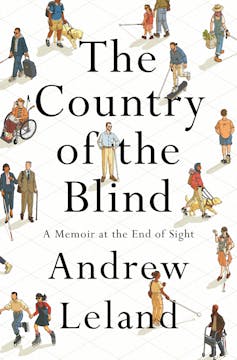

Andrew Leland was in his thirties when he had to stop driving at night – and then stop driving at all. Next, he had to start using a cane in public. As the cycle of decreasing vision became familiar, each absent sliver of vision required more adjustment to how he navigated the world.

He moves through the same steps in the same sequence each time, but each loss is unique, and uniquely stressful. And he can still see the disdain of sighted people, which makes him long to lose all his vision at once:

I thought about my periodic desire for the eye disease to just get it over with, and take the rest of my sight. I wanted to be relieved of seeing the way people look at blindness: the scorn, the condescension, the entitled, almost sexual leer. Skepticism, pity, revulsion, curiosity. I know I’ve looked at blind people this way too […] But I was a different person then: I didn’t really think of myself as blind.

Blindness, creativity and memoir

Responding to the idea that James Joyce’s blindness influenced his writing of Finnegans Wake, his biographer Richard Ellmann asserted:

The theory that Joyce wrote his book for the ear because he could not see is not only an insult to the creative imagination, but an error of fact. Joyce could see; to be for periods half-blind is not at all the same thing as to be permanently blind.

What Ellmann presents as a fact is actually a common myth. 85% of permanently blind people have sight. (I am one of the 15% of blind people who is totally blind, and the even smaller minority born this way.) And the line between blind and sighted is not straightforward. The results of a number of tests, and other factors, are taken into account.

Ellmann sounds like he is uncomfortable with thinking of Joyce as blind, and thinking of blind people as creative.

By contrast, during the writing of Finnegans Wake, Joyce himself was relaxed about the losses and gains of his situation. Responding to a letter from a friend on this topic, he wrote: “What the eyes bring is nothing. I have a hundred worlds to create, I am losing only one of them.”

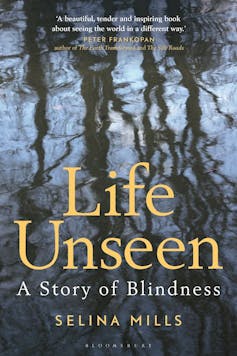

Review: The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight – Andrew Leland (Penguin Press), Life Unseen: A Story of Blindness – Selina Mills (Bloomsbury Academic)

These tensions of identity and creativity between those who are sighted and those who are blind existed long before Joyce, and are still prevalent a century later. They are explored with candour and thoughtfulness in two recent memoirs, by Selina Mills and Leland.

Like Joyce, their versions of blindness mean they have sight that gradually decreases over decades. And they are writers – both are journalists.

While their memoirs are obviously written from personal vantage points, Mills and Leland detail much more than their own stories. Interwoven with their experiences of becoming blind are the experiences of blind writers, performers, teachers, activists, inventors and so on.

Mills, who is from the UK, researched blind women throughout European history. The few famous blind women she mentions are from outside Europe (which demonstrates the need for her research). One of them is American activist and author Helen Keller (1880-1968). Another is Tilly Aston (1873-1947), also known as “Australia’s blind poet.”

As Mills’ own sight decreased, she felt surrounded by sighted people’s stereotypes of blindness. She was compelled to research the real members of her community, for herself and her readers. As she writes:

so much of our knowledge of blind people has relied on how sighted people have interpreted blindness. […] We fear it, we punish with it, we find it powerful and alluring all at the same moment and have done so for centuries. Principally, we rarely hear the voices of blind people themselves. Why not? Who were these blind people who lived and died, who were not just heroes or burdens of the sighted world?

Similarly Leland, who lives in the US, concentrates on the recent and present US blind community in order to encourage both himself and his audience to develop a more nuanced understanding of what it means to be blind:

I met people who said that their blindness meant nothing to them – that it was a mere attribute, like hair color – and others whose blindness utterly defined and upended their lives. […] I sympathized with all of these positions, even as I wondered which attitudes I would adopt for my own life. I tried to understand how blindness was changing my identity as a reader and a writer, as a husband and a father, as a citizen and an otherwise privileged white guy.

