My father’s father, Joachim Manne, or Chaim, as he was called, was a Galician Jew born in 1872 and raised in Cracow, in the Polish lands of the Habsburg Empire.

His family owned a substantial furniture manufacturing business, The Cracow Furniture Company (KrakowskaFabryka Mebli), whose records go back to 1860. For some reason, unknown to me, Chaim Manne migrated to the United States in 1900. Not long after, he married Leonora Hötchner, his first cousin, which was not uncommon then.

In January 1904 my father was born in New York, always Henry so far as I know, never Heinrich. Chaim Manne failed in business in the Promised Land of America – a surprising fact I like to think helps explain my own almost spectacular lack of commercial acumen – and returned to Europe in 1910, not to Cracow but to Vienna, the capital of the Habsburg Empire.

There he established his own furniture business, in part, it appears, as an agency for the Mannes’ Cracow company and in part as a designer and manufacturer of furniture for individual, wealthy bourgeois clients.

My father was expelled from his school in late 1918 at the age of 14 for a joke that mocked the aged Habsburg emperor, Franz Josef: “The crown (the currency) is no Crown (Emperor).” As a child I learned, as part of family folklore, that from a very early age he ran the Vienna business.

On March 9, 1938, Henry Manne visited Prague to look over the exhibits at the International Sample Fair. Two days later, because of the defiance of the Austrian chancellor, Kurt Schuschnigg, who proposed a plebiscite on the independence of his nation, Hitler ordered German troops to enter Austria, a move forbidden under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. It is well known that the German occupation of Austria was not only unopposed but welcomed joyously.

It is not so well known that the Anschluss, as it was called, unleashed in Vienna, where 90% of the nearly 200,000 Austrian Jews lived, was a violent, vicious and lawless pogrom that historians have characterised as an “open season” on the Jews.

The Times’ correspondent for Central Europe, G.E.R. Gedye, estimated that on the night following the arrival of German troops, between 80,000 and 100,000 Viennese Nazis and pro-Nazi citizens terrorised those who lived in the Jewish quarter, Leopoldstadt.

In the next weeks very many Jews, especially but not exclusively the well-to-do and the Orthodox with their beards and side-locks, were openly and brutally attacked in the streets or in their apartments. This was a pogrom of a kind not seen in Central Europe for centuries and not yet witnessed in Nazi Germany. (Kristallnacht was still almost nine months away.)

As the historian Paul Schatzberg, who was in Vienna and was 12-years-old at the time, puts it: “[I]t was as if a medieval monster had been released from the sewers beneath Vienna.”

Learning of this, my father decided not to return home from Prague.

Humiliation and suicides

The Jews of Vienna had played a disproportionately large role in the professions, the universities and the arts and owned one-quarter of Austrian companies.

According to the Minister of the Economy and Labor, Hans Fischbock, at least 25,000 Jewish businesses in post-Anschluss Austria were temporarily taken over and almost bled dry of their assets by those who were called “the wild commissars”, while 7,000 were forced to close permanently. Shop owners were frequently obliged to paint the word Jude in large, pseudo-Hebraic letters on their front windows as a supposed warning to potential customers.

The homes of many wealthier Jews were entered unlawfully and robbed – of money, jewellery, artworks, furs, clothing and furniture. Even the Reich commissioner appointed by Hitler to oversee the unification of Germany and Austria, Josef Burckel, conceded that “the shining history of National Socialism and the uprising in Austria has been tarnished to a certain extent by the plunder and larceny of the first few weeks”. Hitler eventually issued an order for the lawlessness to stop.

