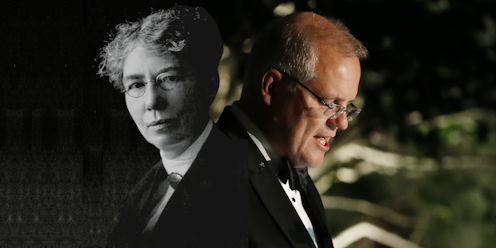

Dame Mary Gilmore died at 97 in late 1962, two and a half years before the birth of her great-great nephew, Scott John Morrison.

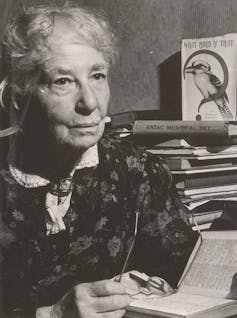

Gilmore was a prolific writer – her collected verse contains 1,437 pages of poetry. She also had a background in radical leftist politics and shared a close friendship with war-time prime minister John Curtin. When he took office in 1941 and told the press “every man should read poetry – for the good of his soul”, Gilmore was ecstatic and a warm correspondence ensued between them.

Gilmore composed verses in Curtin’s honour and proposed a poetry park in the Sydney Botanical Gardens. She saw him as an Abraham Lincoln, a humble, deeply moral man who arose in his nation’s hour of need. When Curtin died in 1945, six weeks before the Japanese surrender, she wrote, “Three words suffice: / ‘He saved Australia.’”

By 2008, when Morrison gave his maiden speech in the House of Representatives, Gilmore’s fame had grown exponentially. In 1984, the electorate of Gilmore was created in Southern NSW, where the sitting member, Labor’s Fiona Phillips, holds an annual Dame Mary Gilmore Oration dinner. In 1993, Gilmore was added to the Australian ten dollar note, along with A.B. “Banjo” Paterson.

Although recently described as a Communist by the PM, Gilmore was not exclusively so. Her politics were shaped by the 1890s generation of Australian radicals whose beliefs were a blend of democratic socialism, unionism, Marxism and pro-labour “agitation”. She campaigned for the Labor Party and supported pioneering female ALP candidates.

Scott Morrison’s Twitter feed shows he has often acknowledged his great-great aunt – Australian poetry’s only Dame of the British Empire – in the face of sneers from both the Left (“She’d be rolling in her grave!”) and the Right (“What, a commie in the family?”).

Speeches come and go, but as a poet and poetry scholar I want to scrutinise the three occasions Morrison has cited Gilmore’s verses on the permanent record in Hansard, in order to evoke a certain version of her and, by extension, himself.

Read more: Book review: Sean Kelly's The Game: A Portrait of Scott Morrison

1. ‘One of her most moving verses’

The Waradgery Tribe (1932) quoted in response to the Apology to the Stolen Generations in February 2008.

Unlike the Bible, the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu and U2’s Bono, Gilmore didn’t feature in Morrison’s maiden speech as the new Liberal MLA for Cook on 14 February 2008. However, in his response to then PM Kevin Rudd’s Apology to the Stolen Generations, Morrison quoted a Gilmore poem in full in the House of Representatives just four days later.

Rising to support this motion, he said:

… My first real contact with our first Australians took place almost 30 years ago on a property called Greenwood, which is around 30 kilometres east of Cloncurry in Central Queensland … This was the family property of my Uncle Bill, the grandson of Australia’s grand old lady of letters, Dame Mary Gilmore, whom I know as Great-Aunt Mary.

There is much that Aunt Mary and I would probably disagree on today and I am sure, based on my father’s reports of his regular visits to her little flat in Kings Cross when he was a young policeman on the beat, she would be more than up for the discussion. However, one thing I know we would not disagree on is the need to address the disadvantage of our Indigenous communities … I wish to pay tribute to her efforts on behalf of the Indigenous people of this country by reading from one of her most moving verses, The Waradgery Tribe:

Harried we were, and spent,

Broken and falling,

Ere [before] as the cranes we went,

Crying and calling.

