Contrary to Groundswell's assertions, pricing livestock pollution is reasonable, rooted in science and will see global greenhouse emissions fall, Marc Daalder reports

Analysis: Just 1.16 percent of the population are farmers, but they're behind 5.5 percent of gross domestic product, 48 percent of greenhouse gas emissions and more than 70 percent of the global warming New Zealand is currently responsible for.

There are far fewer ways to reduce greenhouse pollution from agriculture than there are for other sectors and New Zealand's farmers are, per kilogram of meat or milk, among the least emissions-intensive in the world, but they also face much more lenient reduction targets.

These are the inconvenient truths underlying the vitriolic debate over pricing farm emissions.

They aren't inherently contradictory, but they set up difficult trade-offs - thornier than in other sectors of the economy. The situation is incredibly complex and nuanced, but that makes it so much easier for cheap, over-simplified slogans to slice through the morass.

We saw this on Thursday when farmers took to city streets to protest the pricing proposal. They said it was unfair, asked too much of the sector and won't actually cut emissions.

Like Earth if heat-trapping gases aren't seriously curtailed, these concerns are overcooked.

Global warming

Two myths in particular have come to dominate the discourse in recent days: That farmers are the only ones being asked to halt their contribution to warming and that the pricing scheme will increase global emissions through carbon leakage.

Both are misleading.

The first is rooted in the unique warming dynamics of methane as opposed to long-lived gases like carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide. This issue was thoughtfully traversed in a recent report from the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Simon Upton.

