The death of Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa (Arequipa, 1936 - Lima, 2025) marks the end of a Golden Age of Latin American literature. Just as there will not be another generation in Spain like that of Cervantes, Lope de Vega, Calderón de la Barca, Tirso de Molina, Góngora and Quevedo, in America there will not be another like that of Vargas Llosa, Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, César Vallejo, Pablo Neruda, Jorge Luis Borges, Alejo Carpentier and Carlos Fuentes.

Vargas Llosa’s unparalleled awareness of his craft made him perhaps the most accomplished writer among his contemporaries. His discipline to writing, and to doing so impeccably, was absolute.

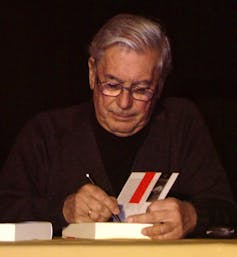

I interviewed him several times, and visited almost all of his libraries, where he worked, in London, Madrid, New York and Peru. The physical order of his working environments was comparable only to the mental order with which he wrote, which was rooted in an obsessively correct use of time.

He never received visitors in the mornings, and in the afternoons he rarely attended to guests before 6 or 7 o'clock. He was convinced that genius is not natural, but the fruit of effort and tenacity, as he wrote in his Letters to a Young Novelist.

Crafting the perfect novel

This ascetic and forceful ethos was etched into his work. His Nobel-winning novels are artefacts, clockwork mechanisms conceived and crafted to the millimetre. Not a single word is misplaced, nor a single loose end left hanging. They have the feeling, at times, of a taut short story sustained over 400 pages.

He once told me that, before writing, he would unfurl a massive amount of paper, a poster the size of a bed sheet. There, he would write down the names of characters, trace ascending or descending lines from each of them, noting when they met, parted, came into conflict, loved, hated, died, and note down the essential events in their journeys. Only with this task completed did he begin to write.

And before any of this, he would inform himself about each and every detail and context for the plot. Whether in his historical novels or purely fictional works, he always meticulously researched times and places, as well as their geographical, meteorological and historical conditions. He travelled with suitcases full of books, which were far bulkier than those dedicated to clothes or personal belongings.

The depths of humanity

If his work ethic was admirable, so too was his intellect, which was marked by a shrewd ability to explore the highs, lows and hidden corners of human capability and experience.

Many of his novels can be summed up by the words of Peruvian writer and critic Julio Ortega, who called them “una arqueología del mal”, an “archaeology of evil”. His sensitivity and ability to scrutinise hearts and minds was indisputable, and he was acutely aware that goodness and virtuous monotony did not make for interesting novels – confrontation was essential.

He focused instead on personal and collective baseness. As well as attracting readers, this also provided a source of incessant and fundamental criticism, one that would carve out his role as spectator, witness and judge of contemporary societies.

He relentlessly targeted abuses of power, dictators, lies, revenge, hatred and attacks on individual freedoms, while also indulging many human shortcomings and deviations, almost always those rooted in mistakes or amorous disappointments. At the same time, he claimed pleasure and life as a game, as a way of overcoming or moving along life’s torturous paths.

A free mind

Mario Vargas Llosa always said what he thought, with little heed for what his millions of readers might think. He did so in his opinion articles, in his conferences, talks, interviews and private conversations. He was always polite, but had no fear of antagonising his audience.

In the same way, his novels took a universal approach to a broad range of themes. This made him one of Spanish literature’s most versatile writers, unlike many others who perpetually write different versions of the same novel, or place themselves at the centre of their own stories. Quality, diversity, perfection, originality and technical experimentation defined his literary output. As a friend of mine quipped to me recently, “all that was left for him to do was write Don Quixote”.

Five of his novels should be counted among the ten or twelve best in the Spanish language: La ciudad y los perros (The Time of the Hero, 1963), La casa verde (The Green House, 1966), Conversación en La Catedral (Conversation in the Cathedral, 1969), La guerra del fin del mundo (The War of the End of the World, 1981) and La fiesta del Chivo (The Feast of the Goat, 2000).

Most of his essays are also true works of art in the field of literary criticism, both in their content and style. His way of explaining profound concepts with accessible language and overwhelmingly strong logic made him one of the contemporary world’s greatest orators and essayists.

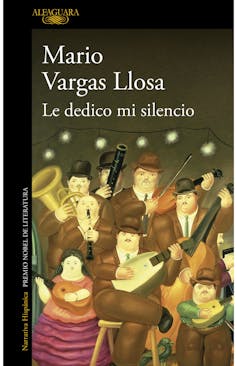

Although he dedicated silence to us in the title of his last novel several years ago, many of us now feel orphaned. Orphaned not only by the loss of someone who taught us to read and write, who revealed hidden worlds and encouraged us to devote ourselves to literature, but also by the knowledge that his death marks the end of an era that will never return. We can find solace, however, in the conviction that 20 centuries from now, people will speak of him as we speak of Virgil today.

Ángel Esteban del Campo no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.