A common lament among those opposed to immigration is that “in many parts of England, you don’t hear English spoken any more”. But it has never been the case that English was the only language spoken on this island.

Old English, the earliest ancestor of the modern English language, was a relative newcomer to Britain. Its speakers, the Anglo-Saxons, came from different regions across what is now northern Germany to an island where many Celtic languages were spoken alongside Latin – a legacy of southern Britain’s time as a Roman colony. The Old English language was initially joined by other Germanic languages including Old Norse and Frisian.

The Norman Conquest brought speakers of the Romance language Norman French to Britain. They had such an impact on the English language that it shifted to a new stage of development known as Middle English.

No written texts in Britain survive from before the arrival of the Romans. But we know from other historical and archaeological sources that the island was inhabited since the Palaeolithic period, and that people had settled here permanently since the end of the last Ice Age, around 9,000 years ago.

By the Iron Age (circa BCE 800), Britain’s inhabitants were speaking a language known as Proto-Celtic or Common Celtic. By 43AD, when southern Britain became a Roman colony under emperor Claudius, the island was populated by speakers of several Celtic languages. These fell into two sub-groups: the Brythonic languages British (ancestor of modern Welsh and Cornish) and the now-extinct Pictish, and the Goidelic Gaelic (ancestor of modern Irish Gaelic and Scottish Gaelic).

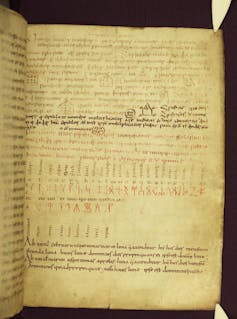

The Romans brought the Latin language and alphabet with them, as well as (eventually) Christianity. All of these had a significant influence on Britain’s history. With the Latin alphabet came written literary culture, which persisted alongside the spoken Latin language after Britain ceased to be a Roman colony.

The close ties between Latin and Christianity can be seen in the Welsh words that were borrowed from Latin, such as llyfr (book, from the Latin liber), ysgol (school, from the Latin schola) and eglwys (church, from the Latin ecclesia).

Impact of Germanic migration

When the Anglo-Saxons came to Britain during the 5th and 6th centuries, it was already a multilingual island in which several Celtic languages and Latin were spoken. The language the Anglo-Saxons spoke after their arrival, Old English, belongs to the Germanic language family, and it too was quickly influenced by Latin as these pagan people converted to Christianity.

As with Welsh, Latin influence can be seen in Old English borrowings such as win (wine, from the Latin vinum), cros (cross, from the Latin crux) and mæsse (mass, from the Latin missa).

From the late 8th century, groups of Scandinavian raiders who spoke a different Germanic language (Old Norse) and have come to be known collectively as Vikings were also a significant presence in Britain. After they transitioned from raiding to settlement, the presence of Old Norse speakers in Britain altered both the grammar and vocabulary of Old English. Many common English words such as kid, stench, egg, yard, skirt, anger, fight, law and knife were originally borrowed from Old Norse.

These were not the only languages present in early medieval Britain. Speakers of the Germanic Frisian language, who came from a region that now includes the coast of the Netherlands and north-western Germany, formed a significant community in pre-Norman Britain. They were widely recognised as merchants, traders and sailors.

Greek, Hebrew and Latin were revered by early medieval Christians as the “three sacred languages”. While there were no Jewish communities in Anglo-Saxon England, a scholarly knowledge of Hebrew did exist. Greek held a prominent place in the religious and intellectual culture of early Anglo-Saxon England, thanks in large part to the efforts of two scholars, Theodore and Hadrian, who founded an important school at Canterbury in the 7th century.

After the Norman Conquest, Britain’s multilingual culture expanded, including Norman French, Middle English, Latin, Welsh, Cornish, Scottish Gaelic, Scots and Flemish. The political consequences of the Norman Conquest meant that Norman French (which would eventually develop into its own dialect, known as Anglo-Norman) became the de facto language of commerce, government and politics. This in turn led to some interesting class implications.

While the Old Norse borrowings noted above have become “homely” words in modern English, their Norman French equivalents have come to signify upper-class versions of the same concept. Consider the resonances of kid/heir, stench/odour, egg/omelette, yard/court, skirt/costume, anger/cruelty, fight/battle, law/parliament or knife/armour.

Britain has always been a place where many languages were not just spoken simultaneously, but interacted with one another. The modern English we speak today was shaped by these interactions.

Lindy Brady does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.