Rates of mental ill health among young people are on the rise. Between the years 2020 and 2022, 39% of Australians aged 16 to 24 had a mental disorder in the previous year, compared to 26% in that age range in 2007, and 27% of those aged 18–24 in 1997.

The recent Lancet Psychiatry commission on youth mental health documents equally steep increases in mental illness in the United States, UK and Denmark. Governments, mental health services, educational institutions and parents are struggling to respond. But what is behind these trends?

Two accounts seem to be emerging. According to one, which I’ll call the “cruel world” narrative, young people are distressed because the world is in bad shape and getting worse.

Facing climate emergency, unaffordable housing, precarious employment, rising inequality and other dire mega-trends, they are canaries in a societal coalmine. By this account, the mental health crisis is the direct result of systemic adversity.

The alternative, which I’ll call the “cultural trend” narrative, is a little less bleak. Young people are experiencing more mental illness not primarily because the world is grim and getting grimmer, but because cultural shifts have shaped how they perceive and inhabit it.

This narrative suggests a culture preoccupied with harm creates vulnerability and leads people to view life problems through a psychiatric lens. Adversity and social dislocation undoubtedly contribute to young people’s distress, but the way therapeutic culture frames their suffering makes it worse.

The two narratives offer different prescriptions.

From the “cruel world” perspective, the ultimate causes of the mental health crisis are the basic structures of our society, economy and ecology. Only systemic, macro-level changes can arrest them.

For proponents of the “cultural trend” narrative, the focus of intervention is more micro. We should challenge the social practices and technologies that create vulnerability and undermine mental health.

As a social psychologist, I take it as self-evident that adverse social environments play a leading role in the creation of mental ill health: that we can’t isolate human misery from its broader context. However, I’m equally certain that culture plays a crucial part.

A range of cultural changes that could plausibly undermine mental health are well underway: increased immersion in the digital world, rising political polarisation and preoccupation with risk and harm, among others. Separating them from the tangled skein of factors that contribute to the youth mental health crisis is a matter of urgency.

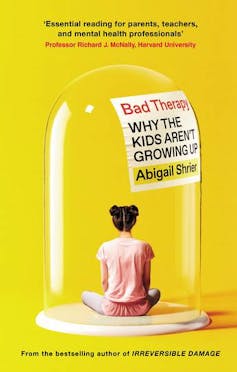

Abigail Shrier’s new book Bad Therapy, a forceful exposition of the “cultural trend” narrative, provides a golden opportunity to explore some of them.

Youth mental health and the culture wars

Journalist and cultural critic Soraya Chemaly’s recent book The Resilience Myth exemplifies the first narrative. Young people are distressed “because the world is distressing, and adults have failed them”. Their sensitivity and emotional honesty place them at higher risk of distress than their elders, and the ubiquity of trauma, oppression and existential climate threat tip that risk into illness.

Chemaly’s solutions lean towards the revolutionary. Her targets include individualism, rigid gender ideologies, capitalism and white supremacy.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation presents a version of the second narrative. Haidt does not deny the magnitude of the challenges young people face. However, he questions whether their rising rates of mental ill health directly follow increases in adversity.

This inflection point in the trajectory of young people’s mental ill health appears to have occurred in the early 2010s. However, many of the systemic trends now held responsible for the crisis – like climate change and rising income inequality – have been building over a much longer period, when rates of ill health were relatively stable. By implication, the precipitating causes must be more specific, recent developments.

Haidt identifies two such changes: the advent of smartphones and “safetyism”. His focus on smartphones has been widely reported. But his equally important emphasis on the cultural preoccupation with protecting us from harm has received less attention.

Haidt argues that parental and institutional over-protection hampers the development of young people’s resilience and autonomy. Citing the idea of “anti-fragility” he proposes that risk, challenge and failure are required to build strength.

By now, it should be obvious that the youth mental health crisis has become politicised, sucked into the vortex of the culture wars.

The crisis can be attributed either to an uncaring system that oppresses the most vulnerable, or to emerging social trends that do young minds no favours. It can be addressed either by progressive social change, such as economic redistribution and environmental protection, or by winding back some damaging cultural developments, such as promoting unsupervised play for children and restricting access to smartphones in schools.

Blaming ‘bad therapy’

Whereas Haidt spends much of his book on the damage done by young people’s immersion in the digital world, in Bad Therapy, Shrier castigates mental health experts for contributing to the crisis they claim to be addressing.

Shrier is a controversial figure. Her previous book Irreversible Damage drew protests and bans for critiquing youth gender medicine and arguing that social contagion plays a role in the rise of girls seeking gender transition.

The former lawyer and Wall Street Journal columnist, who has not previously written at length on mental health, is just as fierce in prosecuting the case against the growing influence of mental health expertise.