Read more: The amateur’s age of unriddling: Finnegans Wake on stage

What blind people have in common

I was drawn to both books by their exploration of historical and philosophical questions. But as I read, Leland and Mills’ experiences of being blind with some sight also became compelling for how universal they are.

I have talked with many people losing sight as they transition to blindness, and am well aware of the shape of the sight-loss journey. Yet these books emphasised to me the significant number of experiences blind people have in common, regardless of how much sight we have, or where we live, or when we were born.

Mills and Leland have both been losing sight for two decades now. But they began at different levels of sight and the cause was different for each of them.

Leland’s sight loss began as night blindness when he was a teenager. His research on the early internet suggested the cause was retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a degenerative condition where night blindness is followed by peripheral vision loss, then central vision loss, sometimes ending in total blindness. After his first year of college, he went to an eye clinic where his self-diagnosis was confirmed.

Read more: Happy birthday, Braille: how writing you can touch is still helping blind people to read and learn

Leland’s interest in understanding blindness as an identity develops another dimension when he learns his retinitis pigmentosa is part of his Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. He discovers that throughout history, blind people and Jewish people were often denigrated in similar ways.

Medieval literature and disability studies researcher Edward Wheatley points out, for example, that both groups were branded as greedy, lazy, and dishonest. And both groups were said to be responsible for their marginalisation by Christian society – Jewish people for refusing to convert, and blind people for sinfulness.

Significantly, both blind people and Jewish people were early and constant victims of the Nazis. And the threat multiplied if you belonged to both groups.

The borderlands between blind and sighted

Mills’ sight began to decrease in her early thirties. However, she was already accustomed to living in the borderlands between blind and sighted: she was born with no sight in one eye.

Growing up, she attended mainstream schools. Her childhood, though, had many experiences in common with other blind children. Teachers incorrectly assumed that she had learning difficulties when she was six and she got a prosthetic eye when she was ten. She was left to drift rather than being supported throughout her schooling and she finished school without having been taught braille or how to use a cane.

Having only spent time with sighted people, she was used to thinking of herself as similar to them, even though she was often exhausted and they were not.

In her twenties, she became a journalist and travelled throughout Europe. She only sometimes carried a cane, just as a precaution. Mills was in her early thirties when bus numbers and step edges became difficult to see. This prompted her to go to an ophthalmologist, who discovered she had an inoperable cataract.

Other people’s prejudice

Mills and Leland have to manage a range of emotions that accompany losing sight, as well as the reactions of their families and friends. But the most difficult aspect of being blind, they discover, is other people’s prejudice.

Echoing the experiences of the blind people whose lives they explore, they are exhausted by the frequency and variety of prejudice they have to manage in their daily lives.

Sometimes it is overt: being denied education or work, being told to not have sex or have children, being refused entry to a venue if not accompanied by a sighted person. Sometimes it is questions disguised as concern – about whether you can cook, or how you are sure you have performed a work task properly, or whether you actually need to learn braille.

It always contains the message that being sighted is superior to being blind, and blind people should feel envious of sighted people and ashamed of who we are.

I suspect it was this prejudice Joyce was reacting to when he said, “What the eyes bring is nothing.” I don’t think he meant he had no use at all for the tiny amount of sight he had. I think he was exasperated by so many people continuing to insist it must be more difficult for him to write as a blind person. Certainly, he felt sight was not a prerequisite for creativity and that blindness had enhanced his writing.

This prejudice even extends to sighted people believing they have the knowledge to distinguish between blind and sighted strangers within seconds of seeing them. And they believe they are entitled to call out anyone they are convinced is faking it.

