In July 2021, Jack Dempsey, the mayor of Bundaberg, delivered an official apology for Northern Queensland’s past reliance on the indentured labour of Pacific Islanders, many of whom were kidnapped (or “blackbirded”) and forced to work on the state’s cane plantations. “To say sorry,” explained Dempsey, “is a start in the healing and the hope for a better relationship going forward.”

The emotional response – equal parts sorrow and relief – from the local Islander community confirmed the gesture’s importance. “I’m thinking about my mother and my brother and my aunties who have all passed on,” said Aunty Coral Walker, the president of the Bundaberg South Sea Islanders Heritage Association. “It would have meant a lot to them because they were a part of that era where they knew about blackbirding.”

But if the Bundaberg apology began a healing, it by no means completed it. On the contrary, the statement highlighted the inadequacy of Australia’s reckoning with its past.

That’s because the practice Dempsey described – sometimes known as “sugar slavery” – was not a minor or incidental phenomenon. In fact, it was so important to plantation owners that, to defend it, they briefly contemplated separation from the rest of the colony, with Townsville mooted as the capital of what many observers dubbed a “slave state”. This “scheme for the extension and perpetuation of the slavery system” showed, one journalist claimed at the time, that Queensland had become “what the United States were before the Wars of the Secession”.

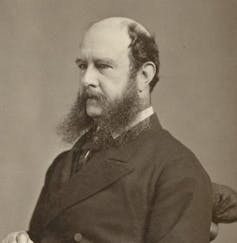

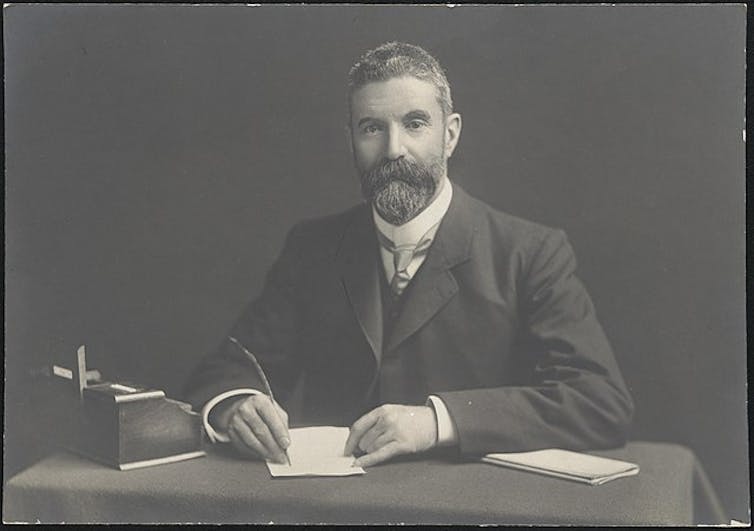

Similar references to civil war occurred again and again during the debates prior to the federation of the Australian colonies. Slavery and its consequences – both in Queensland and in the American South – obsessed Australia’s founders, and fundamentally moulded the country they created. Australia’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton, explained, quite accurately, that the “limited slavery” of the cane fields had agitated “the whole of Australia” and so was “a question which belongs to the Federation we have succeeded in establishing”. He also outlined the shocking philosophy upon which he considered Australia based:

I do not think either that the doctrine of the equality of man was really ever intended to include racial equality. There is no racial equality. There is basic inequality. These races are, in comparison with white races – I think no one wants convincing of this fact – unequal and inferior. The doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman. There is deep-set difference, and we see no prospect and no promise of its ever being effaced. Nothing in this world can put these two races upon an equality. Nothing we can do by cultivation, by refinement, or by anything else will make some races equal to others.

It’s impossible to understand that speech – and Barton’s conviction that, in dismissing racial equality, he spoke for the nation – without thinking about the sugar fields of Queensland and what was done there.

The French historian Ernest Renan described forgetting as “an essential factor in the creation of a nation”, since patriots do not want to remember the “deeds of violence” at the origin of all political formations. In the Australian context, a strange contradiction contributes to the ongoing amnesia about slavery and its consequences.

From the very beginning, enslavement shaped white settlement in Australia – and so, too, did abolitionism. That paradox, a peculiar entwinement of two ostensibly antagonistic impulses, makes for a complicated narrative, one that cannot be grasped simply as a local version of the better-known American story.

But if regret is to bring change, we must comprehend what we’re apologising for and why. The great abolitionist Frederick Douglass, a man who had escaped enslavement in 1838, described the past as a mirror that could, if used correctly, convey “the dim outlines of the future” and, perhaps, “make them more symmetrical”.

With that in mind, let’s talk about Australian slavery.

‘No slavery in a free land’

In 1788, England remained the most important slaving nation in the world, a country that, from the 17th century until 1807, conveyed a dizzying 3.25 million people out of Africa and into bondage.

The planners of the new convict colony in New South Wales drew directly on logistical skills acquired through Britain’s long involvement in the slave trade. They contracted the Second and Third Fleets to one of London’s biggest slaving firms, the merchants Calvert, Camden and King, who duly showed the same care for British convicts as they did for African slaves. Some 25 per cent of prisoners died on the voyage; 40 per cent succumbed within six months of arrival.

In New South Wales, the men and women labouring on the settlement were officially described as “in servitude” until they became “emancipated”, a vocabulary taken directly from the Atlantic trade.

Yet if slavery pressed on the colony, so too did anti-slavery.

Britain required New South Wales because, after the American War of Independence broke out in 1775, the English could no longer dump its criminals in the American territories. The same colonial uprising that disrupted transportation to the New World also turned public sentiment against slavery, an institution tainted by association with the ungrateful Americans.

That was why, in the month that the First Fleet sailed from Portsmouth, evangelical Christians in London launched the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade – an organisation that would eventually succeed in rendering slavery illegal in Britain.

A few years later, the Haitian revolution – perhaps history’s greatest uprising of the enslaved – would intensify respectable concern about the dangerous instability of slave societies. The visceral fear of black revolt induced merchants enriched by trading Africans to consider the new opportunities of the factory system, shifting Britain’s economy away from plantation agriculture to manufacturing and other, more modern, industries.

All of that affected the Australian colony. The more far-sighted members of the British elite had no desire to replicate the American disaster – and they most definitely did not want to found a new Haiti in the Pacific. So, before the First Fleet even departed, its commander, the 50-year-old naval veteran Captain Arthur Phillip, explicitly eschewed any intent to allow enslavement in the settlement.

“There can be no slavery in a free land,” he declared, “and consequently no slaves.”

In 2020, with Black Lives Matter protests spreading globally, Prime Minister Scott Morrison took a question from a radio host about the removal of colonial statues. In response, the Prime Minister defended the European settlers as relatively enlightened men, committed to ideals of freedom in New South Wales.

“It was a pretty brutal place,” he concluded, “but there was no slavery in Australia.” The comments brought widespread condemnation, and the Prime Minister quickly acknowledged that “hideous practices” had indeed occurred.

Yet Morrison’s initial point was not entirely wrong.

Phillip had, indeed, promised a free colony. So how did his pledge affect the “hideous practices” the PM described?

