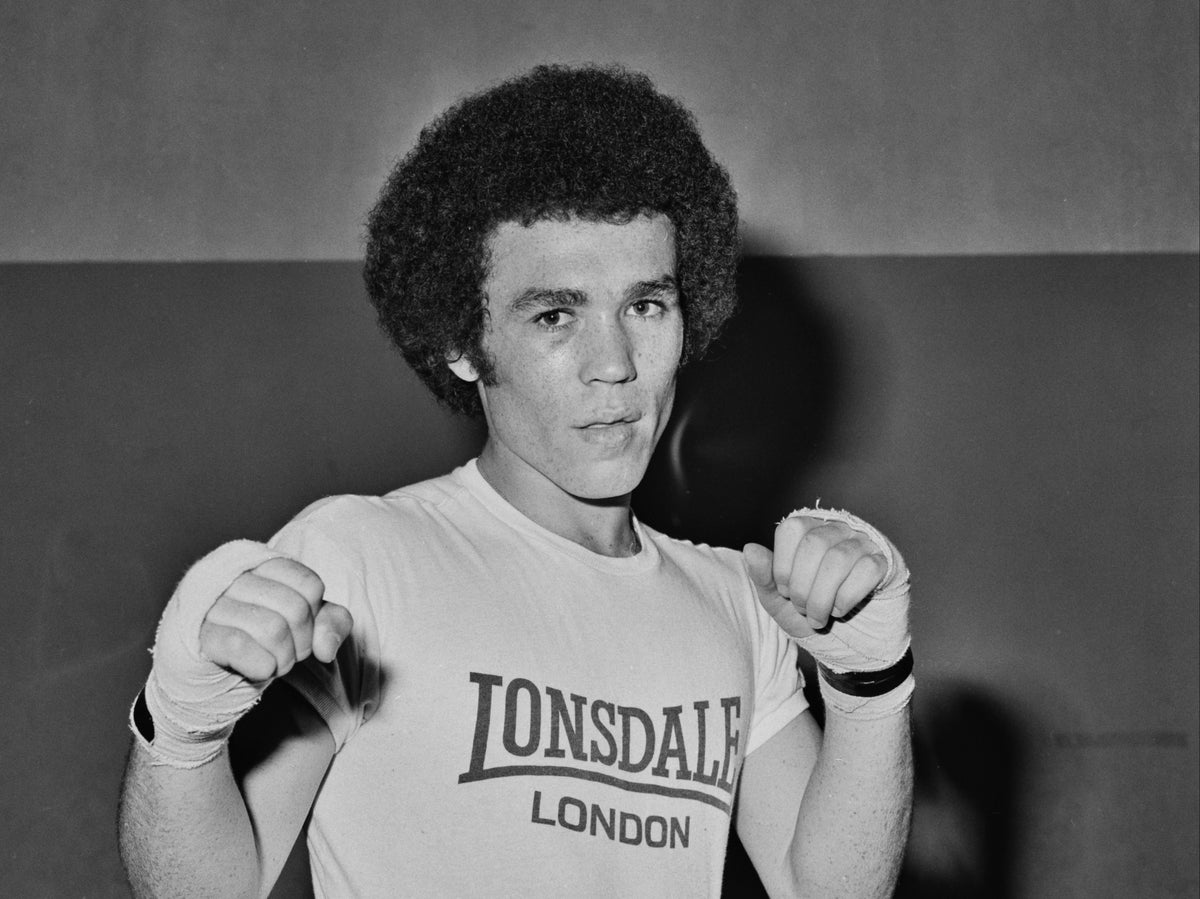

Frankie Lucas might just be the greatest boxer you have never heard of. His story is certainly one of the wildest boxing stories to be told. After almost 50 years, that story is coming to the stage and the long-forgotten fighter might just get a remarkable renaissance. He deserves it.

Once upon a time in a south London boxing gym, a ridiculous plan was hatched. There was no chance that the plan would work, trust me. Except it did, and it is the subject Going for Gold, a new play on a short run at the Chelsea Theatre in London this week.

It is a story of ring brilliance, ring ignorance, suffering, winning gold medals, a community united and a Rocky story that would make “Sly” Stallone weep.