Bad Therapy begins by arguing that the rise in mental ill health among young people is not merely a response to deepening life challenges. Instead, Shrier writes, it is driven by destructive cultural shifts and misguided experts. She suggests many people who are experiencing ordinary problems in living have been led to believe their unhappiness is psychiatric in nature.

Shrier is quick to clarify that distress often is genuinely severe. There are “two distinct groups of young people”, she argues: those experiencing “profound mental illness” and “the worriers; the fearful; the lonely, lost, and sad”.

This second group is Shrier’s battleground. These “worriers” have fallen victim to shifts in education and parenting, and to the expansionism of the mental health field. On this point, she doesn’t mince her words. “No industry refuses the prospect of exponential growth,” she writes, and “the mental health industry is minting patients faster than it can cure them.” As a result, “we rush to remedy a misdiagnosed condition with the wrong sort of cure”.

Shrier challenges the common view that mental health interventions – therapy for short – are invariably beneficial. She reviews evidence suggesting therapy is less helpful than it is touted to be, and that it can sometimes be actively harmful. For instance, “psychological debriefing” immediately after exposure to traumas can interfere with recovery.

Mental health treatment can undermine recovery, she suggests, by “hijack[ing] our normal processes of resilience” and creating dependency on professionals. It can crystallise illness by applying diagnostic labels too liberally.

Diagnoses may bring relief to anxious and desperate parents, but they can also affect how their children perceive themselves and are perceived by others. Much like therapeutic staples such as trauma and chemical imbalance, diagnostic terms can convey the view that young people are fundamentally damaged and have little control over their predicaments.

Many of these critiques of therapy chime with familiar attacks on medicalisation. But Shrier also advances some newer criticisms. Mental health treatment can induce rumination and a passive focus on feelings: common features of anxiety and depression. “Bad therapy encourages hyperfocus on one’s emotional states, which in turn makes symptoms worse.”

Therapy can also affirm young people’s worries and encourage public sharing of distress in ways that can entrench unhelpful patterns. “A dose of repression,” Shrier counters, “appears to be a fairly useful psychological tool for getting on with life.”

Mental health workers overlook the possibility that talk therapy can have these adverse consequences, Shrier argues – although it is no less plausible that some psychological treatments may do harm than that some medications can have adverse side effects. Without questioning therapists’ desire to help, she takes the hardheaded view that they have incentives not to acknowledge the harm they may be causing.

Should teachers be delivering therapy?

The clear implication of Shrier’s argument is that we should challenge, rather than expand, therapeutic approaches to young people’s mental health. Instead, she finds that American schools are riddled with bad therapy, often under the banner of “social-emotional learning”.

Shrier maintains that social-emotional learning licenses psychologically untrained teachers to work in a therapeutic mode. It encourages excessive self-focus, demands emotional disclosure and can expose children to dual relationships, all out of view of their parents.

Social-emotional learning and related elements of therapeutic schooling don’t just encourage unhelpful inwardness, she argues. She contends they also use questionable teaching methods and draw time and energy away from academic learning.

Of one effort to smuggle emotional learning into a maths class, Shrier writes: “I began to wonder whether this wasn’t some sort of ploy by the Chinese Communist Party to obliterate American mathematical competence.” She concludes that

social-emotional learning turns out to be a lot like the Holy Roman Empire. Neither social, nor good for emotional health, nor something that can be learned.

Schools’ therapeutic missions also undermine how they educate disadvantaged students. Shrier contends that some “trauma-informed” practice prejudges students who have experienced hardship as fragile and in need of blanket mental health interventions, while lowering expectations for their behaviour and academic achievement. Meanwhile, classroom chaos is created by excessive accommodation of disruptive students.

Shrier takes aim at the outsized role “trauma” plays in currently popular accounts of mental ill health. She reserves some of her sharpest criticism for psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk, whose bestselling book, The Body Keeps the Score, places trauma front and centre in mental ill health, and physician Gabriel Maté, who claims trauma contributes to everything from cancer to ADHD.

Seeing childhood trauma as the buried root of most adult mental health problems conflicts with copious evidence that resilience is the normal response to adversity – and that trauma memories tend to be recalled accurately, rather than locked voiceless in the body. Shrier maintains that the concept of trauma has become trivialised through over-use. She chastises experts for characterising problems ranging from anger outbursts to procrastination as trauma responses.

In the school environment, the consequences of elevating trauma are troubling:

under the banner of “whole child” education and “trauma-informed” care, educators greet every child with the emotional analogue of a gurney, all but begging kids to hop in. They never wait to see who might be injured because every child is encouraged to see herself as overtaxed and worn out. They encourage every child, constantly, to think about herself and her struggles.

Against ‘gentle’ parenting and ‘overmanaged’ kids

Shrier condemns schools for usurping parental authority, but argues that contemporary parenting also subverts itself.

“Gentle” styles of child-rearing end up creating anxious, unresilient children whose demands are endlessly accommodated and whose dependency is reinforced. A strange combination of permissiveness and over-involvement makes for exhausted parents who are unwilling to exercise adult authority or to impose consequences on behaviour, she argues.

