The future of Southend United Football Club hangs in the balance. A petition by His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) to have the club wound up over unpaid tax liabilities has just been adjourned by the high court until March. The court had previously granted one stay of execution from November to January, but agreed another after being persuaded by lawyers for the fifth-tier club that it may yet clear its debts.

It comes shortly after Scunthorpe United, another club from the same division, received a similar winding-up petition earlier this month. Both clubs are around 120 years old and were in recent times playing football in the Championship, English football’s second tier: Southend in 2007 and Scunthorpe in 2013.

Without a change in fortunes both clubs will go the same way as numerous other clubs that have been liquidated in recent years, such as New Brighton (1983), Aldershot (1992), Bury (2019) and Macclesfield Town (2020).

Behind every collapse is a story of people losing their jobs and investors losing money, but the community uniquely suffers too. It often has to endure a lengthy period of uncertainty, perhaps taking regular abuse from rival supporters. And when the worst comes to the worst, lots of businesses that rely on the club get hit by the fall out.

Supporters of a collapsed club will often start a new outfit with a similar name at the bottom of the football league pyramid and start climbing again – Wimbledon, Aldershot and Accrington Stanley are examples. But by then, so much damage has been done that could have been avoided. So what can be done to keep clubs like these in business?

The long failure list

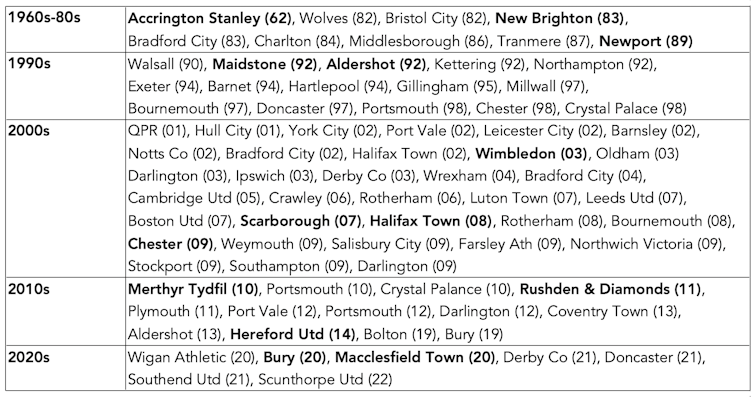

Football insolvency is a continual stalking horse for many clubs outside the Premier League. The table below shows just how many have succumbed to some kind of insolvency procedure over the years, with liquidations marked in bold.

English clubs entering insolvency procedures

Football clubs are different from the average company. They have what can be called an intrinsic viability. Fans will stick with a club through thick and thin, meaning they are very likely to have a reliable revenue stream far into the future.

A football club is a way of life for fans. As well as the current team and fixture list, they take an interest in everything from the club’s history to efforts to bring on youth players to social outreach programmes. For many, the club will be a central nexus point for the area.

Many fans are prepared to dip into their own pockets to facilitate a recovery. For example, when Wigan Athletic was struggling in 2020, supporters responded by raising £500,000. It’s very different to anything most consumers would do for, say, their favourite high-street store.

It therefore makes sense to treat football clubs differently to other businesses when they run into financial trouble. Liquidation is a costly and requires a pointless rebuilding process with a new club that should not be necessary.

How the law works

UK insolvency law has since 1986 basically prioritised rescue procedures over liquidation. This was on the back of a government-initiated investigation into this area by insolvency expert Sir Kenneth Cork. The 1982 Cork report said:

We believe that a concern for the livelihood and wellbeing of those dependent upon an enterprise, which may be the lifeblood of a whole town or even region, is a legitimate factor to which a modern law of insolvency must have regard. The chain reaction consequent upon any given failure can potentially be so disastrous to creditors, employees and the community, that it must not be overlooked.

The 1986 Insolvency Act duly introduced administration and company voluntary arrangements (CVAs) as ways of rescuing a company as a going concern. If this is the policy in general, it should be used wherever possible in a sport that goes to the heart of local communities.

Football League rules do say that clubs in financial difficulty are supposed to go down one of these two routes. With a CVA, the directors stay in control in exchange for reaching a deal with creditors for repaying them. With administration, an administrator temporarily takes over to see whether the business can be rescued and how best to repay creditors. Clubs often emerge from such arrangements and get back to business as usual.

Yet creditors have to essentially agree to let them go ahead. In football, HMRC is often a club’s largest creditor so it’s often their call. When a club’s tax issues are sufficiently bad, they sometimes decide to go straight for a winding-up petition – which appears to be what has happened at Southend United and Scunthorpe.

HMRC always has to be careful in these situations. Without particularly commenting on these two cases, one can imagine that after several years of being relatively inactive during the pandemic, it might be tempted to make an example of some easy targets.

Equally, a club should be able to avoid getting anywhere near a winding-up petition by engaging with the tax authority early enough. For clubs and creditors alike, it’s vital that they remember that there’s a whole community at stake and act accordingly.

Clubs should also be open to alternatives. One might be some financial involvement from the local authority. For example, Wigan Council in north-west England took a stake in Wigan FC after it ran into trouble a couple of years ago. This engagement helps with local community cohesion, particularly with local youngsters and schools.

Another option might be for clubs to become not-for-profit enterprises. AFC Wimbledon is a case in point. The supporters’ group use The Dons Trust to maintain 75% ownership of the club. This is an industrial and provident society which trades for the benefit of the broader community.

Outside the top divisions, such structures might be more appropriate to protect a club for its community. It’s vital to remember that football clubs are a way of life, not just businesses.

John Tribe does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.