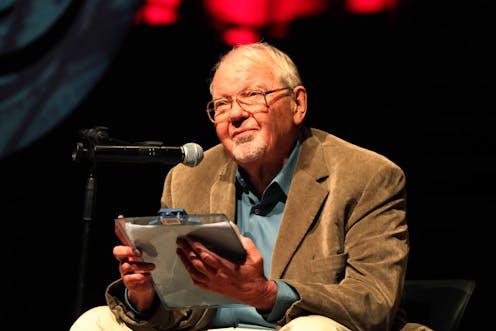

There are writers and critics, theorists and gurus. And then there is Fredric Jameson. Or there was. Because on September 22, at the age of 90, undimmed and over-productive as ever (three books in 2024 alone!), Jameson passed quietly away.

Over the course of his long and influential career, Jameson published 34 books and hundreds of articles. Along with his legendary conference interventions, they attest to perhaps the single most generous and sustained act of attention to cultural forms in human history.

His work took in a mind-boggling array of materials. Colin MacCabe once quipped that “nothing cultural was alien to him”. Though Jameson’s training was in German and French literature (under Wayne C. Booth and Erich Auerbach), he went on to master Western Marxism and French theory, before turning his tireless mind to architecture, theatre, film, television, opera, symphonic form, pulp fiction, painting, and what seemed to be every book written in any language worthy of our attention.

The title of world’s greatest Marxist critic has stuck to Jameson for over 50 years. There is no heir apparent. There is instead a vast international network of protégées, disciples, acolytes and apostles, who will endeavour to keep hope alive in the gathering darkness.

Hope is a word not often used in Jameson’s monumental oeuvre. He rightly preferred a more literary term: utopia. It defined him. Irradiated by what it portended – an achievable world freed from drudgery and stupidity and structural inequality – his prose sifted the cultural and artistic sediment of three centuries of capitalist domination.

Jameson held aloft for our astonished recognition the gleaming nuggets where traces of the good life lay coiled.

Generosity and the dialectic

Generosity is not a byword in the critical circles of the left. Where others invariably scrapped and stooped to bitter sectarian disputes, Jameson took the higher ground. He called it “the dialectic”, a habit of thought in which oppositions could be held comfortably in mind while the pulse of history rang out.

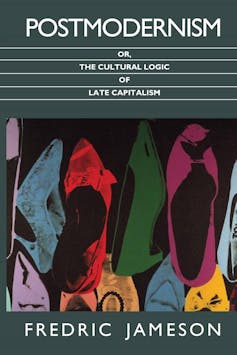

He was attacked for it, often nastily, and there must have been animosities and personal vendettas accrued over the years, but they never manifested in his published work. In the conclusion to his most famous book, Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1989), Jameson took on dozens of snide critiques. It is a masterclass in outflanking the enemy by seeing their point of view and then turning it around on itself.

The few intolerances that do suddenly flare out from Jameson’s infamously circuitous sentences speak more of idiosyncrasies than deeply held convictions. “Stories about priests are in whatever form intolerable”; “all beauty today is meretricious” – one learned to get along with these rare cranky asides, as one did with his unfathomable championing of writers like David Mitchell, because of the enormous sensitivity and analytic brio of his entire body of work.

And it was a single life’s work. Is there another writer of whom one could plausibly say that random pages taken from books written across six decades all seem plucked from the one continuous utterance? To be sure, references shifted as the theories Jameson took up to make sense of our world trended in and out of fashion. But there was a soaring, overarching argument: a colossal framework on which it all somehow hung together.

Now that it has come to an inevitable end, we may as well ask: what was that argument? It had powerfully to do with sensuality, with the sensuous basis of all aesthetic experience, with the living human body and its infinite capacity for pleasure and sensation and affection.

But it had just as much to do with the limits set on that capacity by social systems that are arbitrary and historical – “history is what hurts”, he once wrote.

It would be true to say that most thinkers tend to privilege one or other of these two dimensions of experience: the ludic or the structural. But Jameson straddled both comfortably. His unique signature, his style, was an effort to smuggle bodily pleasure back into august depictions of the limits set upon human flourishing. If that doesn’t sound particularly Marxist then, as Jameson implied often enough, you haven’t read enough Marx.

Our sensuous, creative, collaborative interdependency and inexhaustible drive to play – our thwarted “species being” – is exactly what capitalism latches on to, like the great parasite it is, to feed its remorseless appetite for accumulation.

A habit of thought

Over 60 active years, against all odds, Jameson carved out one of the great unbroken adventures in unapologetic Marxist thinking in that howling wasteland of unchecked free enterprise we call the United States of America.

In one of his most eccentric undertakings, An American Utopia (2016), he imagined a communist seizure of the military apparatus via universal conscription and the withering away of the largest state in history. There was nothing that could not become grist to the dialectical mill of Jameson’s restless utopian thinking – even the nation whose partisan anti-intellectuals regularly named him as one of those dangerous “Marxist professors” we hear so much about.

Utopia was, for Jameson, more than a hope deferred or a crazy workbench covered with unfinished social blueprints. It was a habit of thought we cultivate among ourselves. He once claimed utopia to be the place where the problem of death was solved. For in utopia we discover the human totality, the great march of generations, from whose vantage point individual death becomes “a matter of limited concern, beyond all stoicism”.

It is from that bourn Jameson greets us. He calls us out of our tarpits of identity, compels us to reckon with the savage fates in store for us if we allow ourselves to be divided by those who have everything to gain from preventing the unrealised utopia we carry within us, like living spores.

Julian Murphet does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.