In 1788, mainstream abolitionism was not especially radical. The evangelicals, with their concern for human souls, considered chattel slavery – the legal ownership of one man by another – a denial of the personal agency so central to Protestantism. But, as moral campaigners, they also approved of punishing sin – and in the late 18th century there was plenty of it to punish.

In Britain, the enclosure of the English commons had driven impoverished rural populations into cities like London. Swelling unemployment meant crime and rebellion. To control the desperate and the jobless, the authorities passed harsh new laws, a legislative program designed to quell disorder and ensure a pliant workforce for the factories. The Riot Act banned public disorder; the Combination Act made trade unions illegal; the Workhouse Act forced the poor to work; the Vagrancy Act turned joblessness into a crime. Eventually, over 220 offences could attract capital punishment – or, indeed, transportation.

As we have seen, convict transportation – a system in which prisoners toiled without pay under military discipline – replicated many of the worst cruelties of slavery. Yet, rather than fostering opposition to the forced labour of transportees, mainstream abolitionism helped justify it.

Middle-class anti-slavery activists expressed little sympathy for Britain’s ragged and desperate, holding the urban lumpenproletariat responsible for its own misery. The men and women of London’s slums weren’t slaves. They were free individuals – and if they chose criminality, the abolitionists reasoned, they brought their punishment on themselves.

That was how Phillip could decry chattel slavery while simultaneously relying on unfree labour from convicts. The experience of John Moseley, one of the eleven people of colour on the First Fleet, illustrates how, in the Australian settlement, a rhetoric of liberty accompanied a new kind of bondage.

As Cassandra Pybus documents, later in life, Moseley claimed to have been employed as a “tobacco planter in America”. By that he almost certainly meant that he had been enslaved on a plantation in the Tidewater region of Virginia and Maryland. How had he washed up in Sydney?

Like several of the black First Fleeters, Moseley fought for Britain during the American Revolution. That was because Lord Dunmore, the last British governor of Virginia, had offered liberty to “all indented Servants, Negroes, or others […] that are able and willing to bear arms” against the insurrectionists.

Moseley, and others like him, chose freedom – and then faced recapture when Britain surrendered. One slave later said that the success of the revolt “diffused universal joy among all parties; except us who had escaped from slavery and taken refuge in the English army”. Desperate to evade their old masters, the formerly enslaved begged the retreating British for passage to London. Those who were successful remained free – but also, for the most part, unemployed, struggling in a strange and harsh city without friends or family.

Loyalists could, in theory, claim compensation for fighting in the revolutionary war. In practice, the authorities generally rebuffed pleas from ex-slaves, on the cynical basis that emancipation constituted sufficient reward.

“Instead of suffering by the war, he gained by it,” wrote an official about one claimant, “for he is in a much better country where he may with industry get his bread, where he can never more be a slave.”

Moseley, like so many others, struggled in the harsh city to get his bread. When he eventually turned from industry to criminal fraud, the contrast between British liberty and American slavery provided the ideological justification for the treatment he received. He was a free man; the court held him responsible for his own dishonesty and sentenced him to death. The eventual commutation of a capital sentence to transportation meant that armed guards marched a black ex-slave, chained once more by the neck and ankles, to the Scarborough, on which he sailed to New South Wales.

Phillip’s prohibition on chattel slavery was, on its own terms, genuine. But we need to understand what those terms were. For John Moseley, the “free land” of New South Wales brought only a replication of that captivity he’d endured in Virginia. His experience was not unique. As the poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht might say, throughout the settlement, the old strode in, disguised as the new. In years to come, colonial opposition to slavery would co-exist with, and even facilitate, various kinds of bonded labour – and nowhere more so than in Queensland.

‘A second Louisiana’

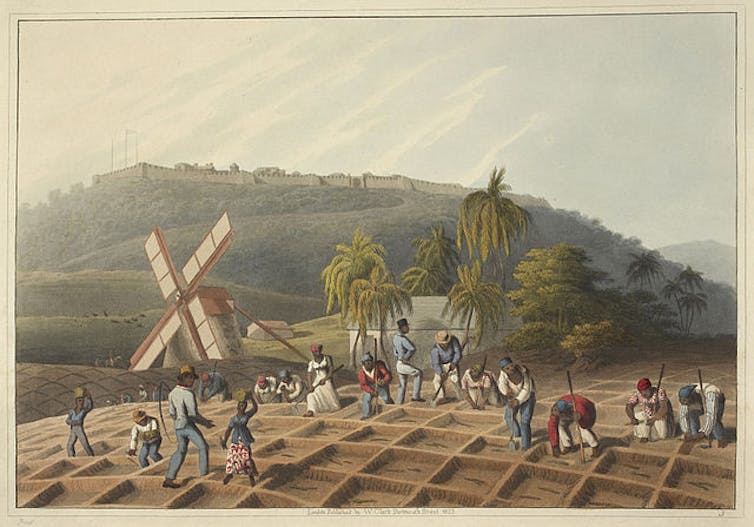

From the very start, the Australian sugar industry demonstrated how formal and real freedoms might collide.

In Tascott, New South Wales, you can still find a plaque celebrating the man who gave the town its name: a certain Thomas Scott, who, we are told, “arrived in the colony in 1816 [and] pioneered the sugar industry in Australia”.

The Tascott memorial neglects to mention Scott’s background in the slave trade. Yet that was how he developed his familiarity with sugar. As a young man, he assisted an uncle buying and selling Africans, before he began managing slave labour on his family’s plantation in Antigua.

Scott came to Port Macquarie in 1823, where Major Frederick Goulburn engaged him for an annual salary of £250 to grow sugar in the strange climate. Historians now agree that he failed miserably.

“How many times did you try to make sugar at the settlement before you made anything like it?” a contemporary mocked him. “What you made yourself was not fit for dogs to eat before the poor black man shewed you the way.”

That “poor black man” was another Antiguan, James Williams.

Where Scott was an ex-slaver, Williams was an ex-slave. He had somehow escaped to England, where, like Moseley, he resorted to crime. Sentenced to seven years transportation, Williams arrived in Sydney in 1820. Another theft saw him banished to Port Macquarie. In that town, a full year before Scott’s arrival, he established a viable crop from eight joints of cane, using the “knowledge of the growth of that Plant” he had acquired as a slave.

Despite the successful production of “very good Sugar and Rum”, Williams never adjusted to life in the colony, spending the rest of his days in and out of various forms of custody. By contrast, Thomas Scott, confident the rival claims of a “poor black man” would not be heeded, basked in an entirely undeserved reputation as the father of Australian sugar, even receiving an annual pension for his supposed achievements. In that foundational moment – an ex-slaver exploiting an ex-slave – the racial dynamic of the industry was already visible.

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, many Europeans in Australia sympathised with the Confederates, particularly after the Unionists briefly seized the Trent, a British Royal Mail steamer. The Melbourne Argus anticipated war between Australia and the northern American states, arguing that that “as a matter of sound precaution, citizens of the United States now resident in Victoria should be placed under surveillance”. Some of the gun emplacements still visible in Sydney Harbour date back to that fear of invasion by the Yankees.

