This article was originally published on 19 October 2018

When Big Brother was axed this year, it seemed it could simply no longer compete in the salacious stakes with the copycat shows that came in its wake. What good was a reality show where contestants sit around in a rainy English house discussing their grocery budget, when its younger cousin, Love Island, has chiselled singles sending each other into fits of lust-induced paranoia in a Mediterranean villa?

Indeed, reality TV of the “people forced to live in maddening proximity” ilk has grown gradually more emotionally and sexually intense over the past 20 years. And yet it still has some catching up to do with what in many ways was paradoxically its precursor: a sociological experiment conducted at sea in 1973.

Originally dubbed a “peace project” but soon rechristened a “sex raft” by the world’s press, The Acali Experiment saw five men and six women of various religions, nationalities and social backgrounds drift across the Atlantic on a raft for 101 days. It wasn’t televised – there was barely enough room to swing a cat on the Acali, much less have it stage a live broadcast – but eight hours of 16mm camera footage were taken on board by its architect, Santiago Genovés, which have been used by director Marcus Lindeen in a new documentary, The Raft.

“By chance, I read a German scientific book about the 100 strangest scientific experiments of all time, and one of them was called ‘The sex raft’, about the Acali experiment,” Lindeen told Nordisk Film & TV Fond of the project’s inception. “I started digging into the subject and found out that the captain of the raft was a female Swedish captain, which intrigued me even more. I quickly realised it was a fabulous adventure story.”

Santiago Genovés, a Mexican anthropologist with a God complex, died in 2013 not long after Lindeen had begun his research. “His son very generously invited me to come to Mexico to go through his father’s archives,” said the filmmaker, who tells much of the story through the detailed diary Genovés kept. “I was lucky enough to be hijacked on a plane to Cuba,” writes Genovés, of the real-life experience that began his fascination with what pushes people to violence. In retrospect, this maniacal admission is a red flag. While reality TV shows-cum-social-experiments tend to be disingenuous about their aims, the producers acting surprised (but secretly delighted) when contestants pair off or square off, Genovés speaks plainly of his hopes for sexual and aggressive behaviour.

“I have selected participants who are sexually attractive, and placed among them a Catholic priest,” he explains. In order to further “create tension”, several of the participants chosen are married, and women are given the more important roles on the vessel. “Can we live without war?” is the lofty, overarching question Genovés seeks to answer with his experiment – which takes place while the Vietnam War rages on – but the impression The Raft conveys is more of a man who simply enjoys pushing people’s buttons.

Lindeen reunited the surviving members of the Acali for his film. “It was quite difficult as I didn’t have their real names,” he recalled. “Santiago had used pseudonyms in the research papers, so it took almost two years to find the seven surviving members.” Spliced together with the footage, Lindeen has them recall their experiences from a wooden replica of the raft. With no books, no space and no escape, they can only sing songs and tell stories to entertain themselves. They do so quite happily for the most part, until day 22, when boredom sets in. By week four, several people were having sex. Asked how many people they slept with while at sea, one participant replies with a laugh: “Many, many... Everybody.”

“It was complicated to have sex on the raft,” they explain, and it usually took place between the two people who were on guard while the others slept. Coordination and dexterity were key: “You had to use one of your hands for steering.”

