FOR anyone arriving in Newcastle by water, there can be no more of a rambunctious, boisterous, sheer joy-of-life welcome than observing life on Horseshoe Beach.

While the shape of that sliver of sand unfurling along the southern shore near Newcastle harbour's entrance suggests where the beach's name came from, the overwhelming force of community that plays out here has inspired another, more popular, title: The Dog Beach.

Canine chaos rules on the sand, as creatures, two-legged and four-legged, can leave behind the cares of the world and play on the harbour beach.

"It's a special place," says acclaimed artist Michael Bell. "I heard someone say once that we have so many beaches in Newcastle, we've given one to the dogs.

"It's the energy of the place I love, the crazy, anarchic energy.

"And visually, it's incredible, especially when a coal ship passes through, so close to the activity on the beach, with sticks being thrown and dogs running around."

More than being a place where he has taken his canine friends through the years, the Dog Beach, for Michael Bell, has been a muse.

He has created many works featuring the beach, unleashing the harbourside landmark's charm with his paints.

The Dog Beach may be only a couple of hundred metres long, but for the artist it has offered endless subjects, and it has given him a different perspective on harbour life.

"To be at the mouth of the harbour, watching the ships, it's a different relationship with the harbour," he explains.

"Especially after the floods, and all the stuff that's washed up there, and with people building structures and sculptures."

For much of 2022, the beach has been strewn with debris carried down the rain-swollen Hunter River, providing dogs with plenty of sticks, and creative humans with the materials to construct shelters from the driftwood.

But the artist himself has resisted visiting the Dog Beach. He was depicting the beach so often, he decided a few years ago to stop painting it, fearing "it's all I had left".

However, the Dog Beach can be seductive. This week, while minding a dog, Michael Bell has returned to the sand. And the sight of a straggly row of "teepees" constructed from the debris along the beach beguiled him.

"It looked like some medieval village," he says.

It seems as though the sand has not only got under his nails once more but into his soul, as a result of that visit. Which means The Dog Beach could well return to a Michael Bell painting, pouncing and panting its way across the canvas.

"I think I might do one," the artist says, with a spark in his voice. "One with all that driftwood."

OVERLOOKING the Dog Beach is a stern reminder set in stone that the harbour is not just a playground but a strategic asset that has had to be defended.

Fort Scratchley was built on Signal Hill in the 1880s, at a time when there were fears of a Russian attack from across the seas. As a coal port, Newcastle was vital to British shipping.

In time, other defensive measures were installed around, and under, the harbour's waters, including mines, to repel invading vessels.

Yet for decades invaders never came, and the fort's guns were not fired in anger until the height of World War Two. In the early hours of June 8, 1942, a Japanese submarine surfaced in Stockton Bight and fired shells towards the port, with the BHP steelworks and a floating dock believed to be the prime targets.

The fort's guns fired four rounds at the submarine, which slipped into the depths and slunk away. The Japanese shelling caused no deaths and minimal damage, but that furious half-hour created history.

"They were the only land-based guns in Australia ever to be involved in a naval engagement," explains Frank Carter, the president of the Fort Scratchley Historical Society. "It puts us in another unique position in Australia's history."

Eighty years on, each day at 1pm, a cannon is fired at the fort, not out of anger but to mark time. Down the hill to the west, atop the clock tower of the stately former Customs House building, a time ball is lowered also at 1pm. Those two daily actions are not just telling the time, they are recalling times past.

From the 1870s, a time ball was dropped and a cannon fired at 1pm every day, so that mariners in port could set their ship's chronometers, which were vital at sea for determining longitude and therefore helping determine a vessel's position.

The cannon fire ceased after a couple of decades, but the visual time signal continued until the 1940s when technology made the ball drop redundant.

But both the gun fire and the ball drop are back, which can be enjoyed from the elevated position of the fort or by whiling away time at the old Customs House building. What was once a key part of the port's administration is now a hotel.

Signal Hill had a connection with the harbour before Fort Scratchley.

In the early days of European settlement, a coal-fired beacon was lit on the hill, as a warning to mariners.