In the context of that widespread enthusiasm for the South (the welcome extended to the Confederate ship Shenandoah in Melbourne in 1865 led one of its officers to conclude “the heart of colonial Britain was in our cause”), Queenslanders dreamed of building a “second Louisiana”. They could, they thought, capitalise on the disruption of the international cotton and sugar trades, if only they could establish a viable local crop.

But how might they emulate agriculture from a slave state?

Attempts to attract English workers to Queensland did not succeed. The men that came found the conditions unbearable, something the colonists attributed not to the innate unpleasantness of cutting cane in the sticky heat, but to the racial unsuitability of white labour to the tropics. So, in 1863, the shipping tycoon Robert Towns (the man who gave Townsville its name) tried another approach.

Towns knew that, back in 1847, an entrepreneur called Benjamin Boyd – another man with a background in Caribbean slavery – had scandalised the colony by transporting men from the Pacific Islands of Tanna and Lifou to supply his cattle station with labour. The “signatures” on the documents that indentured them were thumb prints from illiterate men who had never before seen cattle; their “contracts” bound them to work for a pittance however Boyd commanded. Some of the labourers revealed their genuine feeling by fleeing as soon as they could; the others demanded to be sent home. Boyd’s business collapsed and he decamped to California.

In Boyd’s inauspicious venture, Towns glimpsed a solution, a means by which he might recreate Louisiana in Queensland. The insatiable demands of the textile industry meant, he thought, that cotton plantations would be far more profitable than Boyd’s cattle stations. Accordingly, Towns chartered a ship called the Don Juan and sailed it to the New Hebrides from where it returned crammed with Islanders destined for Towns’ huge property near the Logan River.

The Civil War ended before Boyd could prove his experiment a success. But though peace dashed prospects for a Queensland cotton boom, a planter called Louis Hope realised that cotton fields could also be used for sugar, a commodity always in demand. He duly sent out ships to obtain indentured labour of his own.

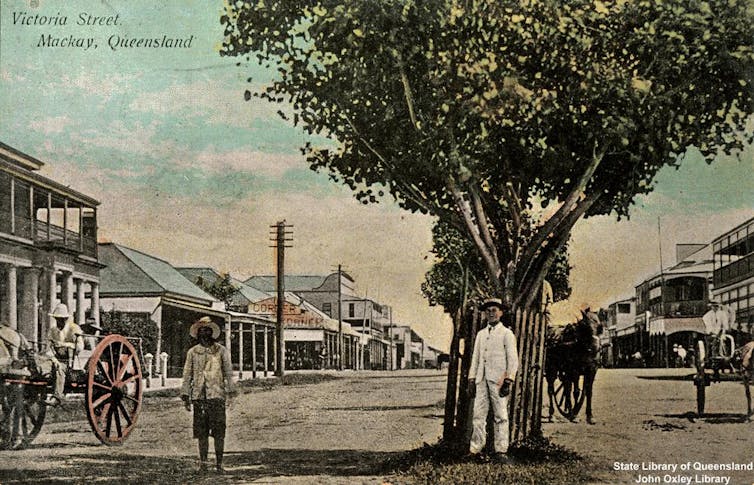

That was how it began. Between 1863 and 1904, 62,000 South Sea Islanders were transported to Australia, landing in Brisbane, Maryborough, Bundaberg, Rockhampton, Mackay, Bowen, Townsville, Innisfail and Cairns. Most indentured labourers arrived from the New Hebrides, with a substantial proportion taken from the Solomons, as well as smaller islands. By the 1890s, Pacific Islanders constituted 85 per cent of the workforce for Australian sugar.

Some came willingly, accepting – as desperate people do – unknown hardship to escape grinding poverty. Some, equally clearly, did not. Faith Bandler, the much-loved civil rights activist and hero of the 1967 Indigenous rights referendum, was the daughter of one such sugar slave. As a child, she’d listened to her father, Peter Mussing, describing his youth. He told Faith about

when he was kidnapped and taken into the boat by the slavers, and what it was like in the boat coming over from his island Ambrym in the New Hebrides, and how rough it was and how they were all held in the hull and how sick they were and those who died would be thrown overboard and how it was when the boat would arrive in Australia and how strange everything seemed to him.

Paradoxically, such experiences – so reminiscent of the Middle Passage endured by slaves brought across the Atlantic Ocean – coincided with a hardening of official hostility to slavery throughout the British Empire. In 1833, the parliament in Westminster had officially legislated abolition, with enslavement thereafter disdained as contrary to English principles of liberty. The politicians allocated an extraordinary sum of £20 million (about 40 per cent of Britain’s total income) to restitution: an amount granted not to the slaves but to their owners, compensation to them for the loss of their “property”.

The records of those disbursements include a remarkable number of colonial Australians. Judges, statesmen, bankers, even the poet Adam Lindsay Gordon: the upper echelons of Australia society contained many men who had either personally kept slaves or belonged to families that did.

In the bigger population centres, the beneficiaries of enslavement generally distanced themselves from their less than reputable past. The tropical north, however, was different. There, those with a background in Caribbean slavery could recreate something of their old ways.

Louis Hope, for instance, set himself up (according to one biographer) “as a landed aristocrat”, with a grand mansion at Ormiston, an estate akin to those his slave- owning relatives occupied in the Caribbean. He was not alone in his affectations. A visitor to Queensland in the late 1870s and early 1880s described the planters living along the river at Mackay:

Their houses as a rule, are extremely comfortable, and very well furnished, and the gardens of many of them are paradises of beauty. In good times, they make tremendous profits, and their occupation chiefly consists in watching other people work, in the intervals of which they recline in a shady verandah with a pipe and a novel, and drink rum-swizzles. Most of them keep a manager, so that they can always get away for a run down south, or a kangaroo hunt up the country.

The men did not merely adopt a lifestyle associated with New World slavery. They also relied on its techniques and its personnel.

Hope, for instance, acquired his sugar plants from the old slaver Thomas Scott. He hired supervisors from Jamaica and Barbados, looking for those with experience driving plantation slaves. To obtain the men for his fields, he turned – just as Boyd had before him – to a certain Captain Lewin, a notoriously shady character.

The Royal Navy’s Commander George Palmer described Lewin’s vessels as “fitted up precisely like an African slaver, minus the irons” and noted that, “I heard of him [Lewin] at every island I was at as a man stealer and kidnapper”. Lewin escaped conviction for a rape committed on one of those ships when a Brisbane court held that his 13-year-old victim could not give evidence since “she was not a Christian, and there were no courts of law in her country”, ignoring the testimony of the Islander witnesses who described the girl’s screams.

Between 1863 and 1868, this was the man responsible for “recruiting” nearly half the Islanders who arrived in Australia.

An illegitimate offspring

The uncontrolled growth of blackbirding eventually spurred the Polynesian Labourers Act, an attempt by the Queensland government to enforce some sort of regulation. The law required recruiters to get a licence; it mandated certain minimum standards on voyages where previously passengers had often simply been imprisoned in the holds.

Yet conditions did not necessarily improve. In general, the treatment of Islanders in Queensland depended less on legislation than on how desperately the planters needed labour at any given moment.

