A year ago this past Friday, the Federal Reserve raised its key rate to its highest level in 22 years.

That decision — the 11th straight rate increase since early 2022 — was totally expected. Afterward, the larger question of the minds of everyone from home buyers to farmers to Wall Street was whether another rate increase to dampen inflation was coming.

At his news conference after the July 26, 2023 decision, Chairman Jerome Powell said the central bank might boost its key rate again from the new level of 5.25% to 5.5%.

Related: PCE inflation report cements timing of next Fed interest rate cut

But then he suggested the Fed might pass on a rate increase at its next meeting in September.

September came, and, yes, the Fed kept its rate steady. It did the same thing at its Oct. 31-Nov. 1, 2023 meeting.

But things had changed before the meeting. Interest rates were rising again; the 10-year Treasury yield surged to 5%, pushing mortgage rates to 8%. Stocks were slumping.

Suddenly, near the end of October, the 10-year yield peaked and headed lower. Traders had sniffed out a reason: The Fed was starting to get ready to cut rates. Stocks started to rise.

Rates had risen enough

After the Fed's December 17-18 meeting, Powell agreed rates probably wouldn't rise any more. Now he suggested the next rate move would be lower.

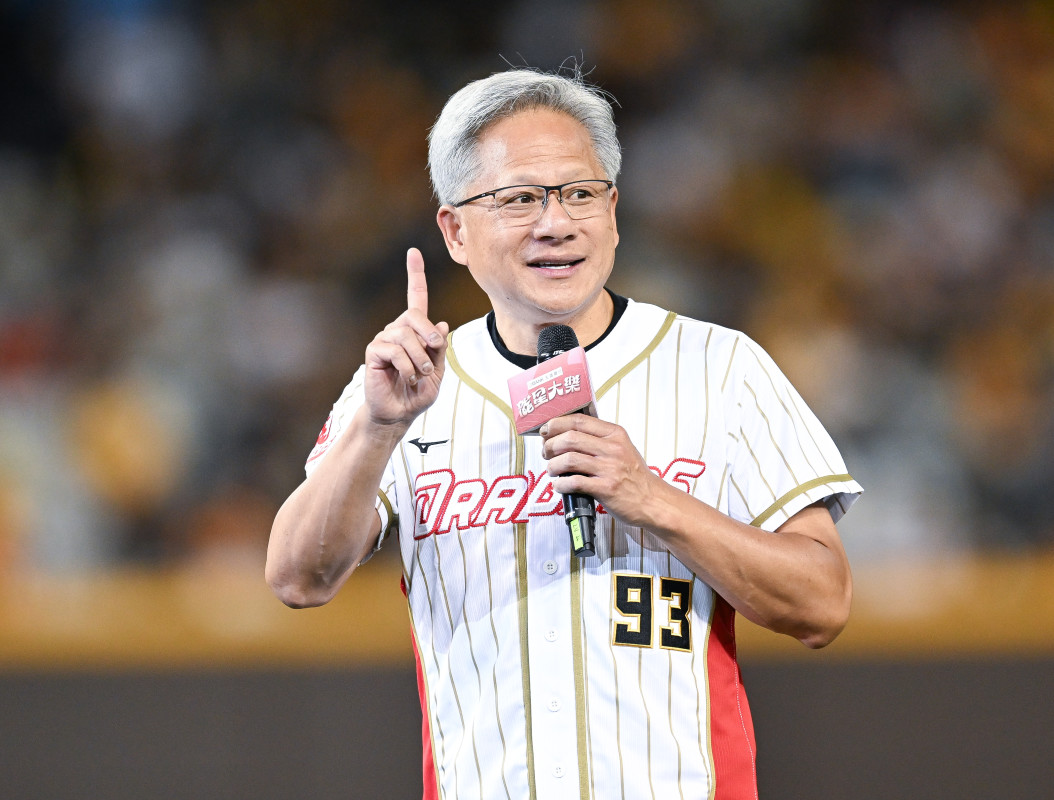

Delirious investors turned a nice rally into something monumental that, among other things, made a household name of Nvidia (NVDA) , the maker of graphics chips that helped artificial intelligence get off the ground.

When 2023 finished, Nvidia shares had soared 230% to $49.52. (The price reflects a 10-for-1 stock split on June 7.) Nvidia is up 128% this year even after a 19.7% correction after June 20.

But Powell didn't say when rates would come down. In fact, inflation continued to be so sticky that a few Fed officials were thinking this spring that rates might have to rise.

That was in the spring.

If the Fed doesn't cut rates this week, it will probably do so in September, and, at his news conference and after the Fed decision, Powell will state a number of reasons for this first rate cut, including:

- Price inflation is closing in on the Fed's goal of 2% a year.

- Bond yields are moving lower. So are mortgage rates, now hovering around 6.8%.

- Housing activity is still weak. New-home sales and existing-home sales in June were weaker than expected.

- The robust jobs market over the last few years is less robust.

He might also mention that business bankruptcies are up substantially from a year ago, with small businesses the most vulnerable.

Reality barges in on the inflation fight

So, why wait any longer?

And it may be that Powell has needed time to get the inflation hawks at the Fed to buy into the decision.

And that drives people close to the Fed, like Bill Dudley, a former Fed vice chairman, a little crazy. He thinks the Fed should cut rates now because Fed dawdling is making a recession unavoidable. His key worry, as he noted in a July 24 column on Bloomberg, is this:

"Deteriorating labor markets generate a self-reinforcing feedback loop. When jobs are harder to find, households trim spending, the economy weakens and businesses reduce investment, which leads to layoffs and further spending cuts."

Dudley is a Fed vet. He had been a promoter of keeping rates high until it was time to cut. The time to cut is now, he wrote.

More Economic Analysis:

- June jobs report bolsters bets on an autumn Fed interest rate cut

- Biden debate flop boosts Trump, but economy may be tougher opponent

- First-half market gains come with a dash of investor unease

So, rate cuts are on everyone's lips now. They will be a huge part of the Fed's agenda during the two-day meeting that starts Tuesday.

If the Fed doesn't cut rates on Wednesday (which is the conventional wisdom), Jerome Powell will certainly say the inflation picture is much improved, with the chances of inflation reignition falling by the day.

And you can circle Sept. 18 as the day the Fed will announce its first rate cut since March 2020, during the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Related: Veteran fund manager sees world of pain coming for stocks