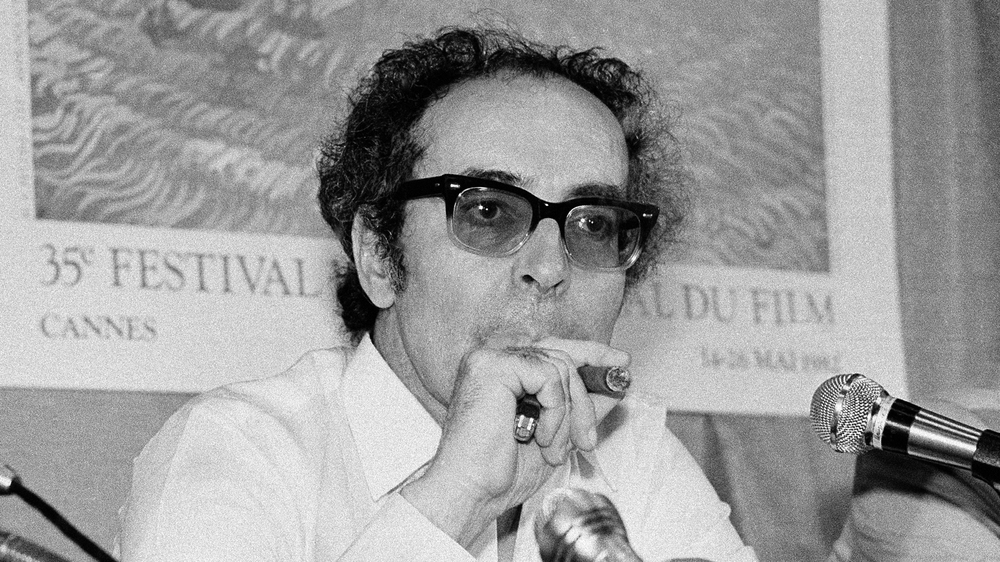

Influential critic and filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, has died peacefully, surrounded by loved ones at his home in the Swiss town of Rolle, on Lake Geneva, his family said in a statement.

The family statement said the 91-year-old Godard had multiple illnesses and died from assisted suicide.

A leader of the French New Wave

The director and onetime "enfant terrible" of the French New Wave helped revolutionize popular cinema in the 1960s, and spent the rest of his career pushing boundaries and reinventing cinematic form.

What greeted audiences in Godard's first feature, the 1960 crime drama Breathless, was the shock of the new.

American actress Jean Seberg was cast opposite a then-unknown Jean Paul Belmondo, cigarette dangling sexily from his lip. He played a penniless young car thief who models himself on Hollywood movie gangsters. After shooting a police officer, he goes on the run to Italy with Seberg, his pregnant girlfriend who seems almost disinterested in him.

They were Tinseltown archetypes, reconceived as the very essence of cool by a director who was a big fan of Hollywood films.

As a critic, Godard had championed directors Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks, and in Breathless, there's a poster of Humphrey Bogart, to underline what Belmondo is going for. But with jump-cut editing, a fractured narrative, and actors interacting with the camera, the filmmaker was establishing himself as part of a New Wave in storytelling — one filled with experimentation and a rejection of accepted technique.

Influence on modern film

"He comes along in 1960," critic David Thompson told NPR's David D'Arcy, "and says in effect, I have seen all the films ever made. I love them, most of them, but I abandon them because they're all out of date. I am going to make a new kind of film, and I'm going to combine the energy and the novelty of ideas of a student, with the story forms of the old films. And for six or seven years, two films a year so we're talking about a fair number of movies, he pulls it off."

In pictures like Contempt, with Brigitte Bardot and Jack Palance, in which he indicts commercial filmmaking; in his science fiction film Alphaville, which places a private eye in a society run by a computer; and most memorably in his scathing, satirical takedown of middle-class materialism, Weekend, a black comedy involving murder, cannibalism and an eight-minute, single-shot traffic-jam-on-a-country-road, that is among the most celebrated film moments of the 1960s.

Weekend premiered just weeks before student and worker protests shut down much of France in May of 1968. Godard, leading a protest that closed the Cannes Film Festival that month, told the crowd that not one of the films in competition represented their causes.

"We are behind the times," said this leader of the French New Wave. And in that moment, his filmmaking took a turn. He embarked on a decade of deliberately revolutionary movies — low-budget provocations, non-commercial, shot in Palestine, Italy, Czechoslovakia, and filled with a Marxist fervor. Tout Va Bien, for instance, starring Yves Montand and Jane Fonda in the story of striking workers at a sausage factory.

Godard's evolution as a creator

This overt emphasis on politics was itself a phase, and by the 1980s, Godard was looking inward and looking at film itself. As his art matured he grew less interested in narrative and more in experimenting, though he'd actually, always been experimenting.

In a public debate in 1966, he kept calling film grammar itself into question, until an exasperated panelist finally sputtered, "Surely you agree that films should have a beginning, a middle part, and an end."

"Yes," conceded Godard, "but not necessarily in that order."

Godard had come to film in his early 20, he told NPR.

"My parents told me about literature, some other people told me about paintings about music, but no one told me about pictures."

So he told others. He began as a critic and, in a sense, he remained one all his life in famously quotable public statements: "All you need to make a movie," he once said "is a girl and a gun."

But as time went on, he was happy to dispense with both girls and guns, and also with plots. A difficult man by nearly all accounts, he feuded with his contemporaries (an argument with his friend and fellow New Wave director Francois Truffaut over the latter's Day for Night in 1973 wasn't resolved before Truffaut's death in 1984). And in his later years, he dismissed notions that contemporary Hollywood could ever make serious films.

If Godard's own work was serious by his lights, in his final decades, it mostly consisted of what might be called visual "essays" — collages of film-and-video clips accompanied by sound and sometimes impenetrable commentary — that found smaller and smaller audiences.

But what he achieved in the early 1960s is still with us, his innovations so absorbed by the mainstream that he has continued to influence filmmakers, some of whom may barely have heard of him, long after the New Wave got old.