Space travel – in all its forms – is problematic. Impossibly dangerous, hugely expensive, and politically fraught in a world crying out for better redistribution of wealth and resources. Space tourism, on the other hand, is an order of magnitude more contentious. You can take all these considerations and amplify them, as well as strip away any potential scientific benefits that might make for mitigating circumstances.

HALO Space wants to take people to the very edge of the atmosphere without the economic, social and environmental cost of building a big rocket. Space tourists have been few and far between, with a handful of big spenders risking it all to ride the Russian Soyuz to the International Space Station in the first decade of the century.

These pioneers were followed by the first passengers on the Virgin Galactic, with a clutch of space tourists boarding the Axiom Space missions that use Elon Musk’s SpaceX platform, seats that cost $55m each. There’s also Blue Origin’s New Shepard 4 ‘tourist’ spaceship, one arm of the company founded by Jeff Bezos. Other missions in the offing include American company Space Adventures’ plan to fly a group of paying passengers on a circumlunar journey.

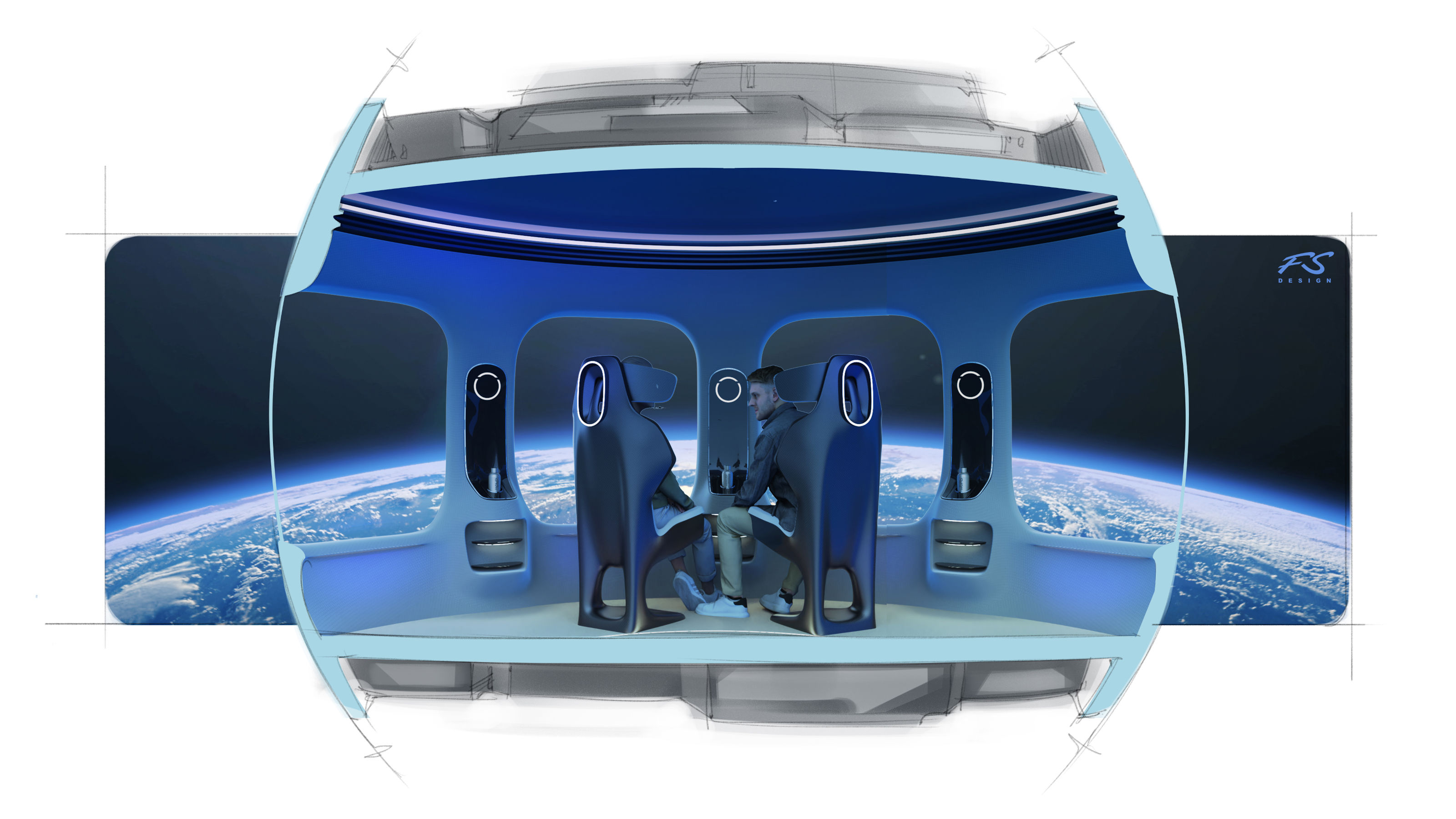

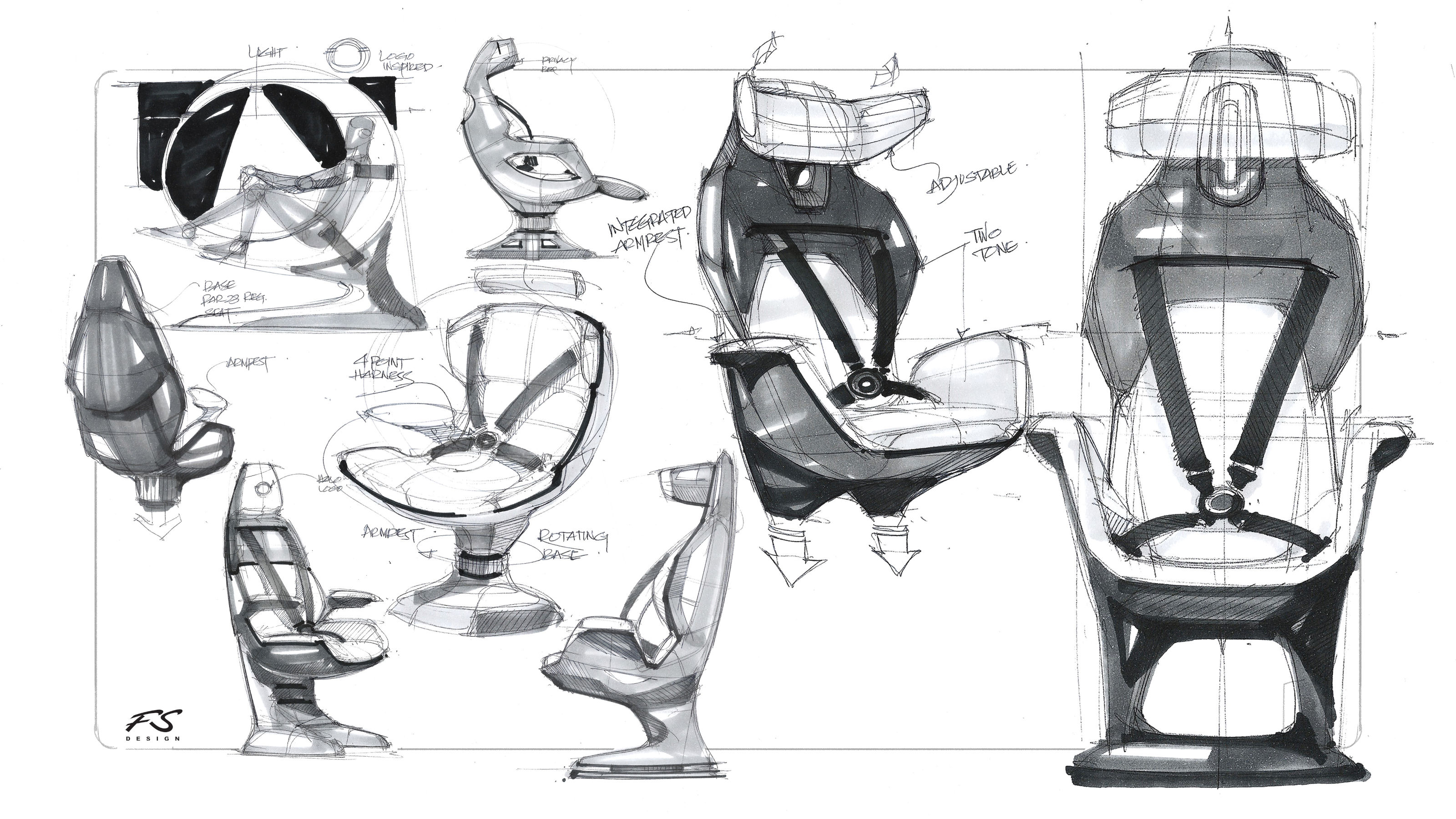

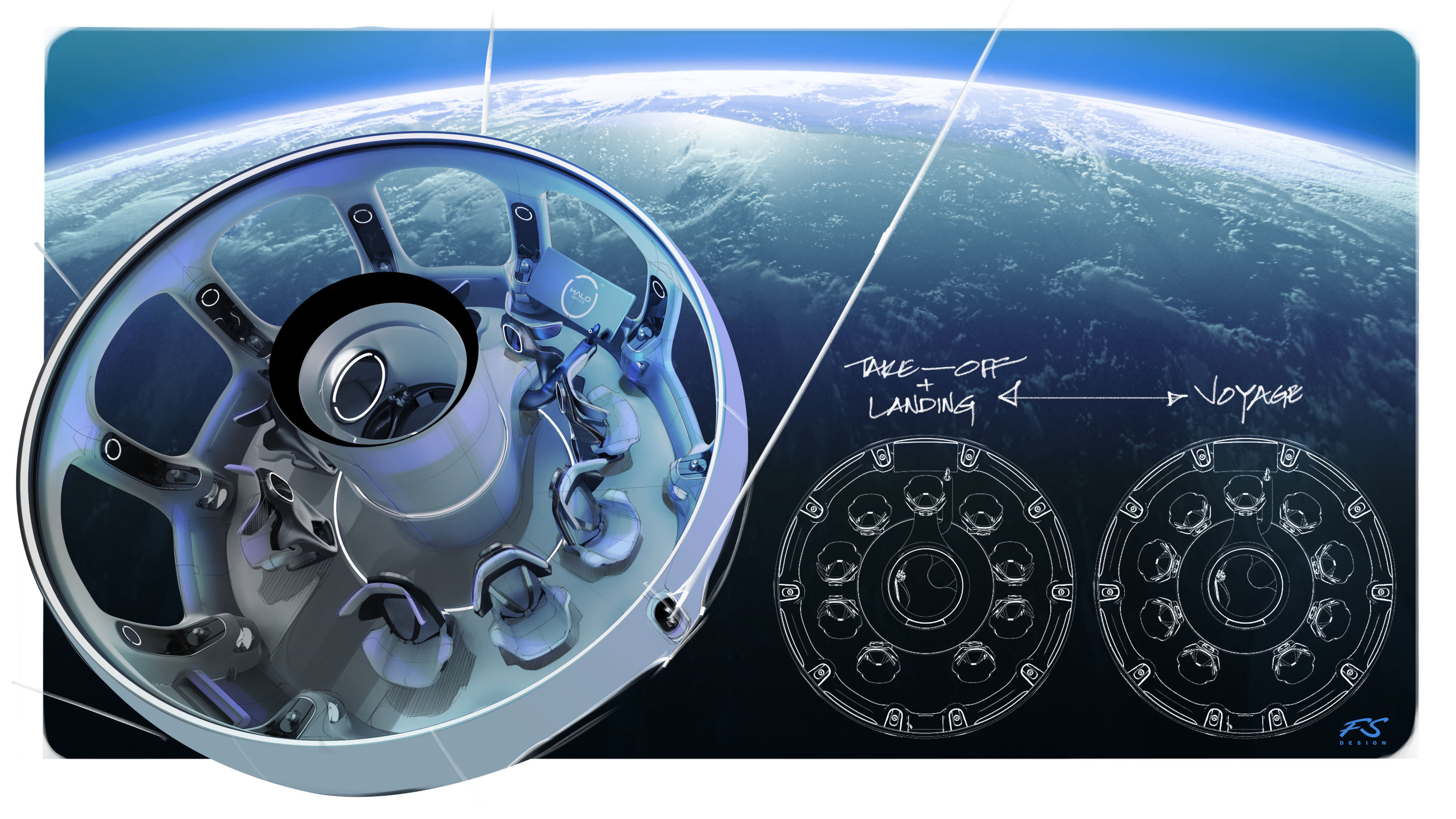

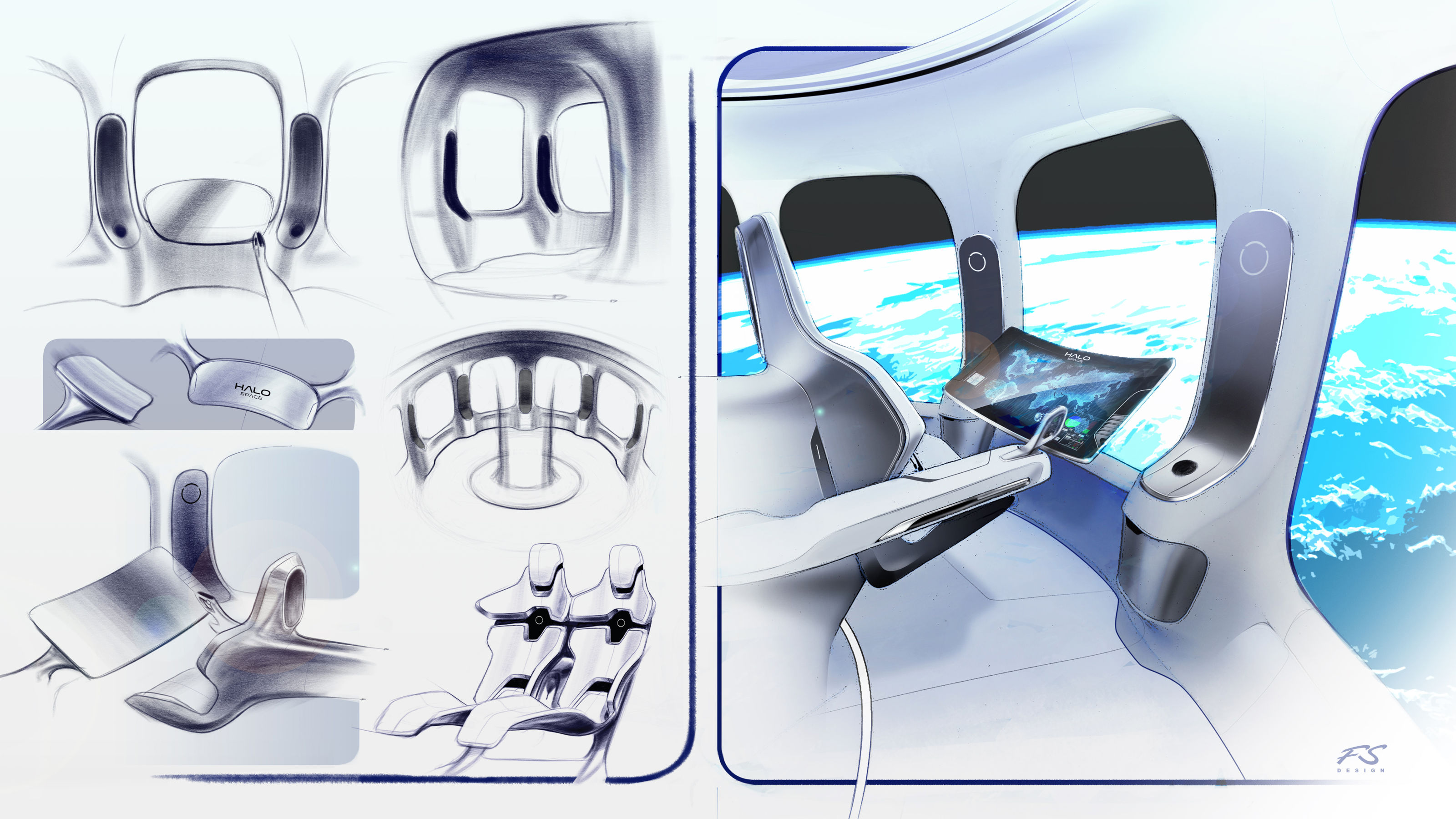

Frank Stephenson’s Aurora capsule for HALO Space

HALO is not like these companies. Founded in 2021, its ambition is to reach altitudes of between 25km and 35km using a stratospheric balloon. Up to eight passengers will be accommodated in a pressurised capsule, the Aurora, shown here in preliminary renders by Frank Stephenson Design. The method is zero-emission and substantially safer than a conventional launch, with the benefits of a longer mission time and a much better viewing experience.