Some young men found indenture quite bearable, so much so that when one contract ended, they signed on for another, before eventually returning to their homes with cash in their pockets. Yet when the sugar boom of the 1880s fostered a scramble for cutters, the cruelties intensified. On occasion, recruiters – desperate to fill their quotas – travelled to islands where blackbirders had never previously visited and simply grabbed whomever they could find.

In 1884, at the height of that demand, a vessel called the Hopeful opened fire on Islanders who resisted being stolen, killing at least 38 people and possibly more. Its crew faced trial for kidnapping and murder; a subsequent Royal Commission found that only nine of the 480 people “recruited” by the ship had understood the supposed agreements they’d signed. The commission described the Hopeful’s expedition as “one long record of deceit, cruel treachery, deliberate kidnapping and cold-blooded murder”.

The sailors were subsequently released, after “public indignation [about their convictions] in Brisbane and the coast towns waxed to fever heat” and some 28,000 people signed a petition calling for clemency.

The massive support for the Hopeful’s crew needs to be understood in the context in which indentured labour was advocated. Hope, and the others like him, did not see themselves as recreating slavery. On the contrary, they declared their opposition to the practice. The Islanders were not, they said, chattels. Rather than being bought or sold, the men were employees, hired like any other workers. They received money in return for the contract; when their term expired, they could leave.

This was not altogether untrue. Legally, the Islanders were never enslaved. Unlike the slaves in America, they were not officially classified as property. Some managed to improve the terms of their engagement, winning better wages and less brutal conditions. By the 1890s, many were engaged in something more like wage labour.

Nevertheless, the reason the sugar barons wanted Islanders did not vary: they understood that white men could impose upon indentured non-white labourers a discipline that Europeans would not accept. They could pay them less (and sometimes not at all). They could beat them and belittle them and abuse them, confident no law would intervene, and they could work them relentlessly under regimes that regularly proved fatal.

Queensland was not the Americas. What was done in Australia was different and needs to be understood on its own terms. The historian Emma Christopher suggests that, rather than being imagined as analogous to Atlantic slavery, the trade in the Pacific might be thought of as one of its illegitimate offspring: a forced labour both reminiscent of and distinct from the practices of the New World. Nevertheless, a legal case in Rockhampton in 1868 illustrates the aptness of the term “sugar slavery”.

In January that year, a man called John Tancred faced charges under the Master and Servants Act after a conflict with one Arthur Gossett over an Islander boy identified only as “Towhey”. Though bound to Gossett, the child had fled his employment to join men from his own island who were labouring for Tancred. Their teary reunion provoked a legal dispute between two white men about the “lawful ownership” of Towhey (known by a quite different name among his own people) – a matter settled when Gossett proved his claim by identifying a brand on the boy’s leg.

“The advantage,” explained the Rockhampton Bulletin,

of the branding these intelligent islanders who cannot speak English and who make crosses to their agreements, has been made very manifest by this case, and, perhaps, it may not yet be too late for the Assembly to insert a “branding” clause in the Polynesian Laborers Bill.

The Assembly did not adopt that suggestion. It did, however, accept an amendment proposed by Hope himself (who became a member of the Queensland Legislative Council in 1862), which decreed that if an indentured labourer “absent[ed] himself from the place of employment for a greater distance than one mile […] without a pass from his employer”, he would be “liable to apprehension and punishment” – a clause justified by the need for “the employer to retain control over his laborers”.

The Australian press described the Islanders as “kanakas”. In its original, Hawaiian context, kanaka meant “free man”. In Australia, it signalled the opposite, as no less an authority than the Governor General confirmed.

Like many of the planters, Sir Anthony Musgrave had come to Australia from the West Indies. Like them, his family had owned slave-run plantations – and so he knew enslavement when he saw it. In Australia, he privately described the recruitment of Islanders as “a system & arrangements wh. are as much like slavery & the slave trade as anything can well be wh. is not avowed as such”.

By 1884, the annual mortality rate for Islanders in Queensland had climbed to 147 deaths per 1000 people. Everyone knew why: as the Brisbane Courier reported, the causes of mortality were “indisputably plain; the islanders were being killed mainly by overwork, insufficient or improper food, bad water, absence of medical attention when sick, and general neglect”.

The harshness was not accidental. “[Islanders] must be treated with firmness,” explained the planter J.W. Anderson,

they do not expect much leniency and would take advantage of it. Above all, they must not be treated too well, according to our notions […] for their minds are so constituted that they do not appreciate such treatment.

Anderson’s belief that Islanders were innately predisposed to appreciate brutality illustrates how Queensland sugar depended on the most pernicious ideological legacy of the Atlantic slave trade: modern racism.

Built upon a groan

The philosophical underpinnings of slaving might seem obvious. The perceived inferiority of Africans enabled, we assume, merchants to buy and sell them as commodities. But that’s quite wrong. Africans weren’t enslaved because they were black. They were black because they were enslaved, with the vast profits in Atlantic slavery giving rise to entirely novel forms of classifying humanity.

Slavery existed in the past, of course. But in the ancient and medieval worlds, enslavement related typically to conquest or religion rather than “race” – a concept that didn’t really exist as we know it today. Anyone could become a slave after a battle; slaves could sometimes free themselves by converting to their masters’ faith.

Slavery was not, in other words, a condition attached permanently to a certain type of person so much as an unfortunate fate that might befall anyone.

The system imposed in the Caribbean and the Americas was different. The immensely profitable cultivation of cotton and sugar required vast quantities of labour, not least because the plantations often proved fatal to the men and women toiling in them. Begrudging any cessation of production, planters in the New World did not release converts; they deemed the sons and daughters of slaves to inherit their parents’ status.

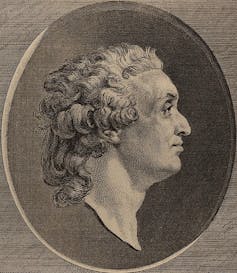

Accordingly, slave owners developed a different rationale for their system, one under which the skin pigmentation of the enslaved – previously an entirely incidental feature – defined them, as an indelible quality that marked men and women as suitable for servitude. The French philosopher and mathematician Nicolas de Condorcet pointed out that the new theories made “nature herself an accomplice in the crime of political inequality”. Indeed, the identification of “blackness” with inferiority corresponded with an equally novel claim about the superiority of “whiteness”, one that provided a legitimation for the spread of British power.

From the very start, such ideas had underpinned the establishment of the Australian colonies.

The “natives”, Phillip complained soon after landing, were “far more numerous than they were supposed to be”. Their abundance mattered because it undercut the legal foundations of the entire colony. Phillip, like everyone else on the mission, knew perfectly well that international law forbade a nation claiming sovereignty over territory inhabited by others.

The settlers resolved the jurisprudential problem by ignoring it. The colony might have been illegal, but race theory allowed the colonists to believe themselves committed to universal law, even as they more or less entirely excluded Indigenous people from its remit.

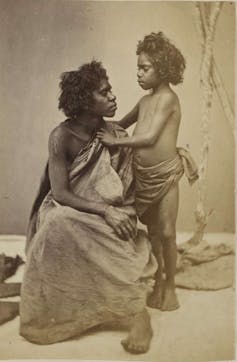

That provided the pattern for everything that followed. In theory, Indigenous people enjoyed all the protections of British subjects. In practice, they were often treated as animals – or, indeed, slaves.