Let me start with the facts and figures; this is not a tale for fans of decency in sport. Lucas was abused badly, not once but twice as an amateur boxer and then during his troubled professional career. In 1972, which was an Olympic year, Lucas beat a man called Alan Minter in the London Amateur Boxing Association middleweight championship. The win was on cuts, Frankie was a teenager, Minter was the favourite and the chosen one. Lucas went all the way to Wembley that year and won the national title. He was just 18, a dangerous boy.

Two months later, the selection for the Olympic squad took place. Minter was in and Lucas was out. In all fairness, Minter had some international experience and Lucas was raw. It was harsh, but not criminal. Minter won a bronze medal and won the hearts of a nation. Meanwhile, in Croydon, Lucas was back in the Sir Philip Game gym and getting ready for a new season and defending his ABA middleweight title. Minter had turned professional and would eventually win a world title in Las Vegas.

In 1973, Lucas was savage and in May retained his ABA title. In the final he beat Liverpool’s Carl Speare. He was sent to America for an international and he beat the best American at Madison Square Garden. He was sent to the European championships in Belgrade in the summer of 1973 and lost to imperious Soviet Vyacheslav Lemeshev in the quarter-finals. Lemeshev had won gold at the Olympics the previous year with four knockouts. Lucas pushed him. Lucas was still only 19 then, but he was seasoned by the end of 1973 – a double ABA champion, fearless, heavy-fisted. In 2023, he would be able to invent figures in talks with promoters. Not in 1973, sorry.

The Commonwealth Games in 1974 were being held in Christchurch, New Zealand, at the start of the year and that meant that Lucas would not be able to defend his ABA title. However, he would surely be sent to the Games as England’s middleweight. Surely, that was obvious. No, Carl Speare was selected. Lucas was rejected again; he was only a kid. What had he ever done to upset so many men in blazers?

And after that snub, the meeting takes place inside the Sir Philip Game gym. They wanted to somehow get their little Frankie to New Zealand. They were going for gold.

A man called Ken Rimington had an idea. Lucas had joined his mother in Croydon when he was a little boy. He had left St Vincent in the Caribbean to live in Croydon. He found the gym a few years later. Rimington picked up the phone in the committee room at the club and started making calls. This is all true.

A boxing association for St Vincent was formed. The Commonwealth Games organising committee accepted the new association and they accepted Lucas, a middleweight and still only 20. Time was running out, money was short. Fundraisers did a bit, but the Scottish Amateur Boxing Association came in with some help. Lucas helped their fighters prepare. Lucas was on his way. His coach from Croydon, Ray Chapman, was the now head coach for the new St Vincent and the Grenadines Amateur Boxing Association. That should be enough of a story, to tell the truth.

The tiny team landed in New Zealand. Lucas was the only member for St Vincent. He carried the flag at the opening ceremony. He ignored a pre-tournament function, hosted by Princess Anne. So what? He was there for glory, not bowing to a princess; Frankie Lucas was not big on bowing.

And then the fairytale started. This is magic and I remember it so, so well. Lucas was a hero in my house, he was a south London boy who refused to accept “no“ as an answer.

