Francis Bacon may still be widely regarded as the “greatest British artist of the 20th century”, but given we’re now nearly a quarter of the way into the next century, that hardly guarantees relevance. Bacon was a sadomasochistic, gay alcoholic who transgressed every boundary of petit-bourgeois propriety, but he’s still, at the end of the day, another dead white man. The mood of post-war angst he embodied so unnervingly now feels a very long time ago, and the tales of epic dissipation and nihilistic aphorisms have become boring through repetition.

A substantial Bacon exhibition is still a significant event, but it will have to work a lot harder to hold our attention in these culturally contested times than it would have even 10 years ago.

This exhibition – co-curated by writer Michael Peppiatt, author of one of the more entertaining Bacon memoirs – is the first to look at Bacon “through the lens of his fascination with animals”. That isn’t just “the animal”, the current of visceral physicality running through his work, but actual animals. Bacon paintings featuring monkeys, dogs and bulls spring immediately to mind, but it’s hard to imagine there are enough of them to sustain a large exhibition.

The show, however, argues that the artist, who grew up on an Irish stud farm, had an obsessive interest in “how animals fought, how they mated and how they died”, and that he was “convinced he could analyse humans more directly and tellingly by watching the way animals behave”.

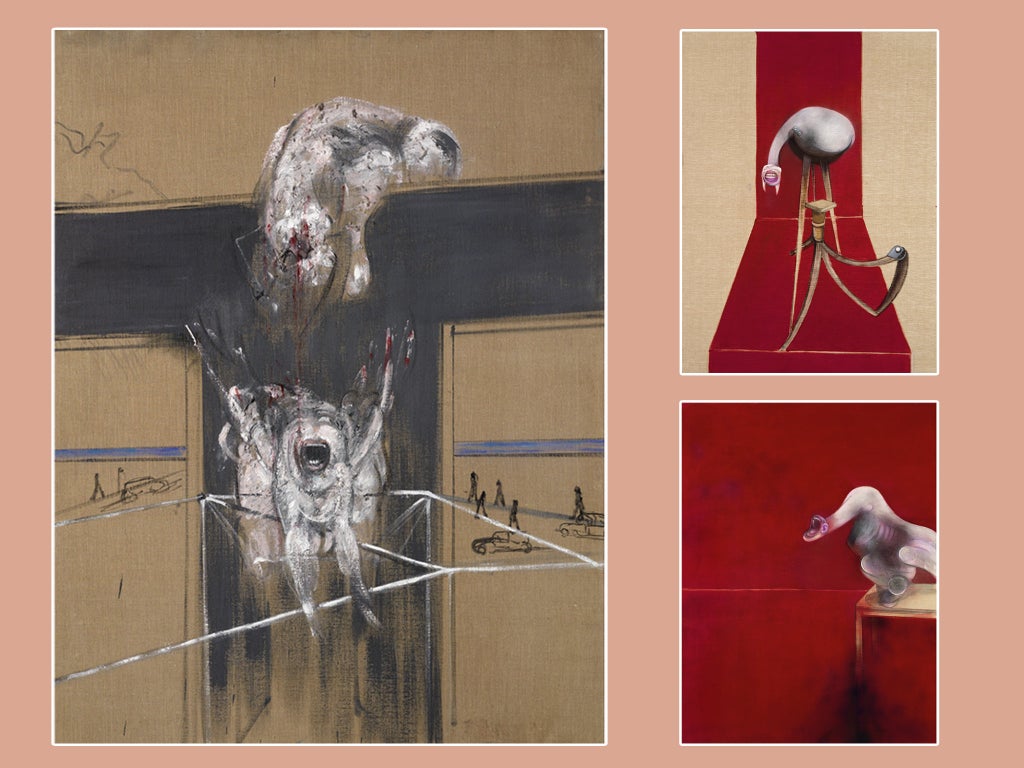

While Bacon’s studio was apparently crammed with “wildlife books”, his interpretation of animal form was hardly scientific. In the show’s opening painting Head I (1948), a male human head and a monkey’s ferocious bared teeth merge into one blurred form, with the alarming, and typically Baconesque, sense that aggressor and aggressed, the eater and the eaten, have become one.