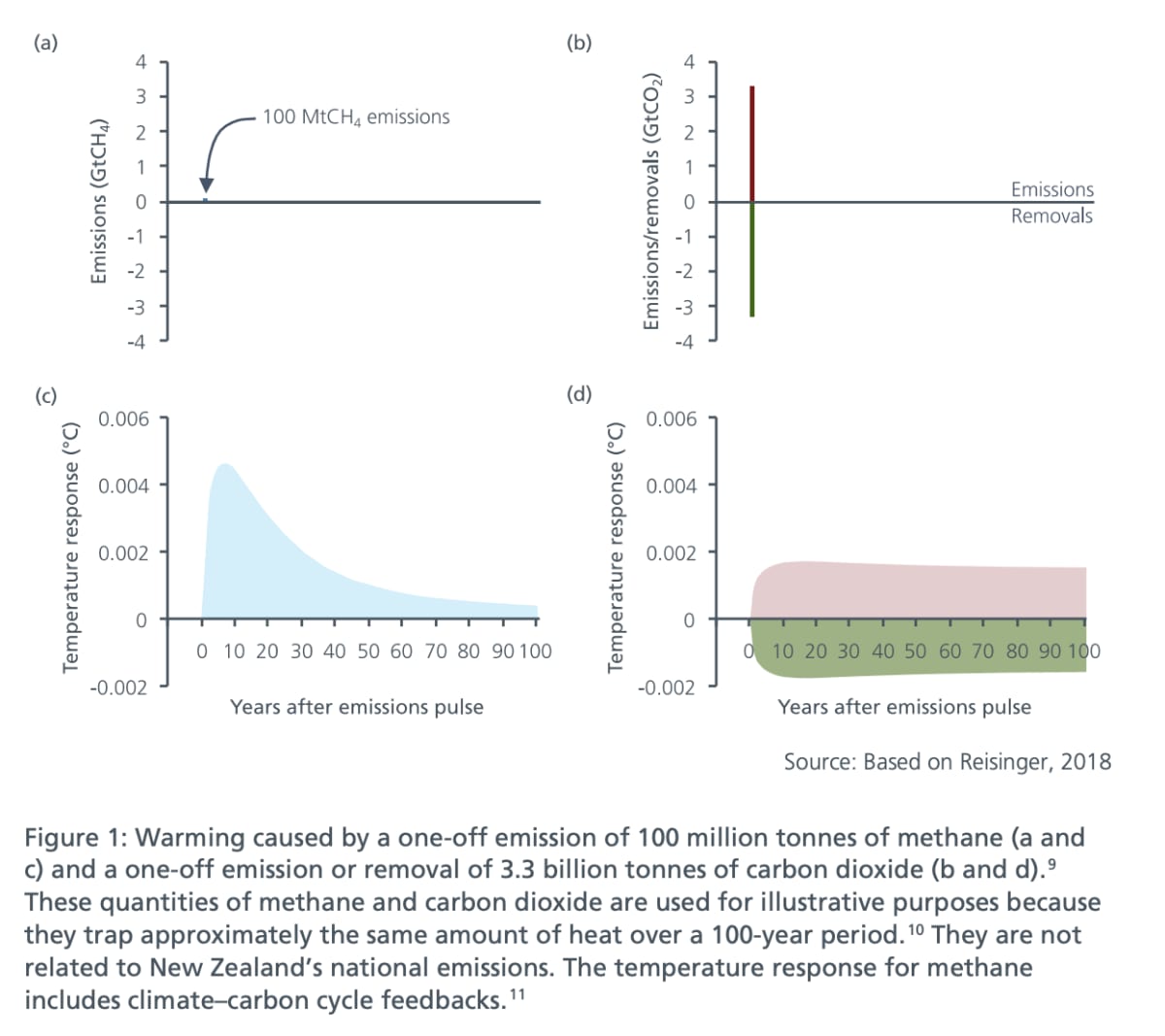

When carbon dioxide enters the atmosphere, it leads to a steep increase in global temperatures within a matter of years. It then remains there, continuing to make the atmosphere warmer than it otherwise would be, for centuries to millennia.

Methane, which in New Zealand arises mostly from livestock digestion processes and a little bit from the decomposition of organic waste, is a different story. When it enters the atmosphere, temperatures skyrocket. A single methane emission 33 times smaller than in our carbon dioxide example would see temperatures peak 2.6 times higher.

Then warming drops sharply as the methane oxidises into water vapour and CO2. After a century, the atmosphere in the carbon dioxide scenario is nearly four times warmer than in the methane one.

