You’d probably notice if the car that cut you off or pulled up beside you at a light didn’t have a driver. In the UK, self-driving cars are still required by law to have a safety driver at the wheel, so it is difficult to notice them. But car companies have been testing automated vehicles on UK roads at least since 2017.

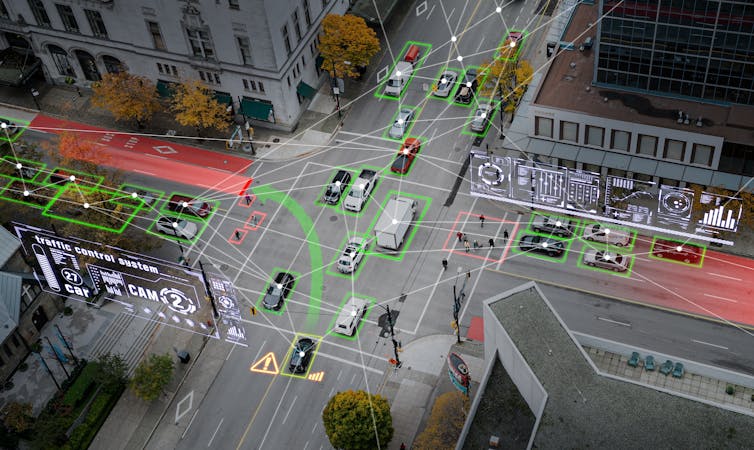

Self-driving cars use Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology to steer themselves and navigate around obstacles. But they aren’t the only use of AI in the streets today. This technology is being introduced in many different ways, for example in cameras that detect whether people are speeding or using mobile phones while driving.

As part of the AI in the street project, my colleagues and I at several UK universities studied how residents and visitors experience the presence of AI in public spaces.

While many of the people we spoke to were interested in what AI is used for in the street, they were more likely to notice the physical presence of the technology – feeling that all this equipment makes for a busy and cluttered environment. Some questioned the extent to which the technology makes things better for them.

Here are five places you might encounter AI in cities in the UK and not realise it.

1. Traffic lights

In cities like Manchester, Coventry and York, some roads have been equipped with a technology called Green Light Optimal Speed Advisory (Glosa) as part of real-world technology trials. This system is designed to nudge cars to reduce their speed when the light is about to turn, meaning that cars no longer need to speed up or stop unexpectedly. Currently this system only works with cars that have the Glosa app installed.

Glosa captures traffic data in real time, which can be used to analyse patterns with AI, and nudge cars and pedestrians to optimise traffic flow. The Manchester trial showed this technology may also be used to reduce car emissions.

2. Lampposts

In UK cities, some lampposts have been equipped with cameras, sensors and communications equipment, some of which are AI-enabled. This kit may include speed detectors, environmental sensors to measure air quality, and number plate or facial recognition.

They may also be equipped with units that transmit data captured by cameras and sensors in the street over the internet. Some of this data is used for fairly basic purposes, such as matching number plates to vehicle registrations on record. Some cities provide access to third parties so they can analyse street data for their own purposes, for example, to discover patterns in road use.

In Coventry, one resident told my colleagues and I: “The cameras in the lampposts, they do not communicate with us, they are above our heads, literally, they communicate with elsewhere […] These boxes are not giving anything, they are just extracting. They seem designed not to draw attention to themselves.”

3. Billboards

A growing number of advertisements have been created with the aid of AI – including Coca-Cola’s new Christmas ad.

Some digital billboards also use AI to adapt ads to the streets where they are displayed. They use cameras to capture data about the weather or about cars driving by, changing the display accordingly. This was done in Piccadilly Circus. Some analyse data from nearby sources in real time, including phones and social media, to understand the attributes and behaviour of people that see them.

Projects like the one in Piccadilly circus showcase how AI can be used to make advertising more sensitive to the local context, but the reality of smart advertising in the street is often more basic.

Speaking about a digital billboard in Edinburgh, a resident told us: “That camera just tells the advertising company in London when the screen goes down. So I often feel that some of the advertising has nothing to do with Edinburgh.”

4. In and under the pavement

Sensors embedded in the asphalt can be used to monitor the condition of the road and inform passing vehicles about hazards like potholes. Some upcoming trials will use sensors to detect conflict or near misses in the road.

During the pandemic, sensors installed in sewage systems were used to measure the prevalence of the virus in different parts of the country. Today, scientists are using AI to analyse sensor data from sewage systems to detect cracks or defects.

Many of these street sensors are still in their trial phase, and it is a matter for debate whether they “count” as AI or not.

Some would argue that because sensors and cameras in the street just capture data (that is then analysed by AI), they are not part of AI itself. However, as people’s behaviour may be nudged by traffic lights or even wrongly identified based on AI analysis in the street, it seems strange to argue that “AI” does not operate here.

5. In the sky

In some areas, like Coventry city centre, there have been trials with delivery drones. And airborne drone taxis are expected to take off in 2026. The delivery drones are currently only used with human oversight, but are designed to operate autonomously.

When the trial started in 2022, some Coventry residents were sceptical. But whether people approve seems to partly depend on what drones are used for. Hospitals in Warwickshire recently used drones to deliver emergency medical supplies.

A local artist who initially protested against the delivery drones being tested right outside the building where she works, told me that she changed her mind once she heard they are also used for humanitarian purposes.

As this technology becomes more commonplace, it will be important to make sure residents are aware of where it exists – and what it is doing. Our research suggests that when people in the street believe that the technology is not working for them, they are more likely to mistrust it.

One participant pointed out that it is difficult to know what exactly the technology installed in the street is used for, or whether it is even functional: “In my street, we have a semi-functional environmental sensor: someone backed into it with their car, so we’re not sure if it still works.”

Noortje Marres received research funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the Leverhulme Trust.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.