As late as 1899, a Select Committee of the South Australian Parliament received grotesque testimony about the sexual slavery to which Aboriginal women were subjected. One policeman explained that the rape of “lubras” (a racist term for Indigenous women) was commonplace.

“If half the young lubras,” he said,

now being detained (I won’t call it kept, for I know most of them would clear away if they could) were approached on the subject, they would say that they were run down by station blackguards on horseback, and taken to the stations for licentious purposes, and there kept more like slaves than anything else. I have heard it said that these same lubras have been locked up for weeks at a time – anyway whilst their heartless persecutors have been mustering cattle on their respective runs. Some, I have heard take these lubras with them, but take the precaution to tie them up.

A few years later, persistent accounts of abuses in Western Australia led to a Royal Commission in that part of the country. Under its auspices, Walter Roth, the former Chief Protector of the Aborigines in Queensland, produced a lengthy document chronicling the proliferation of forced labour.

“Here at our own doors,” said the Melbourne Advocate,

we have had revealed a system of slavery so revolting in its brutality, and so inhuman in all its details, as to equal all the horrors that have been alleged against the slave owners in America and the military expeditions in Central Africa.

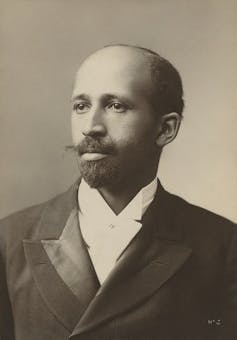

The activist and historian W.E.B. Du Bois once described America as “built upon a groan”. Something similar might be said about the colony of Australia, at least as far as Indigenous people were concerned.

White Australians tend to imagine frontier violence largely in images derived from first contact: a matter of sharp, almost accidental, clashes as European and Indigenous worlds collided. In fact, the worst depredations were considerably more deliberate, and they escalated as the settlers established themselves. The increasing independence of the colonies during the second half of the 19th century reduced the humanitarian influence exerted by London and allowed the settlers to bring to the frontier techniques of dispossession refined through bloody experience.

The European occupation of Queensland took place later than in other states. As late as 1850, the state contained only about 8000 white settlers. Thereafter, a rapid influx of Europeans unleashed horrific violence against an Indigenous population of about 200 000 people, in a process the colonists considered both necessary and inevitable.

“We should be sorry to see the natives treated with cruelty and oppression,” explained a Queensland cabinet minister to parliament in 1861, “but that the settlers will increase and the colony expand, is a result which the rules of nature render positively certain.” The whites could not and should not be prevented from taking the land and “if the inferior race suffers in the process, that is only what has happened in all such cases, and will happen again until the end of time”.

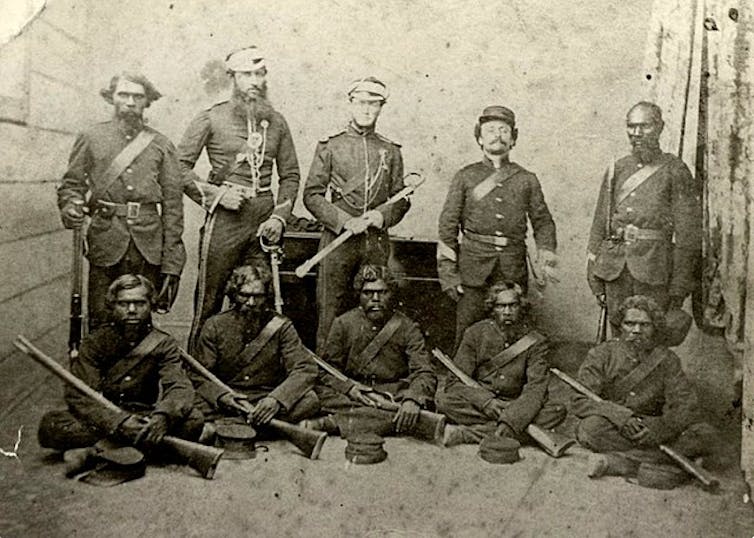

In reality, his government was less a passive observer of “cruelty and oppression” than a key facilitator. The authorities established the Queensland Native Mounted Police in 1855, equipped its members with high-powered rifles, and paid them to “disperse” any Indigenous people they located. As another parliamentarian acknowledged, the euphemism “dispersal” meant “nothing but firing into them”.

The Mounted Police were, in contemporary terms, death squads – and some historians estimate they eventually killed as many as 40,000 Aboriginal men, women and children.

As late as 1880, the liberal Queenslander described the slaughter on the frontier, noting that the Indigenous inhabitants of territory into which Europeans moved were

treated exactly in the same way as the wild beasts or birds the settlers may find there […] Their goods are taken, their children forcibly stolen, their women are carried away, entirely at the caprice of the white men. The least show of resistance is answered by a rifle bullet; in fact, the first introduction between blacks and whites is often marked by the unprovoked murder of some of the former—in order to make a commencement of the work of “civilising” them.

That article provoked a year-long discussion, in which the Queenslander’s contributors demonstrated how the genocidal campaign against Indigenous people had normalised measures unthinkable in any other context.

A writer styling himself “Never Never” called, for instance, for a speedier genocide, urging the “exterminating force” of the Native Police to work more “thoroughly and effectually”.

“Is there room for both of us here?” he asked. “No. Then the sooner the weaker is wiped out the better, as we may save some valuable lives in the process.”

Others, like a certain “Outis”, argued for what he saw as a more liberal solution. He suggested that, rather than being murdered, Aboriginal people should be treated like “rogues and vagabonds”, and forced to work so that they will have no time to hatch mischief".

Outis noted how planters were bringing “large numbers of South Sea Islanders to Queensland” under laws that forced them to work as directed by their employer. He argued the same policy could be applied to Indigenous people forcibly removed from their land:

Only get the blacks out of their own district and it would rest with the employer to make them work; some harshness would no doubt be necessary (as I am told is also the case with Kanakas), but I firmly believe that firmness combined with kindness, and the low rate of wages that the blacks would be paid, would make the employment of aboriginal labor a payable speculation.

For Outis, officers from India or Ceylon could enforce the necessary discipline – so long as they were “untethered by red tape”. A policy of enslavement rather than murder would, he said, remove ‘the present blood guiltiness that weighs upon us each individually as colonists’, and so would be worth whatever it cost.

“Is there no member of Parliament who will take this question up?” Outis wondered:

Are all so overburdened by the cares of the squatters, or diggers, who comprise their constituencies that they cannot spare the time to consider and devise a remedy for “the poor old nigger”?

As it happened, at least one MP did share his enthusiasm.

On 21 October 1880, the Queensland Parliament debated the role of the Native Police. In the discussion, John Douglas (who would later become premier) argued that the distinction between Islanders and Aboriginal people was not so great to extinguish “the hope that some use might be made of the latter”.

He pointed to Western Australia where “the natives had been […] in some cases captured, and as prisoners of war had been compelled to submit to a period of pupilage, afterwards becoming useful settlers”. Queensland, Douglas said, might follow suit by taking “the natives prisoner, instead of shooting down and killing them”.

