July he was moved between hospital and convalescent home repeatedly. It seemed he was being invalided out of the army.

Somehow, though, and following his own brand of determination, he found his way back to the Parachute Battalion’s training ground in Queensland where he took charge of managing the officers’ mess. J. B. Dunn notes in his history of the paratroopers that at this time Leo had earned the reputation of being “the most tight-lipped man in the Battalion”.

He had made his way back north, I imagine, because he had found for himself a place and a reputation among these paratroopers. Privy to information, accepted by this species of men, and probably at least on the fringes of whatever scams went on, Leo could be trusted to keep the truth close. This fits the man I knew. He loved to talk, and he could have us almost falling off our chairs at the dinner table once he turned his talents to mocking our neighbours and friends. But when it came to business or money or murkier matters of sexuality he was either utterly tight-lipped or so meanderingly impenetrable in anything he said that we could not trust or follow his talk.

Operating from a zone of bluff somewhere between bully and charmer, salesman and commander, he never let up. I expect in business he wore people down. He was always looking to show us he was a man with the inside information, the man with a way through where others floundered. When he wanted one of my younger brothers to be privately tutored in mathematics he found a man a few doors away who was so smart “he could teach a cow to count”.

My brother was sent to him for lessons and I was encouraged to go there too to play chess with this apparently brilliant man. I don’t know why I agreed to go. A deep introvert as teenage years approached, I spent my days when I could with comics and books. Perhaps I went out of curiosity or most likely it was just easier to do what my father told me to do.

This amazing man my father had found lived in a small newly-built house with a young and beautiful wife. When we played chess his beautiful wife would serve us tea and cake, and he would say as she left the room that when he married her he thought he could teach her something, but that she had turned out to be plain dumb. She couldn’t learn anything and he couldn’t teach her anything. Had he made this confession to my father? Shocked that he would let his new, young wife witness him speak these insults, I was distressed. But I returned to the house many times.

I think I kept going back even when my brother’s lessons had ceased. I was half in love with his wife, and I hated him. He was large and pushy, his heavy eyes glistening with self-satisfaction. He liked above all to be able to impress a small boy with his big talk. After a while I thought I understood that in fact my father considered him a fool, and that I must be just as much a fool in my father’s eyes if I sought this man’s company.

****

Perhaps it was some overly-rigid discipline adopted from his military years or an earlier implacable standard he identified with, for when we left to go to school in the mornings it had to be with hair brushed, ties tied, caps and hats straight, and shoes polished. “You might be able to learn Latin but you can’t even learn to polish your shoes,” he would say to me. And in a bloody-minded way I became happy enough to construct a rough version of myself around that accusation. Perhaps the humiliation of it remains as a shadow, a provocation, and a point of pride for me. He held us close but he held us in contempt.

Does his silence about his father (and in fact his whole childhood), and that seeming eagerness to be gone into the army as a teenager, speak of damage done well before he became a soldier in a war? This would be another story, and much of it would have to be fiction.

The one value my father held to as a near-absolute was tribal loyalty. How could it be that we were Catholics (with the moral absolutes that came with that), but no matter how un-Christian or how “sinful” one of us might be, my father’s loyalty to family would come above all? And yet it was inside the family where he let his temper and venom loose. None of it made sense.

His obsession with sexual morality was equally intense. Politicians and public figures were judged on their fidelity in marriage. The increasing public disgrace of the Catholic Church for prolonged and incomprehensible abuse of children in their care confronted him. In the last year of his life my father did try to tell me something about his experience of abuse, perhaps impulsively as a plea for understanding, or more likely to prove some point important and urgent for him at the time. He talked of a family friend who used to visit their home and get drunk and stay the night. He said the man climbed into his childhood bed with him, so he understood what men could do to children. That was all. Perhaps he was showing me the world could teach him little he didn’t already know. He went on to some other topic, some other complaint. He had made his point — about vulnerability, knowledge, men’s evil, and even perhaps about the failure of parents to protect their children in his story that was so brief it was not even a story.

Read more: The Catholic Church is headed for another sex abuse scandal as #NunsToo speak up

****

While working on this essay I have been reading, among a half-dozen other books, Jess Hill’s report on research into domestic abuse, See What You Made Me Do. I realise that my childhood home was sometimes a prison and sometimes a haven. Each day as I returned from school and each morning as I woke in that place I couldn’t be sure which it would turn out to be.

****

My father believed he understood men — a conviction that could bring you forcefully in under his orbit. As long as he could see you as a type, he had you, even if it took him a few wrong guesses to get you right. Then you were pocketed.