Liberal American parents may look askance at earlier styles of parenting, but by placing emotional wellness front and centre in their relationships with their children, they are making their task harder and more thankless.

As Shrier observes:

forty-year-old parents – accomplished, brilliant, and blessed with a spouse – treat the raising of kids like a calculus problem that was put to them in the dead of night: Get it right or I pull this trigger.

Ultimately, the failures of therapeutic parenting are another strike against the mental health experts who advocated for it. Shrier urges parents to cut themselves loose from the advice of parenting sages, for the good of their children: “love means occasionally telling an expert to get lost”.

Concretely, parents should step back, stop compulsively monitoring and over-praising their children, reduce scheduled activities, enforce consequences and encourage independent behaviour. She writes: “if you could do something at their age, let them give it a whirl”.

A parent’s goal should be to set their children free from an “overmanaged, veal-calf life” and ensure they experience “all of the pains of adulthood, in smaller doses, so that they build up immunity to the poison of heartache and loss”.

Not all therapy is bad therapy

Bad Therapy is an unashamedly polemical book. Shrier has strong views on what is wrong with the culture of mental health in the US – and takes these supposed failings as examples of broader progressive trends she opposes.

The mental health crisis troubles her not only for its human costs, but because it erodes key conservative values: self-reliance, strength, parental authority and freedom from institutional compulsion.

Shrier’s rhetoric is sharp-elbowed, with a memorable turn of phrase. Some villains are identified and savaged, though the criticised cabal of mental health experts is often a faceless mass. The book is studded with revealing case studies and she interviews many leading scientists, like Paul Bloom, author of Against Empathy, memory expert Elizabeth Loftus, leading trauma psychologist Richard McNally, and generational difference researcher Jean Twenge.

Though she presents herself as defending science against ideology, at times Shrier’s claims run ahead of the data. There is little evidence that mental health interventions are creating ill health on a large scale, for example, or that increases in self-diagnosis among young people account for increases in their levels of distress.

Some schools may implement socio-emotional learning in problematic ways. But studies typically find that they benefit academic achievement. And though there is evidence that today’s young adults are reaching some developmental milestones later than earlier generations, there is little direct evidence that gentle parenting is responsible for the delays.

Shrier tends to present the mental health world as a monolith. But anyone working in it knows it to be criss-crossed with divisions: between researchers and practitioners, consumers and professionals, medical and non-medical workers, and numerous disciplines and therapeutic tribes.

The idea that this Babel of voices is united in a process of crisis creation is hard to credit. Not all therapy is bad therapy. Indeed, many of the positions Shrier espouses – for facing challenges head on and experiencing the consequences of our behaviour, and against safetyism, over-medication and the therapeutic excavation of our childhoods – are gospel for mainstream cognitive behaviour therapists.

Correcting concerning trends

Even so, for all its exaggerations and simplifications, Bad Therapy is a timely corrective to some real and concerning trends. It is increasingly clear that over-diagnosis of mental illness is common, especially among young people, and that diagnostic labelling can have adverse implications.

It now seems likely that campaigns to boost mental health awareness sometimes backfire and pathologise ordinary unhappiness. School-based prevention initiatives are sometimes ineffective and can even reduce wellbeing.

Most of all, it is becoming obvious that although there is a high unmet need for treatment, simply expanding the current mental health system – training more therapists, funding more sessions and services, further boosting awareness of mental health, embedding a therapeutic sensibility in more of our institutions – cannot be relied on to substantially reduce mental ill health.

Research on the so-called “treatment-prevalence paradox” demonstrates that large increases in service provision have failed to reduce rates of mental illness. Current treatment practices have only modest efficacy in real-world settings. Reasons likely include the complexity and recurring nature of many mental health problems, and the low quality implementation and short-lived benefit of many treatments.

Some treatments also clearly do more harm than good, for some patients. A recent evaluation of Australia’s Better Access program, which gives Medicare rebates to help people access mental health care, found that patients who sought help for relatively mild distress were three times more likely to deteriorate than to improve (patients in more severe distress typically improved).

In this context, Shrier has some grounds to be sceptical that doing more of the same will turn around the mental health crisis. There is no question that more needs to be done – but believing that the solution is to scale up current practice seems, as Samuel Johnson said of a second marriage, a triumph of hope over experience.

Shrier addresses her concluding chapters to parents, urging them to reclaim the confidence that they know what’s right for their child. The trouble is, parents rarely know to which of Shrier’s “two distinct groups of young people” their child belongs.

How could they know? No bright line separates the supposed victims of therapy culture from the profoundly ill. Faced with a loved one’s distress, what can parents do but seek the forms of help that are currently available?

Our young people will continue to be funnelled toward mental health treatment in alarming numbers. We can only hope it will become more effective and less necessary.

Nick Haslam receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.