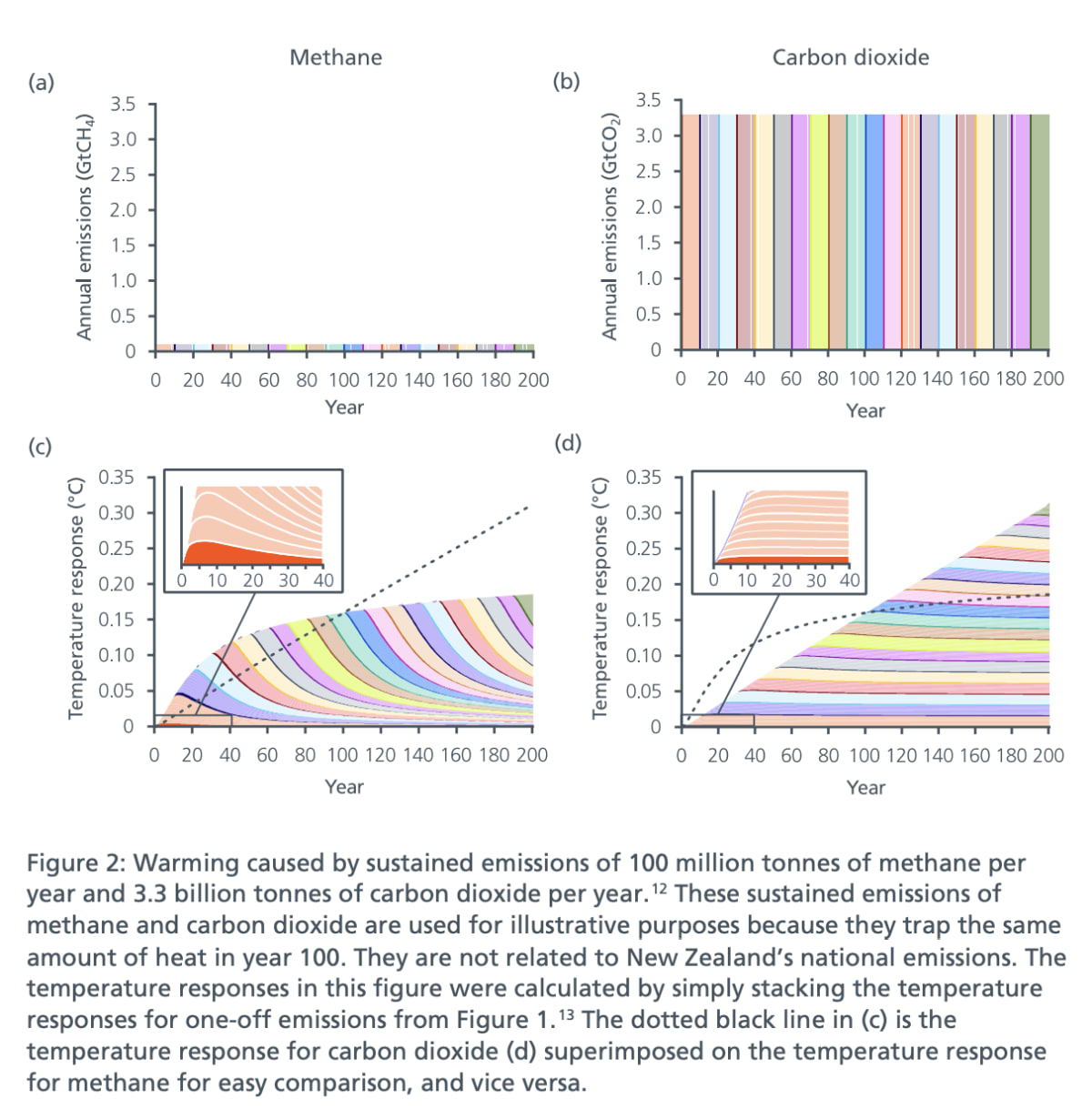

Of course, greenhouse gases aren't usually emitted in single pulses. They are instead sustained, sometimes rising, sometimes falling, sometimes flat, but always there.

For carbon dioxide, each year's emissions have a cumulative, linear warming impact.

For methane, the atmosphere gets warmer each year if emissions are flat, but the rate of heating slows dramatically after the first decade. If emissions are falling slightly (even just 0.3 percent per year), the warming flattens so that the atmosphere is no warmer in year 100 than in year 50.

Compare that to carbon dioxide, where the warming in year 100 from flat emissions would be double that of year 50.

This is what farmers mean when they say the pricing proposal and methane targets (a 10 percent reduction by 2030 and a 24 to 47 percent cut by 2050) are overkill because a much shallower decline could halt any further contribution to warming.

It is true that, if the most ambitious methane and carbon dioxide pathways are followed in New Zealand, warming from methane will be about 1.1 percent below 2020 levels in 2050, compared to a 37 percent increase in warming from CO2.

But this fails to take into account the starting point, in which farming emissions (and particularly methane) are already responsible for a disproportionate amount of warming. It focuses on additional contributions to warming rather than looking at the whole picture: How much warmer the planet is than if no greenhouse pollution had been emitted in the first place.

This is the key metric. The global 1.5C target is in relation to preindustrial levels, not a 1990 starting point when the world was already significantly hotter.

From this perspective, Upton's report shows, warming from New Zealand's livestock methane right now is twice that from our carbon dioxide emissions over the past two centuries. Add in agricultural nitrous oxide and the sector as a whole is behind 2.4 times more warming than carbon dioxide (some of which is attributable to agriculture as well via transport, energy and process heat emissions).

Come 2050, even with the slight decline in methane warming and the jump in carbon heating, agricultural methane and nitrous oxide will still be responsible for 71 percent more warming.

True fairness should take this into account. Farmers have an outsized impact on economic output in New Zealand - but they have a far more outsized impact on global warming than the rest of the economy.

Methane doesn't need to fall to net zero, but more stringent cuts than those required to merely flatten the sector's additional contribution to warming are justified. That's why the gas has a different target than carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, which really do have to hit zero. This recognises the difficulty in reducing methane emissions and the differing warming impacts of the gas, while still acknowledging its disproportionate role in our warming profile.