His best years were his time in business managing teams of hot-asphalt spreaders. The workers were mostly Italians who loved him and were devoted to him. In my last couple of years at school during the mid 1960s I did labouring work with them through the summer and they told me what a good boss my father was. They bestowed on me some of the affection and loyalty they felt towards him. I was in another world with them, a place where my father was trusted, where something like love passed between him and these men, a place where migrant families saw him as their avenue to success and dignity. I was proud to be the son of such a man — and upset at him for not bringing these qualities into his own family. What happened to him in our presence? What was it that brought out such desperate meanness when he was with us? There was something about family life that could turn him inside-out with rage.

Sometimes, though, he was that generous father we craved and imagined. He could take us into the countryside for hikes and picnics or to the beach in summer where he liked to swim out until he was a far smudge on the sea. For a while there were purple-eyed ferrets caged in the back yard. I remember going ferreting with him and his mates, setting the nets at rabbit-hole entrances across a paddock, then letting a ferret into a burrow and waiting for the rabbits to come racing in a panic up and out and into those nets where they would be easy to grab and have their necks wrung.

Sometimes, though, a ferret would settle with its catch inside a burrow, refusing to emerge. It was then that each person had to guard an entrance while someone began digging down to where the ferret was guarding its kill. It was chaotic, messy, hit-and-miss. But it did put rabbits on our table, and for a while we ate rabbit as often as people eat chicken now. I think it was at this half-wild life of mucking about in the open air with other men, making up the rules as you went, that my father found himself most fully.

****

In January 1945 his extra parachutist pay was cancelled, with a note on his file indicating he was unfit for marching or for long standing due to a “stiff foot”. Nevertheless, in October Leo managed to join a group re-assigned to embark for Singapore. They visited the Changi Prison and contributed a contingent of troops to a guard of honour for the official surrender. Until January 1946 they operated as local Military Police preventing looting while order was restored to Singapore.

Then on May 29, 1946, Private Leo was discharged without ceremony back into civilian life. He had been in the military for most of the first eight years of his early adulthood, and upon resuming his civilian status his home address was still his parents’ address in Coburg.

By September 1949 he would be married with a two-year-old daughter and me, his new baby boy. Seven more children would follow.

How unprepared was this erratic, restless young soldier for the life that he found himself choosing so soon after the war? In her chapter on the experiences of children in families where fathers are abusive, Hill writes of a form of post-traumatic stress suffered by combat veterans:

Every time a potential threat arises a survival response triggers in the brain, motivating the soldier to act defensively — a reaction that can be the difference between life and death.

This describes my father’s reaction when faced with a crisis or even a passing difficulty within the family. He could react as if his physical life depended upon him fighting his way through to an immediate victory — darkly red in the face, veins striking lines down his neck, green eyes alive with an animal urge to survive no matter what damage might be done to others. It was easy to be terrified of him at these times.

Was this reaction fixed in him by the cumulative terrors of the bombing raids over Darwin, the repeatedly suppressed panic he must have faced in jumping from planes, the shock of seeing mates die in accidents, the physical and psychological rigours of training among men renowned for their wildness — and by feelings of grief and guilt over the death of his brother Bernie? He kept a photo of Bernie on his desk all his adult life. How far beyond his temperamental limits might he have been tested during those shaping years of his early twenties? I suspect there was as much shame as pride for him in his war experience, and more confusion than purpose.

Larrikin or patriarch? Trouble-maker or law-giver? Working man or thinker? Tribal lord or obedient Catholic parishioner? Scheming insider or cynical outsider? Husband or knockabout? Survivor or warrior? He loved telling stories, and he was good at it, but some form of confused shame, I think, kept him from telling the stories that were closest to him, which were the ones I wanted to hear.

The almost daily violence at home continued through our childhoods in part because we kept it among ourselves. There I was, silent, arriving at school of a morning shamed by bruised legs; and there were the teachers keeping their distance. The vicious dog our neighbour kept in his tiny yard was no less loud, mad and wrong than my father. But nobody complained about either of them. There might have been no words for what was happening. Now I write what I can in the hope of coming somewhere close to comprehending how my father might have been as a young man bursting with himself while struggling, as I imagine him, between recklessness and fear, cowardice and bravado, all the while desperate to keep himself intact as much as a green young man could in that war-time world. I am writing this with an eye out for the ways my imagined father might point me away from a shamed, inchoate privacy that can only make each of us diminished versions of ourselves.

There is a surviving faded black and white photo of him with a mate who remained a lifelong friend. They are in Darwin on the wharves, both dressed in loose-fitting tropics uniforms, helmets at cocky angles, my father’s arm over his friend’s shoulder as their bodies lean in towards each other.

My father’s expression is easy, open, confident, untroubled. They look like men who have arrived in a place that suits them. This isn’t the man I remember. But it’s a man I’d like to get to know and spend time with. This is the man my mother must have loved so completely just a few years later. In the moment of the photo he appears supremely comfortable with himself and with the kind of friendship made possible in that war zone.

This essay was recently shortlisted for the 2023 Calibre Prize for an outstanding essay.

Kevin John Brophy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.