Winter is an important season for South African agriculture, with some of its key field crops being produced during the cold months of June, July and August, and maturing after that, with harvesting in December. Preparation of the land for winter crops begins in April, which is also the same time harvesting of the summer crops begins.

Farmers in the Western and Northern Cape, Free State, Limpopo and other winter crop growing regions are making arrangements for growing winter wheat, canola, barley and oats.

All of the country’s wheat production takes place during the winter months, making the winter season an important contributor to the country’s wheat needs. South Africa produces roughly 60% of its wheat requirements and imports the balance. It also produces, on average, about 90% of its barley annual consumption. Domestic production of oats is about 64% of annual consumption. The country is self sufficient in canola production. Barley, oats and canola are all winter crops.

This year, the outlook for winter crops is clouded by a difficult operating environment, especially the areas that are under irrigation.

The two biggest headwinds are power cuts and dollar strength. Nevertheless, there are also positives which should take the pressure off food price rises that have hit consumers hard. These positives include a fall in the cost of inputs, like fertiliser and agrochemicals, as well as good harvests from the summer season just ending.

Headwinds

The main contributing factor is the increase in recurring power cuts which will affect irrigation. South Africa’s agriculture has never faced a period of power cuts as severe as the current ones.

The agricultural sector in general is heavily reliant on sustainable energy. For example, recent work by the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP) shows that roughly a third of South Africa’s farming income is directly dependent on irrigation. This shows that disruptions in power supply generally puts at risk a substantive share of the South African agricultural fortunes.

Of all South Africa’s field crops, wheat has the largest production – about half – under irrigation. Of the other key field crops, about 15% of soybeans, 20% of maize and 34% of sugar production are under irrigation.

The potential disruption of irrigation would lead to poor yields, and ultimately a poor harvest. Such an eventuality would lead to an increase in wheat imports.

Industry role-players and the government are alert to the problem and are monitoring the impact closely through a ministerial task team. In addition, Eskom, the power monopoly, along with the government, are exploring possibilities of reducing power cuts which are expected to spike during the winter when demand usually rises.

The second headwind is that South African farmers have not benefited fully from the decline over the past year in the US dollar prices of some of their key inputs such as agrochemicals. This is because of the weakening of the South African rand against the dollar, shaving off some of the benefits of the price decline in US dollar terms.

Thirdly, farmers are experiencing lower commodity prices compared with last year. But a drop in input prices is providing a necessary financial cushion.

There are positives

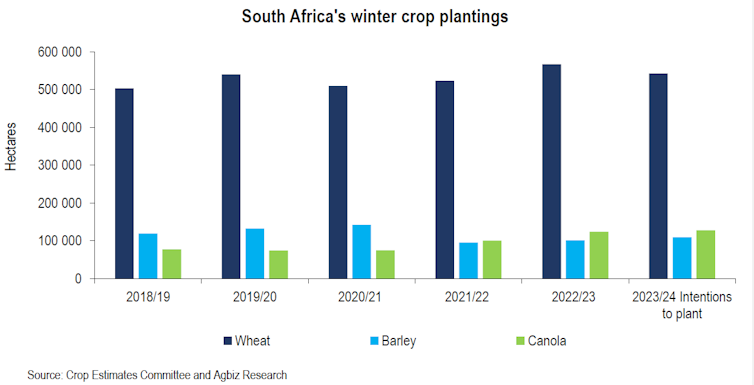

On the plus side, the area plantings for all South Africa’s major crops are expected to be above the five-year average area. This is according to Crop Estimates Committee, a government and industry body that monitors crop production.

Secondly, input prices have come off from last year’s highs. For example, in February 2023, essential agrochemicals such as glyphosate, acetochlor, and atrazine were down in rand terms by 32%, 18%, and 2%, respectively compared to February 2022. These price declines have continued through to March 2023.

These declines would have been higher had the South African Rand not weakened against the US dollar over the same period. That’s because in US dollar terms, the prices of the very same agrochemicals are down by 30% from February 2022. Prices of insecticides and fungicides have also declined notably from last year’s levels.

Also worth noting is that in February 2023, essential fertilisers such as ammonia, urea, di-ammonium phosphate and potassium chloride were down 6%, 36%, 28% and 14% in rand terms, respectively. Again, in US dollar terms, the price decline was more notable, which speaks to the impact of the relatively weaker South African rand on imported products.

These price changes in inputs are vital as they impact vast components of the grain input costs. For example, fertiliser accounts for a third of grain farmers’ input costs, while other agrochemicals account for roughly 13%.

A third positive factor is that the weather conditions for the winter crops also remain positive. In its Seasonal Climate Watch update published on 03 April 2023, the South African Weather Service noted that the winter crop growing regions of South Africa will receive rains.

A fourth positive factor is that the summer crops, which are nearing the harvest process, are in reasonably good condition. I generally expect an ample harvest in most summer crops, which is aligned with the view of the Crop Estimates Committee.

Takeways

From a consumer perspective, developments are broadly positive and bode well for some moderation in consumer food price inflation in the second half of the year, when the decline in commodity prices could begin to filter into the retail prices.

The one major risk is electricity stability. This is as much a risk for farmers as it is for consumers.

However, I am hopeful that the government’s interventions, such as the load curtailment and diesel rebate, to limit the damage of the electricity crisis to food production will help.

If the government’s proposed interventions help during irrigation periods – afternoons and evenings – South Africans can expect a favourable winter season. The reduction in power cuts will also be particularly beneficial for food processors.

Wandile Sihlobo is the Chief Economist of the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa (Agbiz) and a member of the Presidential Economic Advisory Council (PEAC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.