And prior to the fort's construction, Frank Carter says, the Harbour Master's cottage was on Signal Hill, providing the official with something that attracts visitors to the fort these days - a panoramic view of the port.

"You can see everything, from when a ship passes Nobbys through to when it has berthed, so you can't get much better," Frank Carter says.

DOWN on the waterfront, beside the Port Authority of NSW building where Newcastle's Harbour Master works now, is a historical stone boat harbour.

It was built in 1866, as part of the pilot station, its occupants helping guide ships in and out of the port. The past flows into the present in the little harbour; marine pilots' boats are berthed there, protected by the stone walls.

As he walks around the grounds of his workplace, Harbour Master Vikas Bangia reflects on the history held in the stone walls, in the old boat shed, and, indeed, in the water itself.

After all, a pilot service has been operating in this port since 1812.

And the position Vikas Bangia fulfils, overseeing about 4500 ship movements in and out of the port each year, has been part of harbour life for almost 190 years.

"The first Harbour Master was appointed in 1834," explains Captain Bangia, who has been in the job for about 18 months.

"So it was a very emotional moment for me when I was appointed Harbour Master. The legacy I've inherited, and all the previous Harbour Masters, I want to acknowledge the good work they've done, and I hope I can carry that forward."

This stone structure conjures a slice of Newcastle's past all but forgotten, when crews in wooden craft would cast off from the calm and security of the harbour and head to sea to meet approaching ships, whether to help guide them to port or, as the "butcher boats" did, race out to be the first to snare the food supply contract for a visiting vessel.

Then there were the lifeboat crews, venturing into the foulest weather to help stricken vessels.

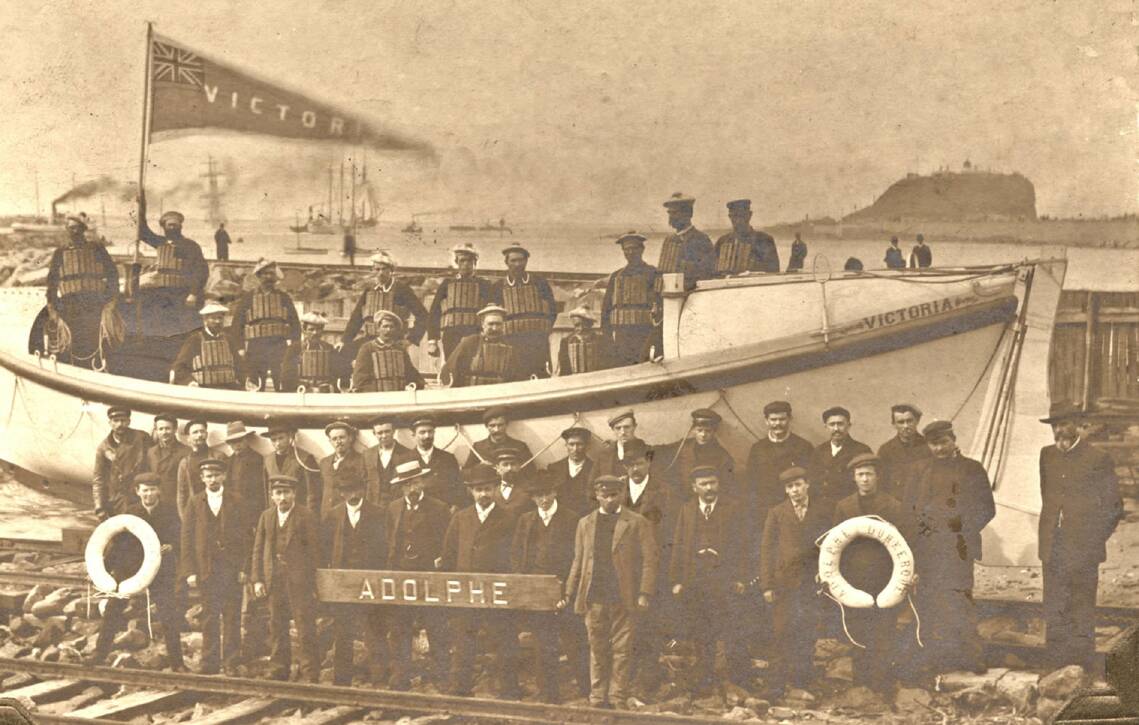

The best-known was the lifeboat Victoria, which was based just near the pilot station, and whose crew was celebrated for saving those on board the French barque, Adolphe, in 1904, when the sailing ship was grounded on the notorious Oyster Bank near the harbour's entrance.

