On the verge of the 2024 elections, Donald Trump and Kamala Harris are ramping up their campaigns in Arizona and Nevada. Beyond being considered swing states, the two have something else in common: Latter-day Saint voters.

About 5% to 10% of Arizonans and Nevadans belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – among the highest percentages in the country, outside of Utah and Idaho. For decades, a steep majority of Latter-day Saints, often called Mormons, were regarded as reliable Republican voters. But the Trump era has tested that alliance, especially when it comes to many of his backers’ support for Christian nationalism.

Christian nationalism is often described as the belief that American identity and Christianity are deeply intertwined and, therefore, the U.S. government should promote Christian-based values. Using questions such as whether “being Christian is an important part of being truly American,” a Public Religion Research Institute poll in 2024 found that about 4 in 10 Latter-day Saints nationwide are at least sympathetic to Christian nationalist ideas, if not clear “adherents.” This was the third-highest rate among religious groups, behind white evangelicals and Hispanic Protestants.

Yet the report also found a seeming contradiction. Utah, home to the church’s headquarters, “is the only red state in which support for Christian nationalism falls below the national average.”

As a scholar of Mormonism and nationalism, I believe the church’s history and beliefs help explain why so many members wrestle with Christian nationalist ideas – and that this complexity illustrates the difficulty of defining Christian nationalism in the first place. America is sacred in Latter-day Saint doctrine: both the land itself and its constitutional structures. But as a minority that has often faced discrimination from other Christians, the church displays profound skepticism about combining religion and state.

Sacred space

The Book of Mormon – one of the church’s key scriptures, alongside the Bible – describes the Americas as “choice above all other lands” and provides an account of Jesus Christ visiting ancient civilizations there after his resurrection.

In addition, Latter-day Saint doctrine considers the United States’ government to be divinely inspired. In 1833 the church’s founder, Joseph Smith, dictated a revelation wherein God declared “I established the Constitution of this land, by the hands of wise men whom I raised up for this very purpose.”

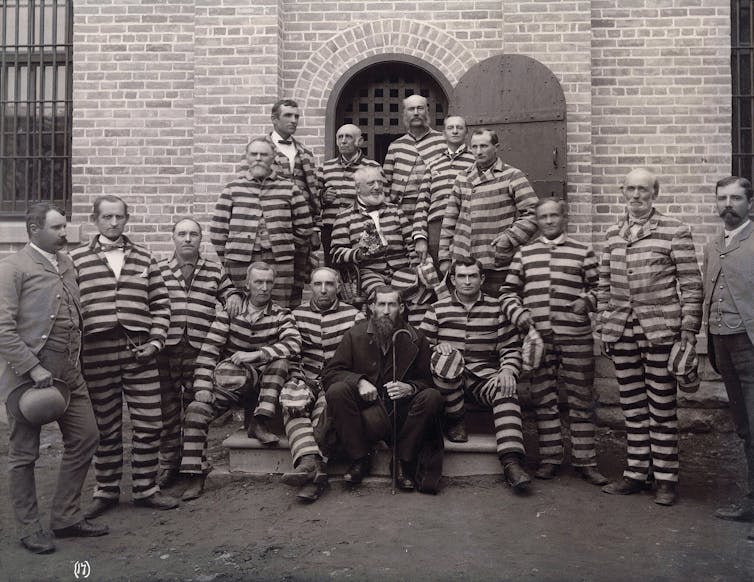

In the 1830s, Latter-day Saints migrated from New York and Ohio to western Missouri, where they believed themselves divinely commanded to build a sacred city called Zion. By the end of the decade, however, they had been forced out of Missouri by mob violence and an order from the governor, who called for the group to be “exterminated or driven from the State.”

Church members fled to neighboring Illinois, then began a long trek west after Smith’s death in 1844. The first pioneers reached Utah Territory in 1847, where they set up a society shaped by their beliefs – including, most famously, the practice of plural marriage. But when Utah applied for statehood, tensions with the federal government mounted.