He did acknowledge the legal difficulties in a policy “by which these people, taken in open warfare, might be kept in a state of captivity” but stressed it would “be a more benevolent process than shooting them down and taking their lives”.

The chamber did not embrace Douglas’s “benevolent process” (which would, of course, have been entirely illegal), though some years later a correspondent to the Adelaide Evening Journal reported that the Native Police were, in fact, selling into slavery the children of Indigenous people they had massacred.

The willingness of Queensland parliament to ponder the relative merits of enslavement over murder provides a particularly repellent example of the moral desensitisation arising from colonial dispossession. Amid the cruelty inflicted on Indigenous people, the indentured labour of Islanders could seem entirely unremarkable.

Sugar versus slavery

The relationship between sugar slavery and the foundational racism of a colonial settler state makes an intuitive sense. We understand that the planters who built fortunes from forced labour were infused with a sense of their own biological superiority.

We might not grasp that those who denounced slavery were often even more avowedly racist.

In the Queensland parliament, the Liberal politicians attacked the planters’ reliance on Islander labour almost as soon as indenture began. They did so by objecting to the sugar barons polluting the colony with, as the Liberal MP Charles Lilley said in 1869, “men of an inferior race”.

“The British people are the possessors of this soil,” Lilley declared. “We hold the land in trust for our countrymen alone not for Polynesians or Chinamen.”

The parliamentary argument about the sugar industry was not a debate between racists and their opponents but a contest between different visions of whiteness. The Conservative Premier Sir Thomas McIlwraith, a man with personal interests in the sugar industry, expressed the perspective of the planters. He wanted, he said, a Queensland both successful and white. Economic prosperity depended on cane, a crop he thought Europeans racially incapable of harvesting. Hence the necessity for a subservient caste of Islanders, who could ensure Queensland remained “a white man’s colony, influenced by white men and owned by white men”.

His Liberal rival Samuel Griffith, on the other hand, argued that the importation of Islanders would foster the “degeneration which we have seen whenever the black and white races have endeavoured to mix”. If whites depended on slavery, they’d lose their racial consciousness and accept widespread immigration. Accordingly, Griffith advocated a purely European colony based on the rigid exclusion of all non-whites – in essence, attacking the proponents of sugar slavery for being insufficiently racist.

When Griffith won the 1883 election, his victory threw the sugar industrialists into panic. Politics in Queensland, the Sydney Evening News explained, was “fast narrowing itself down to the very simple issue – sugar versus slavery”, since “sugar plantations cannot be worked in Queensland without slave labour in some form or other”.

Fearing the collapse of their estates, the sugar barons contemplated secession. Seeking to marshal all those benefiting from the industry, they presented a vision of independence. They would, they declared, form their own colony, where they could employ on their plantations as much Islander labour as they saw fit.

In April 1885, a Northern Separation convention in Townsville attracted delegates from eleven towns in the region. A petition for secession gathered some 10,000 signatures, a not insignificant number in a population area of perhaps 19,000 European men. In parliament, Maurice Hume Black – a representative of the sugar interests – openly warned that North Queensland wanted to go its own way, while the planters John Ewen Davidson and Sir John Lawes argued their case to the Colonial Office in London.

For a while, it seemed entirely possible that Northern Separation – a movement led by some of the wealthiest and most influential people in the region – might prevail. In his book A Land Half Won, historian Geoffrey Blainey suggests that, had that occurred, northern Queensland “would probably have remained outside the new Commonwealth of Australia”, becoming “a version of Rhodesia or the old American confederacy of cotton states”.

Many people at the time, with the American Civil War fresh in their minds, thought the same. “If tropical Australia is politically severed from the South,” warned the Brisbane Courier,“[…] we may leave to our children such a legacy of evil as that from which America only rid herself by the most terrible fratricidal war which the modern world has seen.”

That didn’t happen because, with their dream of Northern Separation and sugar slavery, the planters faced two powerful opponents.

Overseas, Britain reacted to the petitioning Queenslanders with unabashed horror. If anything, London’s concern about the social instability of chattel slavery had only increased since in 1788. In the wake of the civil war in America, British diplomats regarded the prospect of a new antipodean Confederacy as disastrous. As the Times noted, England bluntly informed the planters and their supporters that it would “not permit the establishment of a slave state in Northern Queensland”.

At home, the separatists confronted a different problem. After the gold rush, Chinese immigration had become the focus of racist agitation all over the colony. As early as 1855, Victoria had passed “an Act to Make Provision for Certain Immigrants”, which imposed a discriminatory tax on the Chinese. Other states followed. In 1857, Europeans physically attacked Chinese miners in the Buckland River gold fields; similar riots took place at Lambing Flats in 1860 and 1861. Many leaders of the newly-formed trade unions blamed the Chinese for driving down wages and so called for racial exclusion, a policy famously expressed in the slogan used by the pro-labour Bulletin: “Australia for the White Man”.

Politicians agonised over whether a colony reliant on a non-white workforce would remain sufficiently British. Many saw the Queensland plantations as a dangerous wedge, a crack in the white wall through which other races might insinuate themselves.

In the days of Arthur Phillip, anti-slavery had legitimised transportation. It now served an even more perverse cause, providing a moral justification for those demanding complete racial exclusion.

The Rockhampton-based Daily Northern Argus, for instance, attacked sugar-growersfor their “extraordinary persistence” in agitating for a cause that had already been defeated in the southern states of America. Yet the editorialist’s loathing for what the paper described as a “slave colony” culminated in a lurid vision of the sugar industry facilitating a Chinese takeover.

“The Mongolianisation of North Queensland,” the Argus declared, “is only an advance operation of the Mongolianisation of all of Australia.”

The advocates of Northern Separation denied, again and again, any intent to create what the press referred to as a “black state”. Again and again, they were attacked on precisely that basis, with secession decried as a pretext for slavery, and slavery as a threat to whiteness.

In 1885, Griffith announced that he would prohibit the importation of Islanders within five years. His declaration promised to end the whole controversy, committing Queensland to the Liberal vision of a racially pure nation, rather than the Conservative plan for apartheid. But before the plan could come into operation, the Great Depression of the 1890s struck, threatening the state with economic ruination. Baulking at the prospect of closing the sugar industry in such desperate times, Griffith united with his former rival McIlwraith to delay the ban.

The prevarication by “the Griffilwraith” (as the press dubbed the unlikely alliance) transformed the sugar debate in Queensland from a local dispute into a national issue, one of the major controversies preoccupying colonial politicians as they planned an Australian federation.

‘The necessary complement of a single policy’

The present location of Canberra, halfway between Melbourne and Sydney, echoes arguments made by Queensland secessionists.

In 1886, John Murtagh Macrossan, a prominent Northern Separationist, had proposed establishing the capital of the new Queensland state away from existing population centres so as to minimise regional jealousies. The logic later prevailed with the creation of Canberra.

