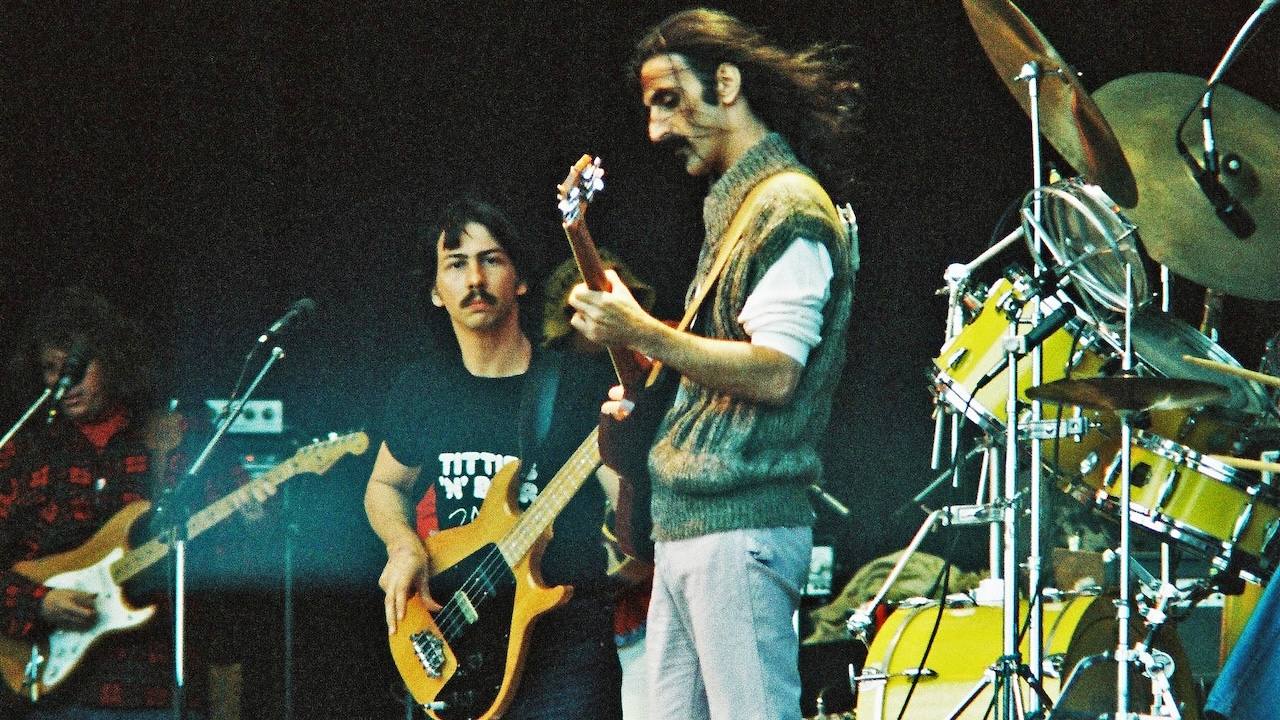

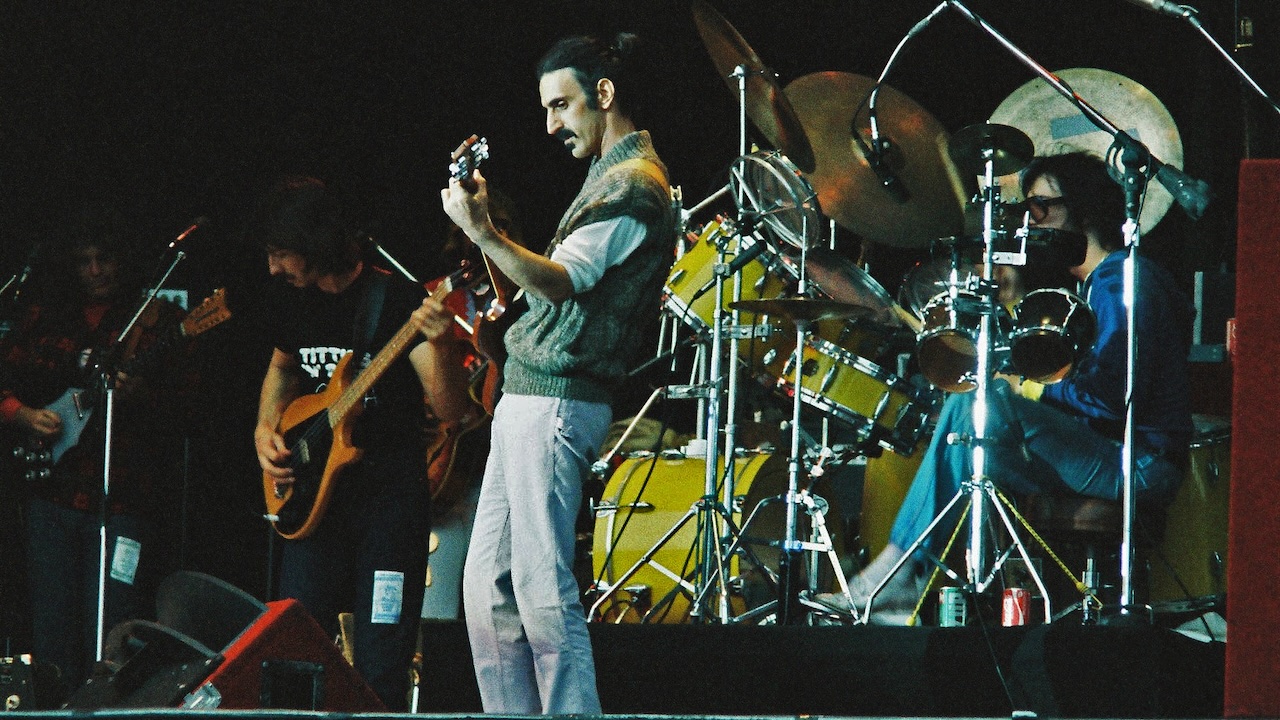

On June 15, 1978, Arthur Barrow underwent the audition for which he'd spent his whole life preparing. The North Texas State graduate had been given only two days to transcribe and perform a notoriously difficult unison line, one that no bassist had ever executed. But if anyone got a kick out of asking his musicians to do the impossible, it was Frank Zappa.

Barrow passed the audition and achieved one of the main goals he'd set for himself when moving to Los Angeles in 1975. In the process, he sparked a classic rearrangement of one of the maestro's signature compositions, St. Alfonzo's Pancake Breakfast from 1974s Apostrophe. It stands as one of the most terrifying unison lines ever performed by a bassist of any era, period.

“Frank asked me to transcribe the melody after I told him I'd learned Inca Roads by ear,” Barrow told Bass Player. “I can't say whether Frank was looking for someone who could do that, or maybe it was a challenge to see if I was bluffing!

“He would often adapt an arrangement to the abilities of the musicians in the band. The recorded versions were just snapshots of the way the songs were arranged at that time, but each song was constantly evolving, before and after they were released to the public.”

The new arrangement was immortalised by Zappa's 1978 touring band – which included a young Vinnie Colaiuta on drums – on the album You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore, Volume 1 as a part of the track Don't Eat the Yellow Snow. This rendition of St. Alfonzo's is faster than the original. It sounds almost atonal, with unusual interval jumps and a shape-shifting dissonance throughout.

But Barrow found some methodology to the madness. “If you look at the melody in small groups, say four to eight notes, you can almost always find a tonal center. It starts in B, Lydian. Then in the last six notes of bar 2, Zappa uses half-steps and 4ths as leading tones through a Bach-like diminished transition.

“The first eight notes of bar 3 are Db Lydian, or you can think of it as F natural minor. The last eight notes are in F major, and so on. If you can't make sense of it, then you just have to think in terms of patterns of intervals.”

There are several spots to watch out for: beats three and four of bar 3 (a double jump up), beat three of bar 4 (an open string followed by a big jump down), the middle of bar 5 (climbing up the D string), the first two beats of bar 6 (descending on the G string), and finally, one last open-string jump (bar 7, beat three) before you stay in 1st position for some crazy interval jumping.

Barrow's tips: start slow, be precise, and use the same fingerings every time before speeding it up. “Frank pushed his musicians as far as he could with musical challenges, so I found myself doing things that I never thought I could have done.

“It may have helped that I was playing a Gibson Ripper, which allowed me to use a pretty light touch. Having said all that, I also practiced a lot!”

Barrow summed it up with a little advice: “Practice your technique at home, but when you play for real, play with the abandon of a child who's picking up the bass guitar for the first time!”