This happens to Mills at a train ticket barrier when the guard asks her for her ticket, then for her disabled person’s travel card. Like most blind people, she keeps the card in a specific place in her wallet, ready for these occasions. But the guard associates blindness with slowness and incompetence, so takes her organisation as evidence she is faking blindness:

“How did you get that then?” “Get what?” “Your disability travel card? – I mean, you can see all right, can’t you?” Having learnt to be patient with other non-believers, I was calm. “Oh, I know, but I have only got about 20 per cent vision on a good day. The doctors tested me.” Unconvinced, the guard continued: “You think you can get your card, and just get away with it. I saw you walking down the platform, bright and breezy. You are faking it!” He was quite proud of his little diatribe and seemed unkeen to let me through unless I confessed to my high crimes and misdemeanours.

Fortunately she has an irrefutable piece of evidence – her prosthetic eye, which she removes and presents to the guard:

“ The queue gasped. I was shaking with fury. You really think I had my real eye plucked out and went through the pain of having a false eye made, just to get a discount on my f*king train ticket?

Blind people are harassed in this way regardless of our level of sight. As a totally blind person, I have many similar anecdotes. However, these experiences can have a particularly devastating effect on someone adjusting to blindness.

Both Mills and Leland discuss how incidents like this make them reluctant to use a cane. "Sometimes I left the cane behind, just to have a day off from the reactions, but the falling over and bashing into lampposts is not always worth it,” writes Mills. “The more I need to use my cane to find curbs and doorways, the more patronizing and intrusive (and sometimes hostile) strangers become,” echoes Leland.

Blind women from history

Connecting with other blind people helps both Leland and Mills not just accept, but value their blindness. The blind people they encounter show them how to minimise the effect of sighted prejudice on their identity, and to understand that being blind is inherently creative.

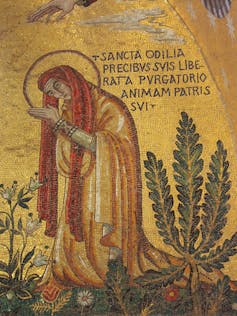

Mills connects with blind women from history who deserve to be better known. And it is thrilling to learn about them with her, and to know that details of their lives are finally more publicly accessible.

They include Saint Odile of Alsace (an area now occupied by France and Germany), born in 660 AD, who travelled throughout Europe and founded two monasteries. Therese-Adele Husson, born in 1803, was a French writer of children’s books and romantic fiction. And Maria Theresia von Paradis, born in 1759 in Austria, was a talented pianist from a young age.

As an adult, Maria Theresia’s life was divided between being subjected to one horrific so-called cure after another and performing throughout Europe. She was friends with Haydn, as well as Mozart – who composed a piano concerto for her. She was a composer herself, of more than five operas and more than 30 sonatas, and in Vienna she established one of the first schools for blind musicians.

As Mills points out, “unlike Mozart and Haydn and a few other known women composers, who died penniless or unpublished, she had what few musicians had in the age – a successful profession and an income.”

Developing a blind identity

Leland feels connected to a number of 20th-century blind writers, such as James Joyce, and to many current blind writers, as well as advocates, engineers and artists.

Many blind people devoted years of their lives to argue for the rights of all disabled people to have equal access to public spaces, education, employment and more.

Meanwhile, so much technology in everyday use over the last century has been created or enhanced by blind people, from long-play records to internet chat forums. And every step of the way, many blind people generously shared their knowledge to help others who were still developing their skills.

One of the people who shared their knowledge with Leland was American activist and teacher Barbara Loos. Leland met Loos at a blindness convention. She encouraged him to attend the residential training course that later accelerates Leland’s cane skills and confidence.

She then pinpoints the problems with how he’d been taught to read braille. This sets him on the path to reestablishing and reinvigorating his identity as a reader by learning to read braille correctly and obtaining a braille display – a device that connects to a computer and displays the screen one line at a time.

once I’d finished my last course, I brought it [the braille display] out again, and fell in love. Reading on the braille display was a palliative against my anxiety about going blind. The more facility I gained with it, the more I could imagine a rich life for myself as a blind reader.

Reading these books, and the lives and work they explore, I feel extremely proud of my community.

Amanda Tink does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.