"They were extraordinary," says author Pamela B. Harrison about the lifeboat crews.

The great-granddaughter of Captain Henry Newton, Newcastle's Harbour Master from 1884 to 1906, Pamela Harrison wrote a book with the main title, Man the Lifeboat!, documenting the history of the Newcastle Lifeboat Service and The Rocket Brigade.

The lifeboat service was launched in 1838, but crews were confronting the elements and helping vessels in trouble long before that.

"Some died in the early days, because they couldn't get back after going out," Pamela Harrison says.

According to the author, the first person documented to have died while trying to rescue people from a ship was Thomas Shirley, a convict, in 1808. The vessel, the Halcyon, was saved; Thomas Shirley was drowned.

"The crews that went out to help were convict crews," Pamela Harrison says.

The historic boat harbour is more than a monument to the port's early days. It is also a survivor in the midst of a dramatically changed and reshaped waterfront.

The Joy Cummings Promenade, named in honour of a former lord mayor and a popular path for walkers, joggers and those simply wanting to observe life on the water, and Foreshore Park are mostly on reclaimed land, according to historian and author of A Harbour from a Creek, Rosemary Melville.

"A lot of that, if you look at the early maps, was sandy and swampy," Rosemary Melville says.

She says there was a raised path across the swampy ground from the pilot station towards Newcastle East.

"It was a 'corduroy footpath'. It was slats of wood all joined together, so the pilots could walk up to their houses, because you couldn't walk on the ground."

In Newcastle harbour, the ambitions of humans were constantly thumping against the current of time and the force of nature.

Thousands of years ago, after the last Ice Age, the sea level rose, and the water filled the valley that had been gouged by the river. And so the harbour was formed in that area where the river meets the sea, which would come to be known as the Hunter estuary.

As the river kept flowing towards the sea, it carried thousands of tonnes of sediment. Just as it still does. After the 2007 "Pasha Bulker" storm, for example, there was about an extra metre of silt in the channel.

And in recent months, after a string of floods in the Hunter, the river has been creating extra work for Port of Newcastle's vessel, the David Allan, in dredging the sediment and taking it out to sea, to help ensure ships don't touch the harbour's bottom.

Glen Hayward, Executive Manager of Marine and Operations for Port of Newcastle, says on average, about 250,000 cubic metres of silt and sand are removed annually from the port's main channel, which is about nine kilometres long.

However, in the first three months of 2022, the David Allan's crew was incredibly busy.

"From January to March 2022, dredging operations removed a year's worth of sediment," Glen Hayward says.

When European ships arrived in the port in the early 1800s, they were confronted with not just a precarious harbour entrance but a maze of shoals and bars.

And, as Ron Boyd, Honorary Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Newcastle, points out, what the river constantly deposited in its own mouth ensured those early crews often didn't have a lot of water to navigate through.

"All you need to do is look back at what the harbour was like when the Europeans first came up," he says. "[The channel] was only six metres deep in most of it. The deepest section between Stockton and the pilot station sat at eight metres deep."

"And that was the channel, which was narrow. The rest of the harbour was even shallower than that."

The harbour was the key to the future of Newcastle and the Hunter, as coal, timber, and agricultural products from up the valley and beyond were exported from the growing port. But the growth of the port, and the region's future, was being hampered by the harbour's challenges and shortcomings.

So by the mid-19th century, the force of nature was met by the will and ingenuity of a young engineer, Edward Orpen Moriarty, who was determined to train the river's mouth. Appointed the engineer for Newcastle Harbour Works in 1855, Moriarty devised a plan to deepen the main channel and make it safer for shipping.