Summer shall see the bird

Backward returning;

Never shall there be heard,

Those, who went yearning.

Emptied of us the land;

Ghostly our going;

Fallen, like spears the hand

Dropped in the throwing.

We are the lost who went,

Like the birds, crying;

Hunted, lonely, and spent

Broken and dying.

In this speech, Morrison reflects on how he and his brother were impressed by Aboriginal stockmen at Greenwood. He calls the Apology an “act of grace”, but maintains, “I do not seek to say sorry on behalf of our past generations. I have no right to do that”. He goes on to cite two novels by white authors, Kate Grenville’s The Secret River and Andrew McGahan’s The White Earth, as examples of how to confront the past “without judgement”.

Sincere Scott (it’s the right thing to do) overlaps here with Hedging Scott (but we can’t judge the past), Farming Family Scott and Sort-of-Literary Scott. The last can’t seem to find a single Wiradjuri or Indigenous author to read (even in 2008!). Nor does he manage to distinguish historical fiction from written or oral history.

The Waradgery Tribe is a prime example of the well-worn, romanticised and misinforming “last of their tribe” literary trope. The poem appeared in Gilmore’s 1932 collection Under the Wilgas, set in south-western NSW, where she was born and educated. Across the collection, she acknowledges (and appropriates) Wiradjuri presence, but she also goes further. The Hunter of the Black, her poem about a genocidal mercenary who later becomes a respectable town mayor was, Gilmore insisted, based on true events.

Sincere though his spoken tone is, Morrison’s citing of the poem in support of an apology to the Stolen Generations seems tone deaf given the poem itself is quite offensive (and out of step with 21st-century Wiradjuri reality) with its references to a “lost” people who are “broken and dying”.

Read more: The Secret River, silences and our nation's history

2. ‘Above all of that, she was a wife, a mother’

No Foe Shall Gather Our Harvest (1940) quoted for the 50th anniversary of Gilmore’s death in November 2012.

Morrison was more expansive on 29 November 2012, when as Shadow Minister for Immigration, he rose to mark the 50th anniversary of Dame Mary’s death. Gilmore was now “a trail-blazer”, “a passionate nationalist, a zealous activist, an advocate for workers’ rights rather than union largesse” who spoke for “the voiceless – women, children and Indigenous Australians”.

Morrison offered some rare biographical detail in this speech, noting Gilmore had joined the “hopelessly failed settlement experiment” of the New Australia Movement in Paraguay, where she married the shearer William Gilmore. There was no mention of the fact that they were utopian socialists and the “settlement” a commune.

Details about Gilmore’s literary career were given, including her support for literary journals. One of her eight poetry collections was named (1918’s A Passionate Heart) and a single poem from it (Gallipoli).

In this 2012 address, Morrison lauded Gilmore as a patriarchy-busting role model for “our young women”, even if the word “feminist” remained as unspoken at this point as “communist”. His daughters, he announced, “look on the $10 note with great pride”. After dropping his trademark caveat (she may well not agree with everything I agree with today) Morrison concluded by reading Gilmore’s poem No Foe Shall Gather Our Harvest, which appears on the note:

Dame Mary wrote:

We are the sons of Australia,

of the men who fashioned the land;

We are the sons of the women

Who walked with them hand in hand;

And we swear by the dead who bore us,

By the heroes who blazed the trail,

No foe shall gather our harvest,

Or sit on our stockyard rail.

Dame Mary, was, he said, “a remarkable woman of who[m] we are deeply proud”. Yet Hedging Scott, while lauding the Dame’s achievements, had also said earlier, “But, above all of that, she was a wife, a mother and, maybe to the surprise of those on the other side of the chamber, my great great aunt.”

But above all of that? To me, this foreshadows the later clash of his homespun “family values” with contemporary feminist advocacy. It also belies a more complicated reality.

Gilmore lived in Sydney from 1912, over 2000 kilometres from her husband William. Their son (also William) later joined his father at the Cloncurry farm and the family were only reunited on rare visits to Sydney. After father and son both died on the farm in 1945, Gilmore resolved to be buried with them.