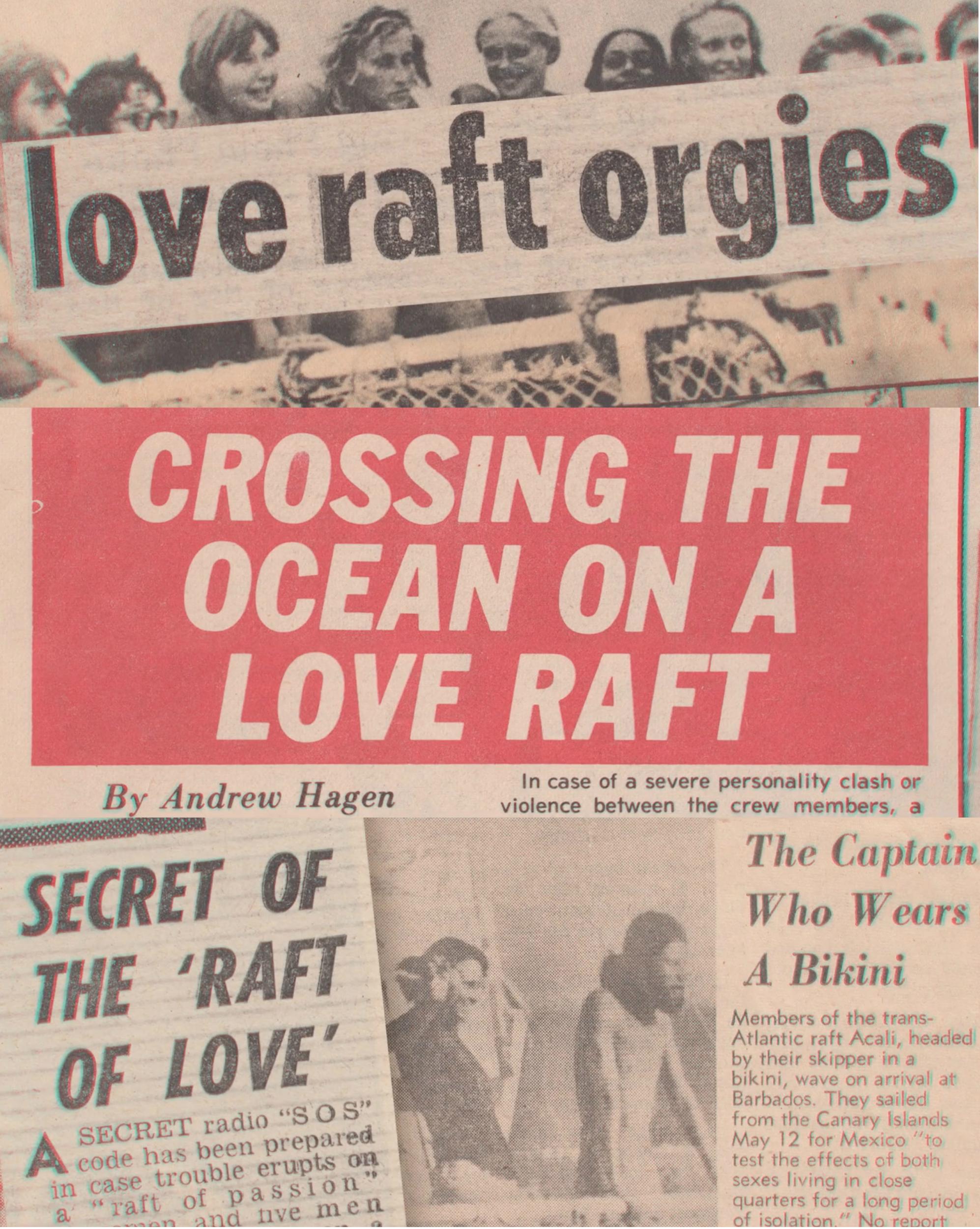

In the press, the Acali was not making the kind of waves anthropologist Genovés had hoped. “Secret of the ‘raft of love’” one tabloid headline at the time read, the news story opening on the “secret radio ‘SOS’ code [that] has been prepared in case trouble erupts on the ‘raft of passion’”. A second column was devoted to the fact that the captain wore a bikini.

“The press at the time had written a lot of dirt about the expedition, calling it a ‘Sex raft’ which wasn’t quite true,” Lindeen said. “Yes, a few people had sex, but it was nowhere near the orgy described in the tabloid press. When the women returned ashore, they were shocked by the media coverage.”

Genovés may have been hoping for a more serious treatment of his experiment, but sex among his subjects was indeed what he wanted to see. Before long, his appetite for blood has also been met. A small shark is hauled onto the raft and senselessly hacked to death. One excitable crew member wields the axe like a hammer, before excavating the shark’s still beating heart and holding it up.

Yet it soon becomes clear The Raft is not a story of how sex and savagery will always materialise when a group of humans are left alone, but an account of one man’s egotism. The participants’ sexual interactions prove to be innocuous, their instances of aggression isolated and small, and they generally function quite well as a micro-society. This displeases Genovés who, in a bid to stir things up, reads out the responses his subjects thought they had given him in confidence to some very personal questions. “Who would you most want to have sex with?” and “Who would you want to kick off the raft?” are some examples – prefiguring a tactic which, it should be noted, has become a core feature of Love Island.

With Genovés throwing buckets of water on people and employing “Gestapo methods”, the participants became furious that their guide had become their dictator. A turning point comes when the anthropologist stages a coup against the raft’s captain, the very same female leader he installed in order to observe how the men on board would react. This is the documentary’s most impressive moment, as the participants recall very matter-of-factly how they one night conspired to kill the man who had brought them together. One idea was to have him take a convenient tumble overboard, another involved a syringe, with every crew member holding the needle to assure their collective culpability, and therefore silence. Unsurprisingly, this night-time conspiracy on the roof of the raft wasn’t captured on camera, but the filmmakers manage to get the would-be murderers to recount it frankly from the reconstructed roof. “I’m happy that no one was killed,” calmly concludes Eisuke Yamaki, who was pegged to push the offender overboard.

Remarkably, the Acali makes it to the shores of Mexico after 101 days with only piscine blood having been spilled. The group solve their Genovés problem with diplomacy instead of violence, and are all the stronger and closer for it.

It’s precisely this bond that the documentary captures, offering a persuasive corrective to the “sex raft” narrative beloved of the tabloids, which had been based on their limited radio contact with the vessel. The participants, who elected to be part of the experiment on a whim, weathered the ordeal extraordinarily well. Though their scientist outrageously abandoned his duty of care, they don’t see themselves as victims. In this forerunner to the phenomenon of reality TV, no one was voted off and no-one left of their own accord. In fact, counter to what Genovés so clearly hoped for – everyone on board seems to have had a, for the most part, formative, peaceable time. Echoing what he said moments after stepping off the raft after three months, Servane Zanotti, recalls: “I could have gone for another three”.

Maybe another three months – a second season of sorts – would find an audience today. “It’s impossible not to think of reality TV,” Lindeen freely admitted when once asked whether he saw Genovés as a forerunner of the genre, noting that Mexican TV had in fact part-financed the project.

“The idea was to do a kind of scientific documentary series about the experiment. When Genovés was interviewed later in his life, he was asked if he saw himself as a pioneer of reality TV. He didn’t like it as he saw himself as a serious scientist.

“I mean, he was genuinely interested in researching human behaviour and to bring peace by understanding the origin of violence. But he was also a poet. He wanted science to be more like art. More experimental and daring.”

This is evident in the documentary, which gives a qualitative account of the adventure, and doesn’t find much worth reporting from Genovés data, meticulous though it was, with the Mexican charting subjects’ moods against wave patterns, moon cycles and countless other variables. As Lindeen concluded: “Perhaps the Acali experiment would have been more successful as an artistic rather than a scientific venture.”

The Raft premiered at London Film Festival and will open in UK cinemas on 18 January 2019