In the next room, in an electrifying coup de theatre, we’re shown three very early paintings, from 1944-46, representing, the show claims, “furies” – ancient Greek deities of guilt and vengeance that the artist employed to “embody his own disquieting sensations and emotions”, but conjured through banal, modern objects. In Figure Study I, the presence of the figure is implied by a draped tweed overcoat and hat. In Figure Study II a howling eyeless figure emerges from the coat, while in Fury, the figure is reduced to a gaping, ravenous mouth on spindly limbs.

Whether or not these works, united by their brilliant orange backgrounds, and dramatically spotlit, were intended to be seen together as a sort of triptych, as they are here, the effect is stunning. This is a sort of post-Holocaust surrealism that still feels raw and challenging.

After this taste of early Bacon at his absolute best, the standard of works hardly dips in a large room devoted to “wildlife”, where we’re shown images of monkeys (a chimpanzee evoked in a blurred mass of paint marks stands out), dogs (including a famous image of an exhausted mastiff glimpsed by a roadside on the Cote d’Azur) and quite a number of naked men having messy, muscular sex.

While I’m prepared to be persuaded that the grassy settings of these latter paintings were inspired by sightings of animals passing through long, sunlit grass, which had “mesmerised” Bacon on a trip to South Africa, the show interprets his interlinked perceptions of the human and animal conditions so broadly, it becomes an excuse to include just about any Bacon work.

The portraiture section finds space for four of his seminal Pope paintings – only one of which includes animal imagery – on the grounds that he “strips away the pretensions of even the highest sections of society”, presumably to an “animal” essence (the wall texts veer frequently into specious pop psychology). But it’s hard to complain too bitterly when faced with works of the quality of Study from Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1965), Head VI (1949) and Pope I (1951), all inspired by a great Velasquez portrait with which Bacon remained obsessed for decades.

Bacon perceives a current of violence and cruelty not only in Velasquez’s image, but in the whole process of the containment and scrutiny of the human form: two of his popes are contained in cage-like structures; one howls in anguish or agony. The quintessential Bacon questions of whether he’s aghast at that cruelty or simply enjoying it, of whether the violence of his brush marks is spontaneous or highly calculated – issues that might have become tired over the decades – still feel fresh and immediate.

This, then, is a sound trawl through Bacon’s career, with an often vaguely applied animal theme: are the smeary figures in a room on “The Animalistic Nude” any more “animalistic” than those in other Bacon paintings – if that’s even a proper word? With most works being from British collections, and many frequently exhibited, there will be few revelations for the seasoned Bacon-fancier. Yet it provides a compelling and welcome reminder of why he is still an extremely important artist.

If the quality of the work falls off in the second half of the show, that is simply an accurate reflection of Bacon’s trajectory. Where some artists, such as Picasso, one of Bacon’s great early inspirations, were able to endlessly vary and extend their output, Bacon went on refining the signature tropes developed early in his career.

The blurring and deconstructing effect he derived from long-exposure photography, which makes his subjects look as though they’re being sliced apart in front of us – seen to powerful effect in Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne (1966) – has become a mere stylistic mannerism by the time we get to Two Studies of the Human Body (1974-75), with its naked athletes derived from the anatomical photography of Eadweard Muybridge. The manipulation of paint is virtuosic, but the distortions lack real conviction.

A trio of bullfighting paintings from 1969 give a superficial impression of power and energy, though by this point in his career he has that “Bacon look” down pat. The sense of rawness and discovery, of being at the limit of what’s possible, felt in the show’s first few rooms, has ebbed away over the decades.

Yet even at this late stage, Bacon could still evoke a sense of truly hair-raising moral disquiet. In Triptych August 1972, we see three naked images of Bacon’s lover George Dyer, who had killed himself the previous year on the eve of Bacon’s major retrospective – the crowning moment of his career to date – at Paris’s Grand Palais. With Dyer appearing variously to melt onto the floor, reduced to a heap of redundant flesh, or with parts of his body sliced and carved away against the black background, the painting appears to be both an homage to one of the great loves of Bacon’s life and a kind of murder in paint.

At such moments, we feel ourselves at Bacon’s shoulder, staring into the moral abyss in a way that feels both terrifying and exhilarating. It is that feeling of unflinching ambiguity that will make this exhibition feel peculiarly relevant to our current uncertain times.