On a tour of rural Queensland after his 2019 election “miracle”, Morrison stopped by Gilmore’s grave. He felt politically impervious enough to finally say: “She was a communist – I’m not kidding.”

Months later, in September 2019, President Donald Trump took to the stage at the White House Rose Garden to officially welcome the visiting Aussie PM. Trump unexpectedly launched into the same eight lines of No Foe Shall Gather Our Harvest, noting Morrison’s familial link to this “acclaimed Australian author” and raising a glass to “a very, very special people … and country”.

Taking his turn at the podium, Morrison gushed: “Well, he got me. Dame Mary, my great great aunt, would be very, very proud.”

He later told reporters he became “a bit weepy” during Trump’s recital of “Aunt Mary’s poem” because it was “the sort of detail that shows an affection”.

Did President Trump know about Aunt Mary’s red credentials? We don’t know, but Trump carefully recited what he called “beautiful” Australian leftist poetry, hailing it “an inspiration to patriots everywhere”.

3. ‘This is the day of men [and women] greater than kings’

Edmondson V.C. (1941), quoted for the centenary of Anzac on 24 June 2015.

Gilmore the war poet was invoked again to mark the centenary of Anzac. By this stage, Morrison had moved up in the Abbott Government from Immigration Minister to Social Services Minister. In June 2015, we glimpse, in Hansard, Morrison reciting Edmondson V.C., which honours Australia’s first WWII Victoria Cross recipient:

Let the kings pass, and shallow pomp retreat,

This is the day of men greater than kings!

For them the drums of time shall ever beat,

And at their tomb death stands with fallen wings.

Though in the eyes of grief may brim the tears,

Above grief stands a pride tears cannot drown.

Morrison remarked that he had also recited these lines at the Anzac Day dawn service at Cronulla that year. He ended his speech with a Gallipoli-themed poem by a Year 6 student from his electorate of whom “my [great] great Aunt would be very proud”.

Over time, Edmondson V.C. has become Morrison’s go-to Anzac poem. At the 2019 Townsville Anzac Day dawn service, his first as Prime Minister, he expanded his repertoire to four whole stanzas of the eight-stanza original, tweaking a few lines as he went because “she wouldn’t mind me updating it”, and posted the video to his social media.

Morrison’s tweaks were especially glaring at the start, where “Let the kings pass, and shallow pomp retreat, / This is the day of men greater than Kings!” was altered to “This is the day of men greater, / and women greater than Kings and Queens.”

The arrayed troops at Townsville could have their pomp - and some gender balance too.

The doctored lines read awkwardly. But there is little available evidence that the PM is a poetry fan. Rather, he appears to be a (selective) Gilmore fan. (At both the 2018 and 2019 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards, Morrison invoked his relationship to Gilmore as evidence of a literary pedigree.)

It’s unlikely, however, he will expand his Gilmore repertoire to include poems like The Hunter of the Black, Fourteen Men (on colonial violence against Chinese migrants), I Wisht I was Unwed Again, or The Koala: A Plea for the Slaughtered.

Read more: Explainer: poetic metre

Farming Family Scott, meanwhile, is happy to promote the Cloncurry Prize “Spirit of the Outback” poetry competition created in Gilmore’s honour, and Sincere Scott beams as he reads a poem written by his daughter Lily for Australia Day. Yet, Hedging Scott’s government has been miserly with funding for pandemic-stricken writers, artists, publishing houses and universities.

John Curtin, by contrast, espoused an interconnected vision of an intellectual nation, which, as he stressed in a 1942 speech for Gilmore’s 77th birthday, actively valued writers, poets, thinkers, artists, dreamers, sculptors and musicians.

To anyone inclined to question this, Curtin’s reply was plain. Without them, he declared in the darkest depths of World War II, “this country would be but a material place, well fed, perhaps, but not happy or enduring”.

I am a direct relative (great-grandson) of Labor PM John Curtin, but not politically affiliated. My book Good for the Soul: John Curtin's Life with Poetry goes into this relationship in more detail.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.