"There was so much hope placed on Moriarty, on his plan to improve the harbour, because Newcastle had a bad reputation because of its port, because it was so dangerous," Rosemary Melville explains.

"Alexander Brown, who was a [Hunter] coal baron, was in San Francisco, selling his coal. Prospective buyers would get a sample of his coal, plus a copy of Moriarty's plan to show how the harbour was going to be improved. That tells you how bad it was. And how good they knew it was going to be afterwards."

Moriarty planned to straighten the bumps from the harbour's edges with stone walls, creating 'a fair, gentle curve' aimed at improving the water's flow. He also proposed constructing the long point that would become known as The Dyke, along with The Basin, off Bullock Island (now Carrington), and to build a northern breakwater from Stockton, and to extend the southern breakwater beyond Nobbys.

Moriarty was reshaping not just the harbour but the future of Newcastle.

"I don't think we can overestimate how important he was," says Rosemary Melville. " Because of him, the port just changed enormously.

"I think it took about 60 years to do. But it was a big plan. It was an ambitious plan. But he knew what he was doing."

The growing demand for Hunter coal, along with other products, and the ceaseless pressure imposed by Mother Nature, meant the work to deepen the harbour continued from the 19th century well into the 20th. One of the projects involved blasting the rock under the blanket of sediment on the harbour's bottom to deepen the channel.

And the dredging goes on, day in, day out.

For as Professor Ron Boyd says of the harbour, "It's actively being filled with sediment all the time, so it has to be constantly dredged."

THE harbour may be a cauldron of activity on, and below, the surface, but it has a host of places that invites you to slow down and simply soak in the experience of being in its presence.

The Queens Wharf area is one of those spots. Standing on the wharf itself, you can look at the harbour's edge curling towards Nobbys.

The rock-armoured wall stretching east is far removed from how the shoreline once looked. Jetties poked into the harbour, and the eras of sail and steam bobbed together along the waterfront. Freight vessels and steamers carrying passengers to Sydney and back would berth here.

Even one of the stars among sailing ships, the Cutty Sark, would pull in along here to have her sleek hull filled with wool, before sprinting across the oceans to Britain.

Further back along the promenade, near the old boat harbour, Rosemary Melville had pointed out the remains of bases for steam cranes, which loaded the ships.

"It makes me dream what it used to be like," said the historian, as she gazed at the remains.

"You can imagine the noises and the smells and the sights.

"All the way along here you had ships loading."

A little to the west of Queens Wharf, there used to be a small harbour that was part of the city's markets, so produce from the Hunter Valley farms could be brought down the river, and local watermen - the Uber Eats/taxi drivers of their day - could deliver supplies to ships in port.

That boat harbour lives in name only. It now plays a different role in transportation; it is a car park.

Across Wharf Road from the Boat Harbour Car Park is another place that is ideally placed for you to feast on port life as it scuttles and slides by: Scratchleys on the Wharf.

This restaurant is perched over the water, and its floor-to-ceiling windows fold up, so the atmosphere of the harbour flows into the dining area.

"The water is our greatest asset," says restaurateur Neil Slater.

"I think it's the magic of just how close you are to the shipping, and how much activity there is on the harbour.

"You get bigger harbour cities, but you are a long way from [the activity]; here, you're right in it. It's incredible to watch."

Since establishing Scratchleys here in 1989, Neil Slater has seen a lot of water flow by, and a lot of changes outside the restaurant's windows.

The steelworks that once filled in the distant view have gone, and the seaplane, which was moored out the front of the restaurant and used the harbour as its runway, has slid into history. There are more recreational craft now on the water, which, Neil Slater adds, is a lot cleaner than in the past.

One thing that hasn't changed for the restaurateur is the impact of floods, as the river shoves debris under the restaurant's piers. So Neil Slater has to go underneath the building, "pushing logs away".

After 33 years serving food, wine and water views, Neil Slater is still transfixed by the magic of the harbour and all that it holds.

"It's incredible to watch," he says. "I look at how big the ships are and think, 'How do they float?'. It's an impressive piece of science."

Next week: 'Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan' - Part Three.

Read more: 'Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan' - Part One.

Read and watch: The night the war came to Newcastle