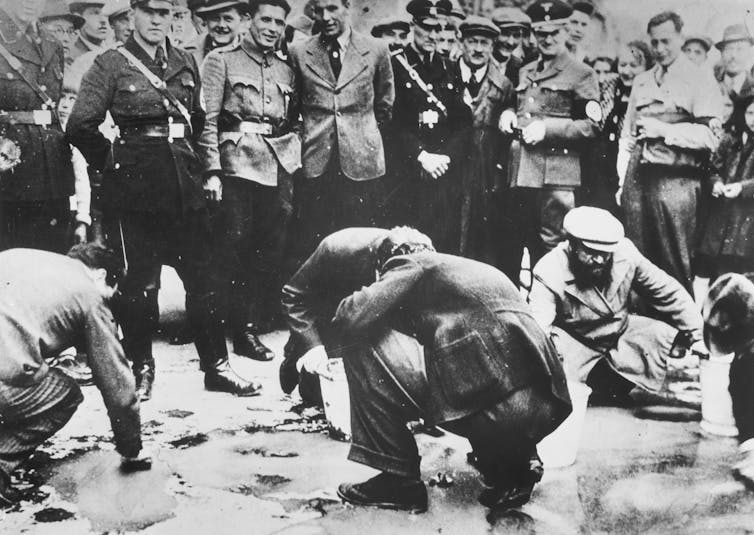

The purpose was not only plunder but also public humiliation. Gedye saw Jewish families forced to “put scrubbing brushes in their hands . . . and made to go down on their knees to scrub away for hours”.

Sometimes they were forced to clean the pavements of pro-Schuschnigg independence slogans with toothbrushes or with buckets of water laced with acid.

Thugs cut off the beards of Orthodox Jewish men or ordered them to cut off their own beards. Synagogues were ransacked and the sacred Torah scrolls burned or torn up. The US consul in Vienna saw several hundred elderly Jews driven onto the Prater parklands and ordered to perform “endless calisthenics” and even to “eat grass”.

Gedye described the demeanour of some Jews after they had been brutalised, as “grey faced, with trembling limbs, eyes staring with horror and mouths that could not keep still”.

Some 60 Jews were arrested and sent to the German concentration camp Dachau. Several thousands more followed in May and June, usually for brief periods before they provided evidence of imminent emigration. Quite suddenly, in this way in the weeks following the Anschluss,the Jews of Vienna learned what it meant to be living in a lawless state without protection from the police.

Contemporary observers were aware that in March 1938 something new and disturbing was taking place in Vienna. In April, after visiting Austria, the British Zionist Leo Lauterbach wrote of the “terrible shock” the Viennese Jews had experienced because of the jeering crowds that

revealed to [the Jews of Vienna] that they lived not only in a fool’s paradise but also in a veritable hell. No one who till then had known the average Viennese would have believed that he could sink to such a level.

The ultimate ambition, he argued with prescience, “may be the complete destruction of Austrian Jewry”.

A fortnight after the Anschluss a member of the US Consulate in Vienna, John C. Wiley, wrote to the White House that “practically all of the Jewish population is in a state of acute anxiety and depression”.

On April 6 he received a letter from an anonymous Viennese Jew, who signed as “one of the unhappy people who went through it personally”, claiming that “hundreds and thousands of suicides occur which are not published in the newspapers”. Thousands might have been an exaggeration; hundreds was certainly not. One careful study estimates that 220 Jewish suicides occurred in Vienna in March 1938. Another that the Jewish suicide figure for the first two months after the Anschluss was 500.

According to Gedye, suicide among the Viennese Jews had become so commonplace that it was openly discussed as an option in a tone that could easily be mistaken for nonchalance. Nor was suicide in Vienna only an individual choice. There were several cases where families decided to die together. In one terrible instance, seven members of a family took poison. One son survived. As soon as he was released from hospital, he hanged himself.

Wiley wrote of another family:

[O]ut of desperation resulting from the savage mistreatment of Jews, a certain Herr Bergman, proprietor of a large furniture store in the Praterstrasse (which had been plundered and taken over) killed himself, his wife, son, daughter in law and grandchild.

To what degree these suicides were driven by fear of violence and humiliation or by despair and the loss of hope, it is impossible to say.