Congress enacted anti-polygamy legislation that seized some church property, imprisoned more than 1,000 church members, disenfranchised anyone who supported the practice, and revoked Utah’s 1870 decision to give women the right to vote.

By 1896, church leaders had begun the process of ending plural marriage, and Utah was admitted to the union. Latter-day Saints also adopted the two-party system and embraced free-market capitalism, giving up their more insular and communal system – adapting to dominant ideas of what it meant to be properly American.

Constitutional patriots

These experiences tested Latter-day Saints’ faith in the U.S. government – particularly its failure to intervene as members were forced out of Missouri and Illinois. Nevertheless, church doctrine emphasizes duty to one’s country. One of the church’s 13 Articles of Faith explains that “we believe in being subject to kings, presidents, rulers, and magistrates, and in obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law.”

Latter-day Saints have “a unique responsibility to uphold and defend the United States Constitution and principles of constitutionalism,” as Dallin H. Oaks, a member of the church’s highest governing body, said in 2021.

I would argue that beliefs in the country’s divine purpose and potential, and the close relationship between faith and patriotism, may illuminate Latter-day Saint sympathy for Christian nationalist ideas. Yet the church’s previously fraught relations with the federal government, and with wider American culture, help explain why a majority of Latter-day Saints remain skeptical of Christian nationalism.

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, hostility against the church was so high and widespread that if the U.S. had declared itself a Christian nation, Latter-day Saints would likely have been excluded – and around one-third of Americans still do not consider them “Christian.” According to a 2023 Pew survey, only 15% of Americans say they have a favorable impression of Latter-day Saints, while 25% report unfavorable views.

Latter-day Saint leaders believe they have a right to exert moral influence on public policy. But the church’s awareness of its own precarious position in U.S. culture has made it wary of policies that put some people’s religious freedom above others.

A step too far

This wariness has also shaped Latter-day Saint culture’s inclination to avoid extremes. After decades of being marginalized for practices considered radical, the modern church and its adherents have walked a delicate tightrope. And for many, Christian nationalism and the candidate many adherents put their hope in – Donald Trump – seem a step too far.

Over the past half-century, Latter-day Saints tended to align politically and culturally with conservative Catholics and evangelicals. On balance, the church remains highly conservative on social issues, especially gender and sexuality, and 70% of its American members lean Republican. However, more younger Latter-day Saints have much more progressive views – and even the leadership has parted ways with the GOP on some issues, such as strict immigration proposals. While the church opposes “elective abortion,” it allows for several exceptions.

During the 2016 election, only about half of the church’s members voted for Trump; 15% voted for Evan McMullin, a Latter-day Saint who positioned himself as a moderate choice between Trump and Hillary Clinton. In 2020, Trump garnered about 7 in 10 Latter-day Saint votes.

During congressional hearings about the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, Arizona House Speaker Russell “Rusty” Bowers, who resisted pressure from the Trump administration to recall the state’s electors, cited his Latter-day Saint beliefs. “It is a tenet of my faith that the Constitution is divinely inspired,” Bowers said, explaining his refusal to go along with the scheme.

In June 2023, church leaders issued a statement against straight-ticket voting, saying “voting based on ‘tradition’ without careful study of candidates and their positions on important issues is a threat to democracy.”

Holy purpose

Ever since the Puritans, many people in what became the United States have believed God has a special plan for their society – part of the same current that drives Christian nationalism today.

Latter-day Saints, however, have a specific vision of that plan. According to the church’s teachings and scriptures, the country’s establishment was a necessary step toward restoring the “only true and living church” – their own. And that church is a global one, not just American. More than half of all Latter-day Saints today live outside the U.S.

Ultimately, Latter-day Saint teachings consider America’s story part of a greater goal: ushering in the second coming of Jesus Christ. As the church’s name suggests, Latter-day Saints believe that they are living in the last days, just before the millennial reign of Jesus – a kingdom where national and political distinctions melt away.

But as with all other churches, its members live in the current day, where political, cultural and social realities shape how they interact with the world around them – and how they vote.

Nicholas Shrum does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.