The government of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has just reached 100 days, a time to assess its performance.

Looking at foreign policy, the question is whether there has been continuity or change from the policies of prior governments. The correct answer is usually both.

Commentators will rightly say there has been great continuity on international policy with no revolutionary change in direction. As Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong recently said,

I have made clear that our national interests, our strategic policy settings haven’t changed – but obviously the government has, and how the government approaches engaging with the world and articulating those interests has changed.

So where can we see this change?

Increased international engagement

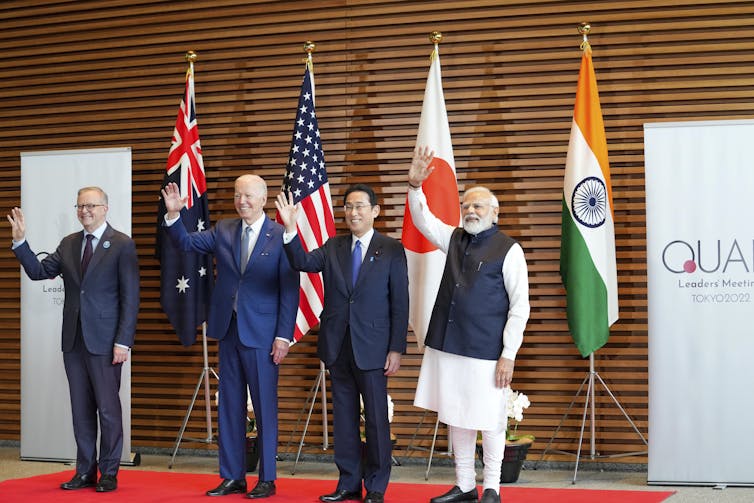

The first change is in the simple volume of international engagement. The day after he was sworn in, Albanese was in Tokyo for the Quad Leaders’ Summit, quickly followed by his first bilateral visit to Indonesia.

Wong has made four separate trips to the Pacific (Fiji, Samoa and Tonga, New Zealand and Solomon Islands, as well as July’s Pacific Islands Forum Summit) and three to Southeast Asia (Vietnam and Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia twice).

Minister for Defence Richard Marles has visited Singapore, India, the United States and the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Rwanda. And Minister for Trade Don Farrell was busy in Geneva with the WTO Ministerial Conference and bilateral meetings.

Some of this activity is due to the fortuitous timing of international meetings, but the rest is a conscious choice to prioritise international engagement. It suggests a certain amount of pent-up energy among new ministers with much on their agendas after so long in opposition.

The overall impression is of a government focused on international matters, which has perhaps adopted the mindset that external policy is as important as domestic policy. Albanese defended his trip to the NATO summit and Ukraine saying,

we can’t separate international events from their impact on Australia and Australians.

Resetting key relationships

The second change is a reset in some key relationships. Every new government should use the opportunity to get rid of barnacles that have attached themselves to the ship of state.

This was most notable in the reset in relations with France, still seething from the cancellation of its submarine construction deal in favour of AUKUS, the trilateral security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The diplomatic freeze with China was broken by the two ministers for defence meeting at the Shangri-La Dialogue and the ministers for foreign affairs meeting soon after. This was presented as “stabilising the relationship”, with the government stressing that there has been no change in policy position.

Changes in climate, Pacific and South-East Asia

Third, there has been a substantive policy change on climate action. This has had an impact on Australia’s international relations, particularly in the Pacific, where there had been no secret about Pacific leaders’ disappointment in Australia’s lack of climate ambition.

Only four days after being sworn in, Wong spoke to the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat to herald “a new era in Australian engagement in the Pacific” based on standing “shoulder to shoulder with our Pacific family” in response to the climate crisis.

Pacific leaders including the prime ministers of Samoa and Tonga welcomed this policy shift. While it won’t all be plain sailing ahead – with Australia likely to continue to face pressure around the speed of its transition away from fossil fuels – relations are much more positive.

Fourth, there has been a change in tone on some issues. For example, in South-east Asia former Prime Minister Morrison’s framing around an “arc of autocracies” was viewed as proposing a binary choice between democratic and authoritarian blocs. The Albanese government’s messaging emphasises “strategic equilibrium” where “countries are not forced to choose but can make their own sovereign choices, including about their alignments and partnerships”.

Increasing Australia’s international capability

Finally, the government is beginning the hard work of increasing Australia’s international capability across all tools of statecraft. It has announced a Defence Strategic Review and is updating its International Development Policy.

Read more: Diplomacy is essential to a peaceful world, so why did DFAT's funding go backwards in the budget?

The government has also committed to building the capability of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade after decades of declining funding. Allan Gyngell, National President of the Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA), sees this as a significant change:

“After years of marginalisation, foreign policy has been restored to a more central part of Australian statecraft.”

Long-term goals

Overall, after the flurry of early visits, the Albanese government gives the impression of a government settling in for the long-term.

Looking back on nine years of the previous government – with three prime ministers creating a sense of constant campaign mode – domestic politics often seemed to dominate. The new government gives the impression it is building relationships for the long-term – three, six or more years.

In its first frenetic days, the Albanese government took the opportunity to reset some key relationships. Now it’s all about steadily building these relationships and the capability to enable Australia to pursue its national interests in the long-term.

Melissa Conley Tyler is Executive Director of the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue (AP4D), a platform for collaboration between the development, diplomacy and defence communities. It receives funding from the Australian Civil-Military Centre and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.