Even though the Queenslander Samuel Griffith played a major role in drafting a national constitution, the unresolved tension over indentured labour limited the participation of his state in the federation debates. The representatives of the other colonies might have been divided over the merits of free trade versus protectionism, but they shared the goal of an entirely white Australia. That was, indeed, a major motivation for unity: as Alfred Deakin later explained, only federal legislation could prevent the discrepancies between different laws that constituted “a half-open door for all Asiatics and African peoples”.

With the national project at odds with the planters’ continued hopes for some form of indenture, a divided Queensland did not attend the 1897/98 constitutional convention. It was only in the following year, when the sugar industry had been placated by the offer of federal compensation, that a pro-federation referendum narrowly succeeded in the state – a victory that signalled majority support for racial homogeneity.

In the Westminister Review, T.M. Donovan explained the triumphant Liberal perspective:

Federation will bring us statesmen, an honest democratic franchise, and will, no doubt, in a short time rid us of the Asiatic and coloured labour curse. Under the federal flag a piebald race will be an impossibility. […] total exclusion alone can save Queensland from the coloured problem of the United States.

His reference to America expressed a common perception that the legacy of slavery had polluted that country, in ways that young Australia, with its commitment to racial purity, needed to avoid. When Prime Minister Barton introduced the Immigration Restriction Bill by declaring non-whites to be fundamentally inferior and their exclusion something to be greatly desired, he did not consider the statements at all controversial.

The intensity of the discussion that followed (the Hansard account runs to nearly half a million words) was not the result of any programmatic disagreement among the speakers. On the contrary, the Leader of the Opposition George Reid declared unanimity on the aim that “the current of Australian blood […] not assume the darker hues”; the Protectionist Samuel Mauger cited “expert” opinion that bringing “the white man into contact with the black [would] suspend the very process of natural selection on which the evolution of the higher type depends”; and Labor’s James Ronald explained that Australians objected to “inferior races” because “they are repugnant to us from our moral and social standpoints”.

The debate centred not on the desirability of a White Australia (for on that the MPs were as one) but on how it might be obtained, after four decades of indentured labour had brought so many Islanders into the country. That was why slavery in the United States featured so heavily in parliament’s deliberations: it was invoked again and again as a cautionary tale of racial pollution.

America was, explained the Liberal MP H.B. Higgins, undergoing “the greatest racial trouble ever known in the history of the world” and so Australians should “take warning and guard ourselves against similar complications”. Foolishly, white Americans had failed to expel their former slaves. America would, he continued,

have been ten times better off if the negroes had not been left there. There are no conditions under which degeneracy of race is so great as those which exist when a superior race and an inferior race are brought into close contact.

A supportive press concurred. “The Australian Commonwealth,” explained Queensland’s General Advertiser,

at the outset of its career has the golden opportunity of preserving to its citizens the purity of race. The great American commonwealth had not quite such an advantageous opportunity, insofar as long before it was founded the negro race had partly become rooted in American soil.

Local parliamentarians pledged not to make the same mistake, congratulating themselves on the superiority of their constitution over the one ratified by the United States, on the basis that its Section 51 (the so-called “race powers”) allowed them, as Prime Minister Barton had explained, “to regulate the affairs of the people of coloured or inferior races who are in the Commonwealth”.

Attorney General Alfred Deakin went so far as to boast that “our Constitution marks a distinct advance upon and difference from that of the United States”. Its passages explicitly permitting racial discrimination enabled parliament to pass the Immigration Restriction Act (to keep non-whites out) and the Pacific Islands Labourers Act (to deport those Islanders already in Australia).

“The two things go hand in hand,” Deakin explained. Stopping the “lesser races” from arriving (with Islander recruitment ceasing in 1903) and expelling those who were currently resident: these were “the necessary complement of a single policy – the policy of securing a White Australia”.

The new nation thus signalled its birth by doing what the United States did not dare: ethnically cleansing its former slaves.

‘These people want to hunt us out of the country’

The deportations began in 1904.

By then, the Islanders resident in Australia numbered perhaps 10,000. Many had built lives for themselves after their terms of indenture ended: finding jobs, building houses, raising families. Some barely remembered the places from which, decades earlier, they’d been taken. They were incredulous they were expected to return.

“Is it really true that white people want to send all boys back to islands?” asked an Islander in Mackay. “[W]e been work well in this land for white people, then why they want to turn us out?”

From the start, they resisted. In 1902, more than 300 Islanders signed a petition that they presented to Queensland’s governor and, via him, to the king. It pleaded for an end to a policy “contrary to the spirit of English common law and of freedom, justice and mercy”, a scheme that would “induce for hundreds, if not thousands of us, misery, starvation or death”.

In Mackay in 1904, a man called Henry Tongoa organised a Pacific Islanders Association. The association held meetings across North Queensland, where speakers explained that white men had refused to work in the cane fields and had been “glad to get us to do so”. The planters had become rich on Islander labour, they said, “with good homes, buggies, horses, pianos, sewing machines and all sorts of other good things which they could not buy or have before we came to the country and worked hard for them”. Yet, despite that, “these people want to hunt us out of the country”.

The protests – and persistent fears by Queensland planters about labour shortages – forced a 1906 Royal Commission into the program. The Commission recommended exemptions, including for the elderly, for long-term residents, those who could prove themselves in danger, and people who had married others from outside their own islands. But the expulsions were not halted.

In desperation, Tongoa sailed to Melbourne with another petition, this time for Alfred Deakin. The signatories begged for citizenship for those who wanted to stay. They even offered to remove themselves to a reserve somewhere in the north, a place where, they said, they would pose no competition to white men and could put their “long experience of tropical cultivation to use”.

Deakin remained unmoved. After the 1902 petition caused a stir in London, he’d responded by emphasising parliament’s unanimity about racial purity (as well as slandering the signatories as “ignorant savages unable to read and write”).

He’d also resorted to the old trick of legitimating repression by fulminating against enslavement. In reply to British humanitarians in London, he expounded on the brutality of the blackbirders, the recruiters’ trickery, and the cruelty of the planters.

Slavery was an abomination, Deakin said – and the government was shutting it down. A supportive press chided the Islanders for the petition, with the Telegraph dubbing them “ill advised” for resisting measures so obviously necessary. The paper invoked the experience of America, where, it explained, “the negro was emancipated […] but he was left in the country”. That, the Telegraph explained, was a disaster not to be replicated:

Now he lives and multiplies. The presence of about 10,000,000 negroes in America, without civil rights, is a great danger. It might be a greater danger if he had civil rights.

The purported opposition to slavery slid, once again, into a justification for tyranny, legitimating a rhetoric that became, at times, almost fascistic. When, for instance, Deakin’s government accepted the Royal Commission’s recommendations – including the exemption for married men – the Bulletin published a call to make miscegenation a crime punishable by hard labour so as to avoid a race war similar to one being fanned by ex-slaves in America. Its correspondent concluded by proposing the boiling in oil of “nigger-loving legislators […] who recently voted in favor of non-deportation of those Kanakas married to white men” – a suggestion to which the magazine’s editor added his endorsement.

The novelist Christopher Isherwood once described broadcasts of Hitler as conveying a sense of a man dancing up and down on the tips of his toes while he spoke. The shrill, mad voices in the Bulletin and elsewhere give the modern reader a similar impression.

