For decades, letting the world know the plight of Blacks in America fell on the shoulders of journalists like Fletcher Martin.

Martin became the first Black journalist to work with white journalists in the Sun-Times newsroom when he joined the staff as a reporter in 1952 after also being the first Black journalist to be awarded a prestigious Nieman Fellowship.

Martin’s hiring by the Chicago Sun-Times — which throughout its 75 years in business has been a crusader for the underdog and an alternative to its starchy competition — was a big enough deal to be noted in the April 10, 1952, edition of Jet magazine.

Like other young Black Sun-Times reporters who followed, Martin came to the newsroom bearing a burden his white colleagues did not carry.

As famed anti-lynching activist and journalist Ida B. Wells once said: “Somebody must show that the Afro-American is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen on me to do so.”

Within a couple of months, Martin was dispatched to Oklahoma to cover the NAACP’s convention, a yearly event he would cover for years.

“My father was at home with the Sun-Times,” Martin’s son, the Rev. Peter Nieman Martin Sr., said in a newsletter commemorating the Nieman Foundation for Journalism’s 75th anniversary.

Martin covered civil rights and “introduced the city to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.,” the son said of his father, who died in 2005.

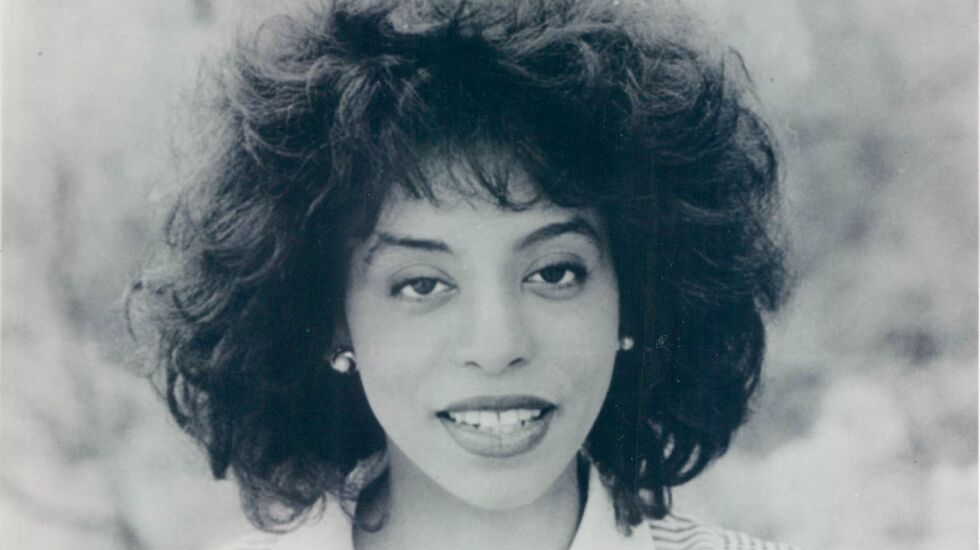

The first Black woman to work in the newsroom was Lillian Calhoun, who joined the Sun-Times in 1965. Before getting hired by the Sun-Times, Calhoun was a reporter for Ebony and Jet magazines and a features editor and columnist for the Chicago Defender, according to a Chicago Tribune obit after she died in 2006.

Another Lillian — Lillian Williams — arrived in 1973.

“When I started at the Sun-Times, there was one other Black person in the newsroom,” she told me. “It was the era when everybody was wearing Afros. When I stepped into the newsroom — let’s just say I got a lot of looks,” said Williams, bursting into laughter.

Williams grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, and earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Northwestern University.

“I was very young compared to the very seasoned Chicago Sun-Times newsroom,” she said. “I was thrilled that I was there.

“What I quickly found out was I was working on two tracks. I was responsible for my journalism reporting assignments like everyone else, and [Black reporters] were advocates for diversifying the newsroom.”

Williams, who also is a former Columbia College Chicago professor, pointed out that in 1970, Black residents made up about 30% of Chicago’s population.

“Our point in meetings with Sun-Times management was there should be a Black person on the editorial board, and we needed more people of color in management,” Williams said. “I think it made a difference. It opened the doors for a Black person to be on the editorial board. I am thankful I had the opportunity to contribute.”

Not every Black journalist’s integration experience was as gratifying.

Lacy J. Banks was the newspaper’s first Black sportswriter, covering the Chicago Bulls. After a sports editor rejected some columns Banks wrote — a move the reporter labeled “racist”— and the Black press got hold of the story, Banks was fired.

It took a ruling by a federal arbitrator for Banks to get his job back. Banks held down his beat from 1972 nearly until his death in 2012 at 68.

In the 1980s, the Sun-Times was a pipeline for Black journalists to bigger markets.

Don Terry, now the Chicago Police Department’s director of news affairs and communications, came aboard the Sun-Times when the Chicago Tribune wanted him to go to the suburbs.

The Sun-Times “sent me to City Hall as the No. 2 person, working with Harry Golden,” Terry said, referring to the paper’s legendary City Hall reporter. “I covered a lot of the ’86-’87 campaign of Mayor Harold Washington. It was an exciting time.

“When I left the Sun-Times to go to The New York Times, [Black reporters] gave me Dempsey Travis’ book ‘Black Politics,’ ” Terry said. “There was always concern over those issues of diversity.

“The Sun-Times was welcoming, nurturing, all of those things. But I felt there was a need to push for diversity, and not just in editing ranks. In those days, the Sun-Times was a good place to be.”

As elusive as diversity can be, it is still a goal worth pursuing.