Emissions leakage

Of course, if methane emissions were to fall in New Zealand but rise overseas, that might look good from carbon accounting perspective but won't do anything for the atmosphere. This is the second concern held by farmers.

If the pricing scheme leads to less milk and meat being exported, then overseas producers will increase supply to compensate. If those farmers produce the same amount of milk and meat at higher emissions, then the amount of methane entering the atmosphere could rise rather than fall, even if our own national methane emissions decline.

This is called emissions leakage and it's a major concern for just about any climate policy. In the Emissions Trading Scheme, which doesn't cover agriculture, trade-exposed emitters get free allocations of carbon units to compensate for the fact that many of their competitors don't face a carbon price. This helps avoid a scenario where the aluminium or steel smelter shuts up shop and global demand is instead met by dirtier metals produced in China.

Farmers are already set to enjoy this allocation. The levy rate for nitrous oxide will be set in relation to the Emissions Trading Scheme price but with a 95 percent discount. The levy rate for methane isn't technically discounted in this manner, but the example rates offered by the Government and He Waka Eke Noa were arrived at by discounting 95 percent from potential future carbon prices.

Despite this, modelling conducted by both the Government and He Waka Eke Noa shows both iterations of the pricing scheme - including the one backed by the primary sector - would likely lead to production declines.

In all cases, greenhouse gas emissions would fall by a greater percentage than milk, meat and wool production. This is because there are already mitigations open to farmers to reduce emissions without cutting production, like better farm management practices and a limited set of methane-busting technology.

What about that remaining lost production? The evidence is unclear on whether this would lead to a rise in global emissions. At least four quantitative analyses have been conducted on the potential for agricultural emissions leakage from New Zealand, but all are highly uncertain because this is the first time agricultural emissions have ever been priced.

The first of these, an OECD report from last year, suggested every tonne of agricultural emissions reduced in New Zealand would be replaced by 550 kilograms overseas. Global emissions still fall, but by a more limited amount.

Modelling by the Government was more conservative, estimating that 65 percent of emissions reductions here would leak overseas. The Climate Change Commission also concluded global emissions would still fall but not by as much as New Zealand's emissions in its own report.

The fourth analysis, commissioned by He Waka Eke Noa, offered a different estimate. The partnership found global emissions would rise by between 7 and 60 percent if agricultural production fell in New Zealand.

This was based on estimates showing dairy, beef and lamb is produced in New Zealand with lower emissions than in the countries where replacement product would be sourced from. These figures may well be true, but the overall conclusions fail to account for a key part of the levy scheme endorsed by both He Waka Eke Noa and the Government.

Early attempts to price agricultural emissions were aimed at a simple processor-level system, in which the few dozen companies which process agricultural products would be charged a levy based on average emissions from agriculture and would pass that cost on to farmers.

He Waka Eke Noa went in a different direction, choosing instead to recommend a levy on emissions at the farm level. This meant each farm was charged based on its actual climate performance. Those with lower emissions face a lower bill, while the more emissions intensive farms pay more.

For this exact reason, we shouldn't assume the reduced production in New Zealand will have our average emissions intensity. The dirtiest production, which emits more greenhouse gases for lower returns, is most likely to be displaced. The overseas production that replaces it may be dirtier or greener or about average for that country - but will still very likely be less emissions intensive than what it is replacing.

While New Zealand on average produces milk and meat with relatively low emissions, other developing countries aren't actually that far above us. If the most emissions intensive production in New Zealand is replaced by average American milk or Australian beef, global emissions will still fall.

Moreover, most of our agricultural competitors (particularly on dairy) have included the sector in their net zero emissions targets. This means that any increase in agricultural emissions in Europe, for example, will have to be met with a decrease in emissions in another sector.

New Zealand is the first country to price agricultural emissions but as the rest of the world wrangles carbon dioxide under control, it won't be the last. As more pricing schemes come into place, the risk of leakage will only further diminish.

There will always be excuses to avoid action. But the longer we wait, the harder the fall when emissions invariably start to come down. It's not sustainable to do nothing about 70 percent of New Zealand's warming - not for trade, not for our international standing and not for the planet.