I do not know what happened to my father’s family – Chaim and Leonora Manne and their younger son, Siegmund – in the two months following the Anschluss. Was their furniture business, like that of Herr Bergman, taken over and robbed by some of the “wild commissars” and then closed down? Was their apartment ransacked? Did they witness or experience or merely learn about the street violence?

All I know is that on May 15, 1938, in reality at a time when the ferocity of the Viennese pogrom had died down, the family tried to commit suicide with kitchen gas, and that while Leonora succeeded in taking her own life, both Chaim and Siegmund did not.

My father learned of what happened. In a statement he prepared in 1943 for the Australian government while he was seeking naturalisation, he wrote: “My family in Vienna, consisting of my mother, my father and one brother, Siegmund, attempted suicide in May 1938 in Vienna. My mother died.”

There can be no doubt that the events of May 15 would have been dreadful beyond imagining. I once tried gently to discuss what had happened with Siegmund, my uncle, who arrived in Australia as a migrant in 1946. He could not. My impression was that Uncle Sigi, as I called him, never recovered from what had happened in his parents’ Vienna apartment on May 15, 1938.

Walls closing in

Between May 1938 and December 1939 117,409 Jews emigrated from the Ostmark (German-occupied Austria). At first to emigrate from post-Anschluss Austria – before the Eichmann “conveyor belt” was introduced – Jews had to apply at the central police station in Vienna for a passport; to join queues and fill out many complicated forms from many different government departments; to pay a bewildering series of costly taxes and charges for the privilege of leaving, the “flight tax” for example, before being granted a tax clearance; to obtain an entry visa from a willing government at a time when most doors were closed; and to purchase a ticket on a shipping line if the visa obtained was for a country beyond the European continent.

After their failed suicide attempt, Chaim and Siegmund must have devoted considerable time and money to the task. According to my father’s 1943 statement, by August 1938 they had succeeded. Siegmund had a passport from the German government and, presumably armed with an affidavit from a family member in the US guaranteeing that he would not become a financial burden on the American taxpayer, a treasured US migration visa.

According once more to my father’s statement, on his way to the US Siegmund decided to remain in Britain and, later, to serve in the British Army – according to family folklore, in the same regiment as the famed Central European writer Arthur Koestler. When I was a schoolchild, we were asked to observe a minute’s silence on November 11, the first world war’s Armistice Day. I tried to conjure an image of Uncle Sigi as a soldier. I did not find it easy.

In January 1940 the Jewish community organisation in Austria, the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde, assessed how many Jews still in Vienna were likely candidates for emigration. Of the 54,000 remaining it considered that 24,000 were not because of age, illness or impoverishment. It is almost certain that Chaim Manne belonged to the latter category. Like many elderly Jews – at the time of the Anschluss he was in his mid-sixties – his concern had been the safety of his sons. For the Jews remaining in Vienna the walls were now closing in.

The policies were the same as in the Altreich (Germany before the annexation of Austria) – the bans on free movement; the relinquishing of cars, radios and private telephones; the inadequate food rations; the concentration of the Jews in often squalid semi-ghettoes; the blocked bank accounts; the addition of Jewish identifiers, “Israel” and “Sarah”, to their names; the J stamp in their passports; and the order of September 19, 1941, for a yellow Star of David to be sewn on their clothing.

By the European autumn of 1941 most Viennese Jews had virtually no income or wealth and were living on charity, most importantly that provided by the American Joint Distribution Committee, known as The Joint. This money supported 14 soup kitchens, eight old people’s homes and regular cash payments to 30,000 people.

In October 1941, Jewish policy throughout the expanded Reich changed from enforced emigration to deportation to the East and, ultimately, murder. The first train of the new, general mass deportation left Vienna on October 15, three days earlier than Berlin. This train and each that followed carried almost exactly 1,000 Jews. (The Germans were nothing if not methodical, even “Prussian”, as the stereotype goes.)

Their destinations were either established ghettos, like Lodz and Riga; or the showpiece concentration camp for “privileged” or the elderly or war veterans, Theresienstadt; or newly established killing sites like Sobibor and Maly Trostinec. Auschwitz-Birkenau came a little later.