In that ideological environment, the deportations continued. By 1908, only 2500 Islanders remained: a few of them because they successfully hid and the others because they’d been exempted. Most, however, were herded on to boats, in a ghastly process that separated lovers, friends and relatives from each other and from the country for which they’d toiled for so long.

In an extra act of bastardry, the government defrayed the expense of a process that was meant to be funded by employers, instead using money from the Pacific Islanders Fund – a trust established to remit wages owed to deceased labourers.

The Queensland Evening Telegraph recorded the understandable bitterness of the deportees, voiced once they were beyond the reach of the police on the wharfs and the jetties.

“Goodbye you white —,” they yelled, and your — white Australia!“

A legacy of racism

What might an apology for sugar slavery address?

What was done in in the cane fields was not merely the responsibility of the planters who benefited directly from it. Its centrality to politics in Queensland and, later, to Federation, implicated the men most responsible for Australia’s foundation.

To be clear, the big names in colonial politics – Deakin, Griffith, Barton, Watson and others – did not defend slavery in the manner of, say, those Confederate leaders whose statues still mar towns across the American south. On the contrary, most of them railed against the practice, competing with each other and with state politicians in Queensland to make their disdain known. ”[T]his government thinks,“ explained Barton bluntly, "that the traffic in itself is bad and must be ended.”

Yet, almost without exception, politicians used their hostility to slavery to legitimate a generalised racism, which they then presented as the foundation of a new state. Barton, for instance, introduced the Pacific Islanders Bill as embodying “the policy, not merely of the government, but of all Australia, for the preservation of the purity of the race.”

“Let us keep before us,” urged the Labor MP James Ronald during the debate,

the noble idea of a white Australia – snow-white Australia if you will. Let it be pure and spotless.

Instead of facilitating justice, opposition to sugar slavery enabled institutionalised discrimination, a policy its advocates grotesquely draped in the garb of abolition.

The differences between indentured labour in Queensland and chattel slavery in the American south did not prevent Australian parliamentarians from comparing the two. In their discussions of the federation they were building, American slavery provided a constant referent. A past reliance on African labour had left, they said, the United States a piebald nation, subject to the mongrelisation that a white Australia would avoid. Racialised anti-slavery justified the expulsion of Islanders, an ethnic cleansing necessary for Ronald’s “pure and spotless” society.

As Deakin explained, White Australia meant “the prohibition of all alien coloured immigration, and more, it [meant] at the earliest time, by reasonable and just means, the deportation or reduction of the number of aliens now in our midst”.

With the passage of the Pacific Islands Labourers Act, the founders explicitly sought to control not just sugar slavery but also its historical legacy. That was the point. The law meant, they said, that white Australians – unlike their American cousins – could avoid the descendants of those they’d enslaved. The exclusion of the Islanders would excise an awkward history, with the slaves expelled from Australia’s border and its memory.

For a time, it seemed like they’d succeeded. The deportations marginalised the Australian Islander communities, with those who remained often forced on to the margins of white society, usually alongside an equally oppressed Indigenous population. Like African Americans under Jim Crow, Islanders faced segregation in schools, shops, theatres, swimming pools, workplaces and just about everywhere else. A raft of laws forbade them from working in the cane fields, with an industry that had relied overwhelmingly on Islanders in 1902 using nearly 90 per cent European labour by 1908. The resulting impoverishment was exacerbated by their exclusion from the welfare system – they could not, for instance, claim the old age pension until after 1942.

Yet, despite the best efforts of white Australia, the Pacific Islanders survived – and they did not cease fighting to reclaim their past.

The ceremony in Bundaberg came as the result of prolonged lobbying from Islander organisations, part of a campaign that is forcing official recognition of blackbirding and sugar slavery. “The full truth needs to be told,” explained Emelda Davis from the South Sea Islanders Association to the Guardian back in 2017.

It’s inaccurate not to talk about the trade in people that built this part of Australia and there’s a lack of knowledge about what happened. Our people are left out of the narrative.

That remains central to justice: an acknowledgment of the victims and what was done to them. But the reckoning cannot end there.

In 2019, on the 400th anniversary of enslaved Africans arriving in Virginia, the New York Times launched its “1619 Project”, a series of essays, events and podcasts intended to place the consequences of slavery at the centre of American history. “America,” explained Jamelle Bouie, one of its contributors, “holds onto an undemocratic assumption from its founding: that some people deserve more power than others.”

What might we say, then, about the assumptions fostered through the founding of Australia on 1 January 1901? Unlike in the United States, slavery was always illegal in Australia. From the colony’s first days, enslavement was understood as both a crime and a sin. No-one called himself a slaver, not even the overseers. That hostility to a practice still widely accepted elsewhere helped define the settlement and the nation it became, as the composer Peter Dodds McCormick recognised. “Australian sons, let us rejoice,” his lyric for a future national anthem urged, “for we are young and free.”

The line hinted at the ideological work that freedom performed, then as it does now. McCormick’s invocation of “youth” defined the nation in opposition to its Indigenous people and their ancient culture, identifying the country with its European invaders. His song implicitly excluded the Aboriginal population from the rights of citizenship, calling on Australian sons to celebrate a liberty they denied to others. By 1878, when McCormick wrote Advance Australia Fair, sugar slaves had been toiling in Queensland for more than a decade.

Australian politicians today praise a “national character” defined by tolerance and laconic egalitarianism. They recall a past exemplifying those traits, a chronicle of good-hearted larrikinism quite distinct from the depravities associated with other countries. Yet the record shows something different.

“We have decided,” declared Prime Minister Barton, “to make a legislative declaration of our racial identity.”

Australia’s first leader explicitly understood the ethnic cleansing that followed slavery (along with racialised restrictions on immigration) as definitive, a policy central to the nation’s self-perception.

In the process of federation, Queensland’s peculiar institution served as the grit around which Australia cohered, a persistent irritant that gave the new nation its shape. That’s a point on which Australians should ponder. The history of sugar slavery highlights a national obsession with racial purity, a corollary of the dispossession that white settlement entailed. The treatment of Pacific Islanders built upon the treatment of Indigenous people, the great weeping sore of antipodean history.

In thinking about that, we might also consider the contemporary use of self-congratulatory humanitarianism and the ways a very Australian rhetoric of fairness continues to legitimate official cruelties. When our politicians explain the indefinite detention of those fleeing persecution as a policy to prevent refugees drowning, their words echo previous invocations of morality in service of bondage, a tradition stretching back to 1788.

The American scholar Richard White once described history as the enemy of memory. “The two stalk each other,” he said, “across the fields of the past, claiming the same terrain.”

That encounter matters, not simply because of the abstract virtue of truth prevailing over delusion but because an acceptance of history might enable a different future to be built.

The story of Queensland sugar highlights a particularly degraded notion of freedom, one in which liberty for some justifies oppression for others. But that’s not the only way to understand the concept. The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, for instance, once described freedom as “what we do with what is done to us”, a definition that aptly describes the long struggle by Pacific Islanders, and many others, to build something better in Australia.

The past cannot be altered. But it can, perhaps, inspire a different future.

An extract from Provocations: New and Selected Writing – Jeff Sparrow (Newsouth)

Jeff Sparrow does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.