Sir David Attenborough has said he is “truly delighted” after scientists named the fossil of the earliest known animal predator after him.

The fossil is the first of its kind and is believed to be the earliest creature to have a skeleton, scientists say.

The 560-million-year-old specimen, which has been named Auroralumina attenbouroughii, was found in Charnwood Forest near Leicester, where the rocks date back 600 million years.

The 96-year-old used to go fossil hunting in the area, which was once considered too old to contain any fossils, and is credited with raising awareness of Ediacaran fossils in the forest.

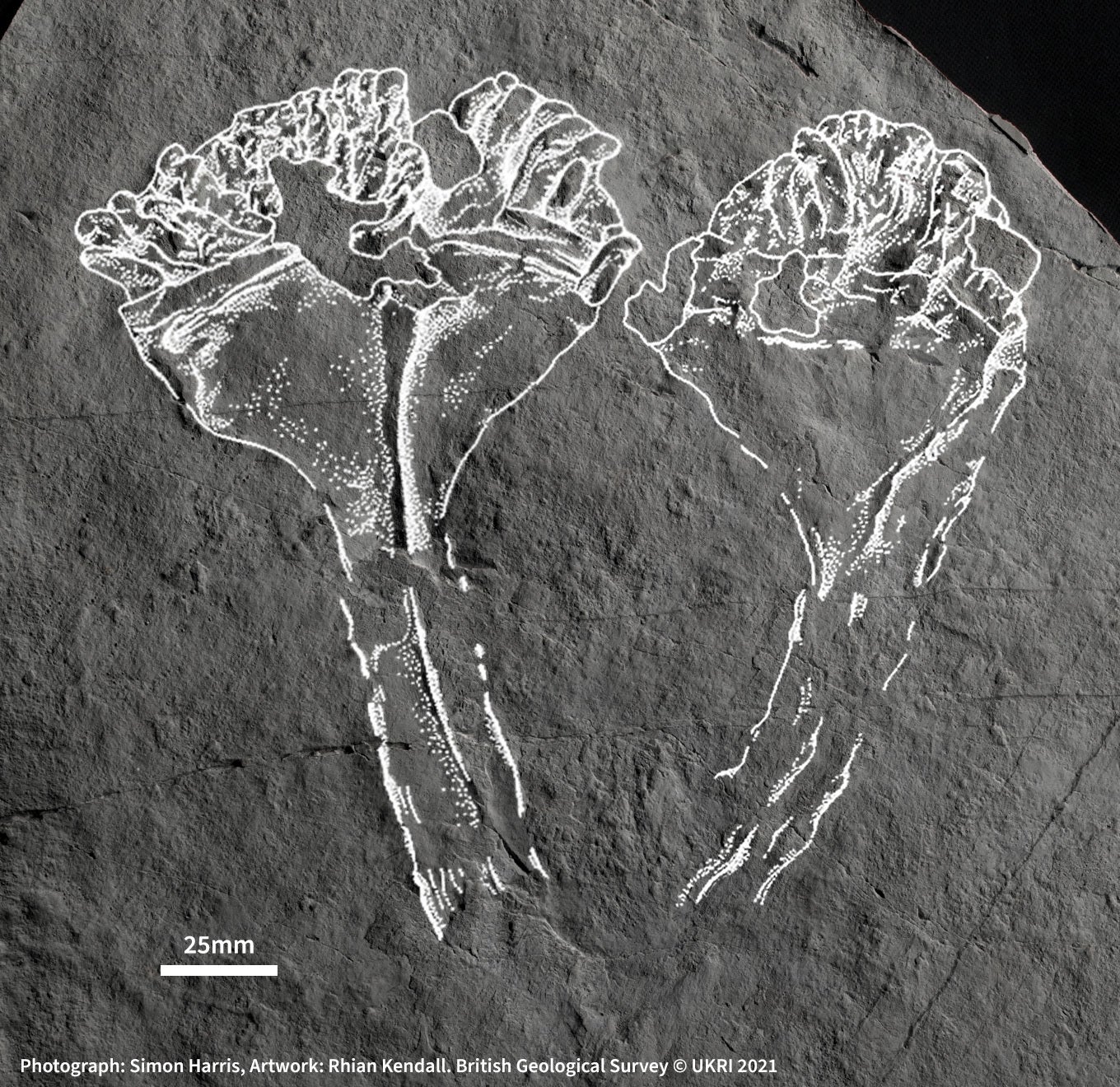

The first part of the fossil’s name is Latin for “dawn lantern”, in recognition of its great age and resemblance to a burning torch, according to a report in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Upon the recognition, Sir David said: “When I was at school in Leicester I was an ardent fossil hunter.

“The rocks in which Auroralumina has now been discovered were then considered to be so ancient that they dated from long before life began on the planet.

“So I never looked for fossils there. A few years later a boy from my school found one and proved the experts wrong.

“He was rewarded by his name being given to his discovery. Now I have – almost – caught up with him and I am truly delighted.”

The specimen was found in 1957 by Roger Mason, after whom Charnia masoni was named.

Dr Phil Wilby, palaeontology leader at the British Geological Survey, is one of the scientists who made the discovery.

He said: “It’s generally held that modern animal groups like jellyfish appeared 540 million years ago in the Cambrian explosion.

“But this predator predates that by 20 million years. It’s the earliest creature we know of to have a skeleton.

“So far we’ve only found one, but it’s massively exciting to know there must be others out there, holding the key to when complex life began on Earth.”

In 2007, Dr Wilby and his team spent more than a week cleaning a 100 metre square rock surface with toothbrushes and pressure jets.

In a rubber mould of the entire surface, they found more than 1,000 fossils – and one in particular stood out.

Dr Frankie Dunn from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, said: “This is very different to the other fossils in Charnwood Forest and around the world.

“Most other fossils from this time have extinct body plans and it’s not clear how they are related to living animals.

“This one clearly has a skeleton, with densely-packed tentacles that would have waved around in the water capturing passing food, much like corals and sea anemones do today.

“It’s nothing like anything else we’ve found in the fossil record at the time.”