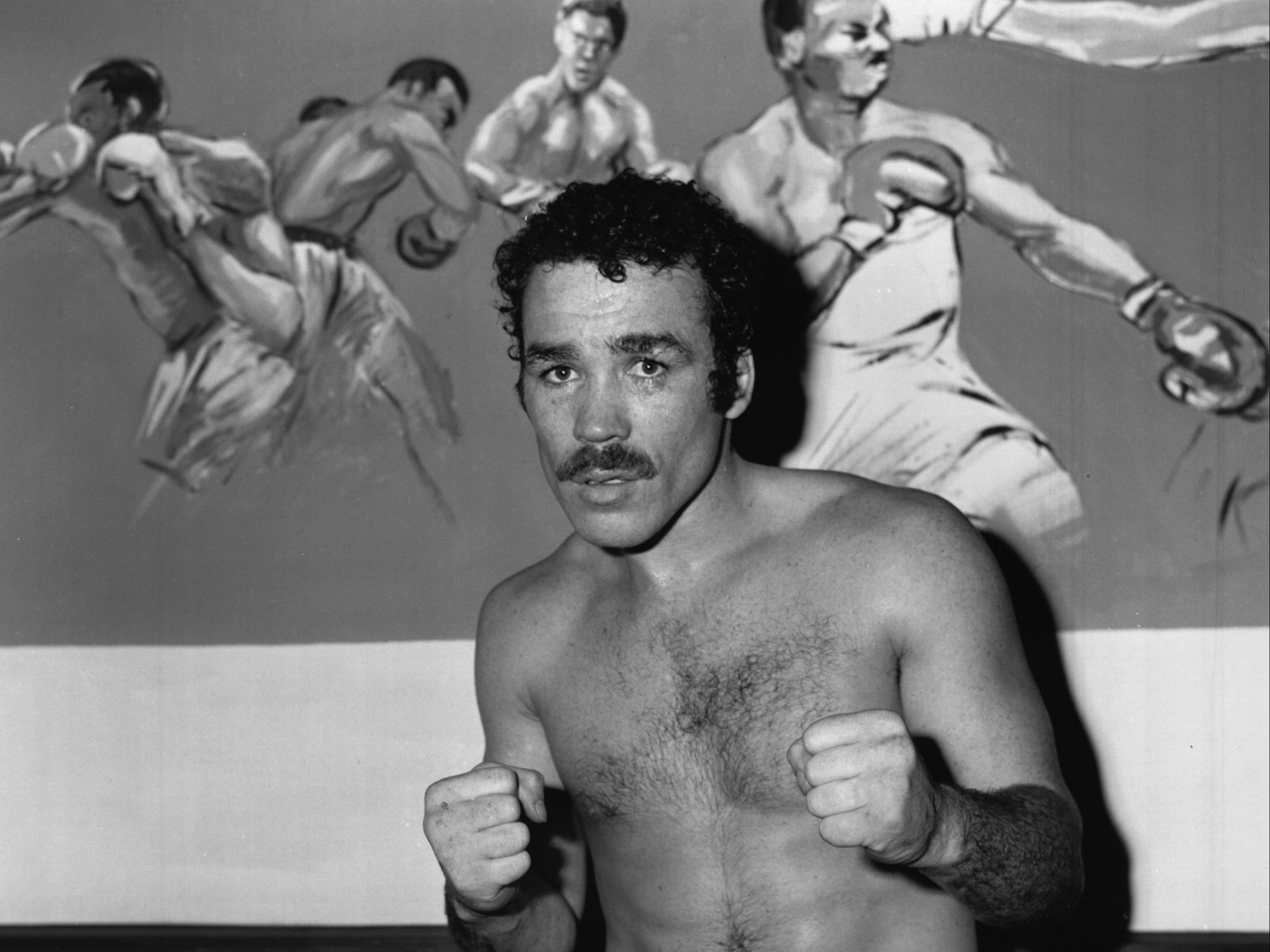

Carl Speare was in the draw, but the real danger was Julius Luipa from Zambia. He was trained by Cubans, he was lethal. I have spoken to people that were there and they painted an ominous picture; Lucas had no chance with either the judges or Luipa’s punches. However, nobody told Frankie that. Luipa knocked out two men and reached the semi-final. Lucas and Speare both won twice and met in the other semi. Lucas beat Speare on points, it was a form of justice. But he was in New Zealand for more than that. In the final, Luipa was brilliant. Lucas was wearing second-hand kit. Frankie was cut in the first round, and it was bad. Luipa went back to his Cuban corner smiling. Then, in the second round, Frankie Lucas the renegade went to war.

Luipa was knocked out. Bosh, that is the story. Lucas went for gold, and he got it. He turned pro and that was ugly. He had demons on both sides of the ropes. He could have been great. He lost two British title fights and then he went on the missing list. He was presumed dead.

Then he was found, living in care near his old pro gym in north London. He blessed this play, written by Rose Hollingsworth and starring her son, Jazz Lintott as Frankie. Rose met Frankie when she served him each day at a greengrocer’s shop at the end of the Seventies. Lucas had promised to attend the opening. In early April he died. His funeral was low-key; he will be served by this play and plans for bigger things. He deserves it.

Never doubt that dreams and fairytales take place in south London. Frankie Lucas is that fairytale, this play is his story.

‘Going for Gold’ is at The Chelsea Theatre from 5 to 8 June