Australian novelist David Ireland, winner of three Miles Franklin awards in the 1970s, and recipient of the Order of Australia in 1981, has died at the age of 94.

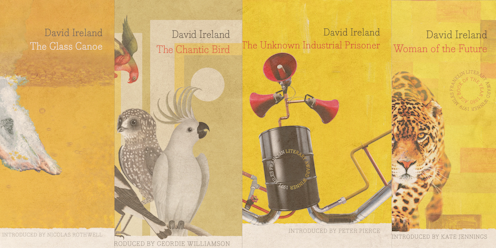

Born in 1927 in Lakemba, New South Wales, he wrote poetry and plays before his first novel, The Chantic Bird, appeared in 1968, the dust-flap proclaiming that Ireland “intends concentrating future efforts on the novel”. It was a good decision, for he won his first Miles Franklin Award four years later and commenced writing full-time the following year.

Read more: The case for David Ireland's The Glass Canoe

Haunted by the plight of the underclass

Fascinated by sweeping existential issues and their impact on the lives of those oblivious to them, Ireland was also compassionately haunted by the plight of society’s underclasses and the great silence about them. Characters in his early novels are factory workers, the unemployed, the homeless, and those lost to alcohol or beset by mental illness.

The Chantic Bird opens with its teenage-delinquent narrator saying, “I’m only telling you this to let you know what a silly thing it is to live like I do” and ends with, “Don’t forget I’m writing to show you what a silly thing it is to live”. For readers, contrarily, the book has demonstrated the potential joy of living, shown why the narrator lives as he does, and exposed wider existential issues.

These themes are fully matured and pressed deeper, harder in his second novel, The Unknown Industrial Prisoner (1971). It won the 1972 Miles Franklin and is widely (if not unanimously) regarded as his best novel. It would be my personal choice as one of the great Australian novels.

Ireland once worked for an oil company and drew upon this for The Unknown Industrial Prisoner, creating Puroil, a coastal Sydney oil refinery out near the mangroves. The lives of the employees, “human bacteria” known only by nicknames, unfold as a mosaic of repetitive work, time-killing blokeyness, and a deep existential yearning: “Somewhere beyond the refinery’s dome of dust and gas the sun shone splendidly golden.”

Poetic futility and conservative furores

The Glass Canoe (1976) uncovers a quirky microcosm, in the tribe of regulars at a Sydney pub. The repellent futility of their drunkenness, violence and sexism becomes bleakly poetic in Ireland’s hands, again teasing out that inarticulate existential yearning, a belief that somehow things are meant to be better than this. The Glass Canoe earned Ireland his second Miles Franklin.

Then came brushes with reactionary conservative authority. In 1978, Film Australia offered funding for a movie based on The Unknown Industrial Prisoner. But then-Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser’s Home Affairs Minister, Bob Ellicott, intervened to cancel the project, on the grounds it was “uncommercial”, in a rare example of political interference in the film industry. Proposals to set The Glass Canoe as a NSW high-school text caused a furore in 1982. The book was labelled “unsuitable” and one scene “pornographic”. Doug Swan, then-Director-General of Education in NSW, confirmed there had been several complaints.

A keynote of Ireland’s style was his use of short sub-headed chapters (29 are nestled in the 35 pages of chapter four of The Unknown Industrial Prisoner). These shatter narrative expectations of chronology or linearity, giving an exhilarating sense of scope, diversity, pluralism. They shout that society teems with individualities – and this is an outright challenge to the worlds the novel focuses on, which are typically as narrow, mono, and blokey as an oil refinery or a pub.

As a young Sydney Uni postgrad in 1976, I met Ireland in his tiny Sydney writing pad and inadvertently opened a door to an empty low-lit room. The floor was carpeted with card-sized slips of paper, some of which fluttered up and relocated upon my entry.

“Sorry, not that door,” said Ireland, and proceeded to explain that his novels evolved from scenes and images, each jotted onto a card. (The Unknown Industrial Prisoner is composed of 330 of these.) He would arrange and rearrange them on the floor, mosaic-style, in a process that was allowed to take however long was needed.

Read more: The literary life of Frank Moorhouse, a giant of Australian letters

Vision, compassion and wit

For A Woman of the Future (1979), he adopted the voice of young Sydneysider Alethea Hunt, placing her in a world of characters undergoing metamorphosis. (At novel’s end, Alethea famously transforms into a leopard.) This won a third Miles Franklin and is now perhaps his best-known novel.

In a review at the time of publication, Rosemary Creswell negotiated the issue of appropriation by suggesting we could perhaps “take heart in the fact that a male writer is attempting so directly to come to terms with the female experience”. She concluded that the novel should be “admired for its acute perceptions, not of political and social constructs for which Ireland is so often praised, but of the nature of the existential condition.” Yes!

By the late 1990s, as Peter Craven once observed, Ireland’s vision “may well have been displaced in the public consciousness by the novels of Peter Carey and Tim Winton, both of them big canvas men”. While Ireland had not abandoned “big canvas”, he became more interested in exploring the nature of creativity itself, and Bloodfather (1987) and The Chosen (1997) both followed the artistic development of young Davis Blood – creating a sense of narrowed focus.

Both books were more “difficult” reads. Narrower focus did not prevent The Chosen from tackling the lives of the 52 characters living in Little River, but it was hard-slog remembering who was who. Ireland’s vision, compassion and wit remained intact – it was just a tad less accessible.

The “preface” to The Unknown Industrial Prisoner – placed just six pages before the end of the book – describes the novel as “this mosaic of one kind of human life, this galaxy of painted slides, my bleak ratio of illuminations”.

Ireland’s legacy is far from a bleak ratio, and extends beyond just one kind of human life; he left us an intricate mosaic of Australian existence in his time.

Van Ikin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.