The Viennese Jewish community’s Kultusgemeinde – the rough equivalent of the Berlin Jews’ Reichsvereinigung – had co-operated with the Gestapo in the enforced emigration policy, even issuing severe warnings to Jews not to try to leave Vienna unlawfully. Now, as a seemingly natural extension of this co-operation, the Jewish leadership of Vienna, like the Jewish leadership in Berlin and indeed throughout the Reich, worked closely with the Gestapo in compiling lists leading not to rescue through emigration but to ghettoisation or murder.

Although they did not know where they were going or why, the Jews remaining in Vienna lived in deepest fear of a deportation order. The correspondence of the Secher family has been published. On October 15, 1941, one member wrote:

It’s that P. [Poland] Action again. You can imagine our anxiety and fear every morning as we await the mail – and what a sigh of relief when it does not bring us that dreaded order.

Maly Trostinec

The Jewish remnant in Vienna was probably now too old, ill-used, fearful and beaten for any organised resistance. Nonetheless a Jewish force of police irregulars, Ordners, was created to ensure full co-operation with the deportation orders.

Jews on the lists were ordered to assemble at a local school on Castellezgasse 35. They were required to surrender the keys to their apartments and their ration cards. The apartments of the deportees were ransacked and remaining valuable possessions removed. As the open trucks drove them to the Aspangrailway station, onlookers often jeered. The trains were loaded from midday to four in the afternoon and departed at seven in the evening.

By October 1942, the month the mass deportation program ended, a leader of the Kultusgemeinde, Dr Josef Loewenherz, reported proudly to his German superiors that 32,721 Viennese Jews had been successfully deported to the East. But to what end? For almost everyone in Vienna, even at this time, a settled policy of systematic and cold-blooded extermination was still beyond belief, unthinkable.

In September 1941 the Germans began the construction of a concentration camp on the grounds of a Soviet kolkhoz,or collective farm, “Karl Marx”, near the Belorussian village of Maly Trostinec, 12 kilometres south-east of Minsk.

According to the order of the chief of the SD and the Security Police, Reinhard Heydrich, the principal purpose of the deportations to Maly Trostinec was death. From May 1942, trains bearing Jews from Vienna, Hamburg, Cologne, Konigsberg and also Theresienstadt arrived at the Minsk goods’ railway station or, later, at a makeshift station closer to Maly Trostinec.

On arrival, they were required to leave their suitcases, money and other valuables, for which they were given receipts. A very small number were selected for work at the concentration camp. The rest were told that they would be settled on estates around Minsk.

These Jews were loaded onto trucks and driven to killing sites, one in the Blagovshchina forest. Here, after the removal of any secreted valuables, they were marched to trenches. As they were killed, music from gramophones and loudspeakers was broadcast to drown out the screams. Almost all the Maly Trostinec victims were shot, although in June 1942 four gas vans were introduced as an auxiliary means of killing.

In total, according to the historian Christian Gerlach, 60,000 killings took place at Maly Trostinec. In total, 9,486 Viennese Jews were transported to Maly Trostinec. Of these, there were nine survivors.

The first transport from Vienna to Minsk left on May 6, 1942, and arrived on May 11 – once more, as in Berlin, in regular third-class passenger carriages, but then from the village of Volkovysk in cattle cars. Eighty-one were selected for work in the Maly Trostinec concentration camp. The remainder were driven to a killing site, stripped to their underwear, ordered to lie face-down in the mass grave that had been prepared for them and shot in the back of the neck.

My paternal grandfather, Chaim Manne – a man who had done no ill to any man or woman – was one of them, murdered because he was a Jew. He was shot in Maly Trostinec in the same week as my maternal grandfather, Otto Meyer, was asphyxiated by carbon monoxide gas in Chelmno.

This is an extract from Robert Manne: a political memoir, published by La Trobe University Press (in conjunction with Black Inc.)

Robert Manne does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.