HALO is not the first company to use this method; World View, Space Perspective and Stratoflight all promise a similar approach, although the last’s capsule detaches and glides back to Earth with the aid of a large parafoil wing. Stephenson – a former car designer for McLaren, Mini and Ferrari – runs a design consultancy that’s tackled electric aviation and child car seats, amongst many other things.

For HALO, Stephenson and his team have leant in hard to the cinematic and futuristic elements of the brief. With an interior dedicated solely to observation, not scientific investigation, the Aurora is an opportunity to prioritise comfort and aesthetic appeal, not just pure function. The long, languorous flight times created by the balloon’s gradual ascent mean there’s time and space to relax. Hence the array of chairs that look more Star Trek than space shuttle, and the 2.82 sq m of windows that’ll provide a panoramic view of the Earth’s curvature.

Overall, the Aurora capsule will have a take-off weight of 3,500kg, thanks to extensive use of composites and other lightweight materials. ‘Working on a project of this magnitude brings about many challenges from a design perspective,’ says Stephenson. ‘Crafting a beautiful interior for passengers while considering factors like strict safety regulations and weight distribution presented challenging hurdles; [we are] totally committed to offering a luxurious, aesthetic appeal with functionality. I am immensely proud of what we have achieved.’

Stephenson isn’t the first high-profile designer to find themselves boosted by the romance of space. Virgin Galactic’s Spaceport America in New Mexico was shaped by Foster & Partners, while Philippe Starck had a go at creating an orbital environment for Axiom Space. In 2007, Marc Newson conjured up a reusable Spaceplane concept for Astrium, and World View employed the transport design skills of PriestmanGoode for its proposed capsule. And let’s not forget Raymond Loewy’s consulting work for Nasa, that very image-aware organisation, back in the 1960s.

HALO Space, HaloSpaceflight.com

Frank Stephenson Design, FrankStephenson.com