In early March, France’s first minister, Elisabeth Borne, announced that French companies failing to enforce the country’s gender equality criteria would be denied access to public contracts. The news adds yet another line to an already long list of incentives to boost women’s standing in the workplace.

In recent years, research has increasingly shown filling one’s company’s top positions with women not only makes ethical sense, but business sense, too. In the UK, one 2020 paper showed that the presence of women on executive boards significantly improved the performance of the country’s firms, in particular when three or more females were appointed and when they also held executive director positions. Another study on banks in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, found that entities with female CEOs invested more in sustainable environmental initiatives. And the former IMF chief, Christine Lagarde, in 2019, stated that closing the gender gap in employment could push up global GDP by 35%.

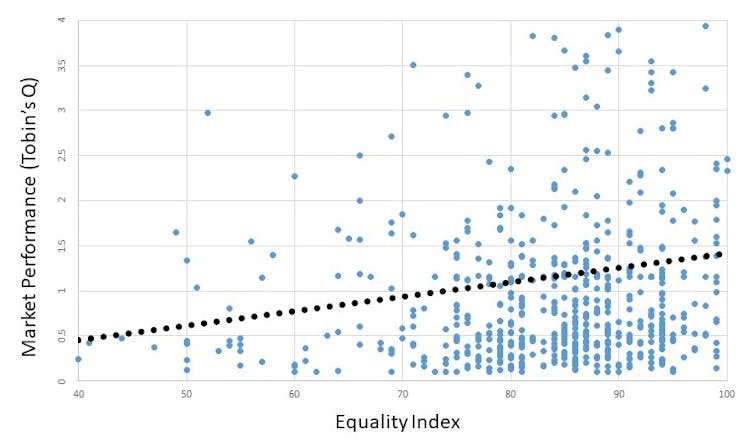

Due to be published in the International Journal of Corporate Governance in the coming months, our latest paper confirms this trend. Surveying data from 228 nonfinancial French listed companies from 2018 to 2021, we found evidence that companies who scored higher on the country’s “Gender Equality Index” also fared better in markets.

The French equality index

To boost women’s status in the workplace, the French government passed a law in September 2018 compelling companies with at least 50 employees to communicate information on gender equality. Taking its name from the then-Labour minister, Muriel Pénicaud (2017-2020), the Pénicaud index – also known as the equality index – obliges them to publish data on:

The difference in total remuneration between women and men weighted by grade and age group;

Difference in the rates of salary increases between men and women;

Difference in the promotion rates between men and women;

Salary increases for employees returning from maternity leave;

Gender balance of the top 10 highest-paid employees.

The availability of such information implies that French companies’ track record on gender equality is subject to public scrutiny, which can in turn affect investor confidence.

Gender index has spurred positive change

On the one hand, the results of our research are encouraging. The average Pénicaud Index for the surveyed firm is 84 points out of 100. In addition, we note that the equality index has increased over time, evidence that firms are willing to continuously improve female conditions. From this perspective, the effect of this law seems to be going in line with the government’s expectations. In her interview with Elle on 1 March, Borne effectively stressed the equality index’s main objective was not to punish firms, but to provide them with an incentive to change their policies and behaviours toward greater gender equality in the workplace.

And yet, we also believe there is significant room for improvement. If we look at the latest report, for example, we find only 2% of firms scored the maximum mark and a mere 61% provided their data on time. 2,354 firms obtained zero on the score on maternity leave.

There are some low-hanging fruit that companies can easily seize upon to boost their gender score. Take the one common blind spot which we observed among firms performing just below the maximum score of 100 points: female representation in the 10 highest-paid employees. Global consultancy group Keyrus SA scored 90 out of 100 in 2021, losing 5 out of 10 points in this area. That was also the case that year with the country’s energy provider, EDF, which clinched the maximum score in four out of the five categories included in the equality index, but failed to have a single woman to show in its 10 highest-paid employees. Women were also nowhere to be found in the highest earners of the country’s most popular TV channel, TF1, causing it to stagnate at 85 out of 100.

Such figures make clear that, notwithstanding companies’ efforts to boost gender equality in the workplace, corporate leadership remains the preserve of a small male elite. This is also the conclusion of a recent report by the European Women on Boards Association, which shows that, while boards of French firms lead the European Union in terms of female representation (45% on average of board members in France are females), only 15% of firms can boast female Chief Financial Officer and only 8%, a female Chief Executive Officer.

This is too bad, as firms prioritising gender equality tend to accrue significant financial benefits from it. In fact, our research finds a positive association between companies with higher values for their equality index and their market valuation and return on equity. The graph reports a simplified illustration about the association between one of the measures of market performance used in our research, Tobin’s Q, and the equality index of French firms. The trend line in black highlight the positive association between these two variables.

In addition, our analyses prove that independent auditors associated a lower audit risk (i.e., the risk that the annual report contains material errors) to companies with greater gender equality performance.

Our results encourage firms to give women the keys of companies’ C-suite, which remain stubbornly male-oriented even though the evidence indicates this is not in companies’ best interest. We also hope that the agendas of legislators and regulatory bodies keep promoting and enforcing gender equality across sectors.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.