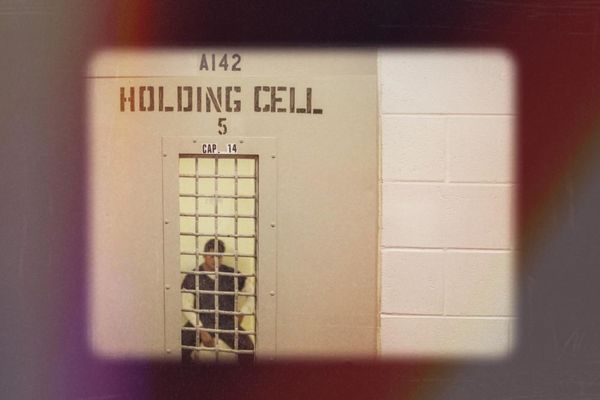

People who are convicted of felonies might think they can’t vote.

Even in California, where they do have the right to vote, people convicted of felonies cite cases in Florida and Texas where people with felonies who have completed their sentences have been arrested and sentenced to prison for trying to vote illegally.

It’s almost an article of faith that a person loses their right to vote once they have been convicted.

But that’s not universally true.

Since 1997, 26 states and Washington have passed reforms that have expanded voting eligibility to over 2 million people with felony convictions.

The reforms reflect the growing recognition by some politicians that felony disenfranchisement laws often excluded people from voting long after they served their sentences. Rooted in historical racism that restricted access to the ballot box, these laws are at odds with the idea that punishment should end after someone completes their sentence.

But with these reforms comes a new challenge – ensuring that people who have the right to vote are aware that they can.

Different states, different laws

A popular assumption among the general public, and even among those convicted of felonies, is that they can’t vote for life.

During our research, we conducted interviews and focus groups with 137 people, as well as text message conversations with over 1,800 people across five states (California, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Texas). Delia, a 40-year-old Hispanic woman in Texas, explained: “It’s very confusing on purpose. The majority of people that I know, who get booked in and are going to jail, one of the biggest things is, you can’t ever vote again. Right. And so, that’s what I believed.”

Laws on felony disenfranchisement vary by state]. In some instances, people with convictions can still vote while they are serving time in Maine, Vermont and Washington, D.C.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, those convicted of felonies have their rights automatically restored in 23 states when released from prison. But in 10 other states, those convicted of certain felonies can lose rights indefinitely or require a governor’s pardon for voting rights to be restored.

Making matters even more confusing is that state laws make different distinctions on who can and cannot vote. In some cases, the distinctions are based on whether the conviction was a felony or misdemeanor.

Other states distinguish between the timing of the end of imprisonment, parole or probation – and whether all fines and fees have been paid.

The Florida eligibility question

In 2018, for example, Florida voters approved a ballot initiative that “restores the voting rights of Floridians with felony convictions after they complete all terms of their sentence including parole or probation.”

Known as Amendment 4, the measure excluded people who committed murder or a felony sex offense.

But before the measure went into effect, a legal dispute arose over the definition of what it meant to complete a sentence. In 2019, Florida’s Republican-controlled Legislature passed a law that required payment of outstanding fees and fines before a person convicted of a felony conviction could regain their voting rights.

Though the American Civil Liberties Union challenged the constitutionality of the law in court, a federal appellate court backed the Republican lawmakers.

As a result, an estimated 730,000 Floridians who have completed their sentences remain disenfranchised.

Extending voting rights

Over the past nearly 30 years, many states have moved to make it easier for those convicted of felonies to regain their voting rights, starting in 1997 in Texas, where lawmakers eliminated a two-year waiting period before a person convicted of a felony regained their right to vote.

As a result, the number of people with felonies who had lost their right to vote dropped from a high of 6.1 million in 2016 to an estimated 4 million in this election, according to the Sentencing Project. During the U.S. presidential election in 2020, that number was 5.2 million.

So far in 2024 alone, officials in three states have tinkered with their laws on voter eligibility requirements for people convicted of felonies.

In Virginia, lawmakers approved on April 5 a new law that allows registered voters who are imprisoned while awaiting trial or have been convicted of a misdemeanor to vote by absentee ballot.

A month later, in May, Oklahoma lawmakers clarified their existing laws by passing a measure that allows people convicted of felonies to vote under certain conditions, such as receiving a pardon or a reduction of their felony conviction to a lesser misdemeanor.

Though passed by state lawmakers in April 2024, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled on Oct. 16 that the new law could take effect. The law eliminates the two-year waiting period following the completion of a prison sentence before voting rights could be restored.

Increasing voter turnout

Numerous studies of those with felony convictions have shown that they believe the voting process is unclear and confusing.

In our study of voting behavior of people with convictions, we interviewed Raymond, a 49-year-old Black man in Michigan. When asked about the process of registering to vote, he told us: “I ain’t going to say scary, but it was unfamiliar. It can be overwhelming for people who don’t want to do it. You don’t know where to go, you don’t know who to really vote for.”

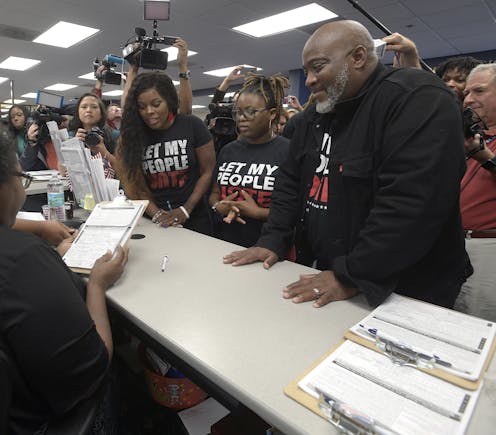

To get the word out to newly eligible voters, community organizations across the U.S. have launched grassroots operations to inform people with convictions of their voting rights and help guide them through the registration process.

As part of that effort, community organizations such as Alliance for Safety and Justice and TimeDone are working with academic researchers to further understand how different methods of outreach can increase voter turnout among people with felony convictions.

With many people newly eligible to vote in their first presidential election this year, I believe providing them with accurate information about voting and their state’s felony voting laws is critical to ensuring that the idea of a second chance includes the right to vote.

Naomi F. Sugie receives funding from the National Science Foundation, National Endowment for the Humanities, Council on Library and Information Resources, Orange County, Alliance for Safety and Justice, Crankstart, and Public Agenda.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.