Fara, in cycling brand terms, is a relative newcomer. Founded in 2015, it is relatively unique in that it is a Scandinavian brand. The cycling industry tends to be focussed on a few nodes - the USA, Taiwan, Italy, Germany - so it’s certainly novel to see a brand come out of Norway, and not even Oslo either. Fara is based in the ‘mid north’, in a town about 30km from Trondheim, roughly the same latitude as Iceland where the national landmass starts to get skinny.

Given the brand’s slightly remote origins, it’s not a surprise that it started with gravel bikes, before moving through all-road until we get the F/Road, a fully-fledged road bike. In the same way Italian bikes have some Italian characteristics in their design and aesthetics, and even ride quality, there is some of that here, though the flavour is Norge.

I’ve had the F/Road for a while now, blasting round my local test loops, so it’s time to see how it stacks up against the best road bikes on the market.

Design and aesthetics

I have a real soft spot for the Norwegians. I used to work there, and the best way I can sum up the national ethos is that the main hardware shop is called ‘Tools’. No messing around, no superfluous flourishes. This is the impression you get with the F/Road.

Fara operates on a direct-to-consumer model and has a pretty comprehensive bike configurer, but my model was relatively stock. A Sram Rival groupset decks out the frame, with the only upgrade being a swap from a traditional two-piece cockpit to a Fara-branded all-in-one unit.

Aesthetically I think it’s a truly beautiful bike. The advantage of being a new brand is you have a pretty clean slate to work from, without decades of design language from which you have to evolve. Here we just have a selection of block colours, a big FARA wordmark, and two thin lines, one on the fork and one on the seat tube. Neat, effective, enough to show some thought has gone in but nothing over the top. Like it or not, cycling is now an extremely aesthetically driven pastime, and the F/Road, especially in this off-white (‘Forest Fog’) colourway, will go with all the fancy kit you can think of (I’m looking at you, MAAP and PNS).

Crucially, the paint is also glossy. Matte bikes look cool but they are a pain to live with and hold onto everything from mud to fingerprints with gusto. Gloss is wipe clean; much better.

Before I dive into the geometry, a few design things are worth mentioning. The F/Road (and the brand’s other bikes) use an expanding bung and headset combination that compresses the headset bearings at the same time as it expands. It’s a one-bolt solution, but I found it a bit fiddly compared to the normal way, which works perfectly well, and this feels a little incongruous against the backdrop of a ‘no nonsense’ brand ethos.

Both the headset and bottom bracket bearings are CeramicSpeed units, which is to be applauded as it’ll give you more time between costly/fiddly headset services primarily. The seatpost is novel in that it is reversible. It has a slight setback, but if you want to slam your saddle forward you can flip it around. It might look a bit odd, but it’ll be far better for your saddle rails.

The frame itself has been ‘aero optimised’ according to Fara, though no specific claims have been made as to wattages. To be honest, given the rest of the marketing is around it just being an enjoyable ride rather than fast, I’m willing to let that slide. It looks relatively aero, and it is UCI legal, but that’s not really its purpose.

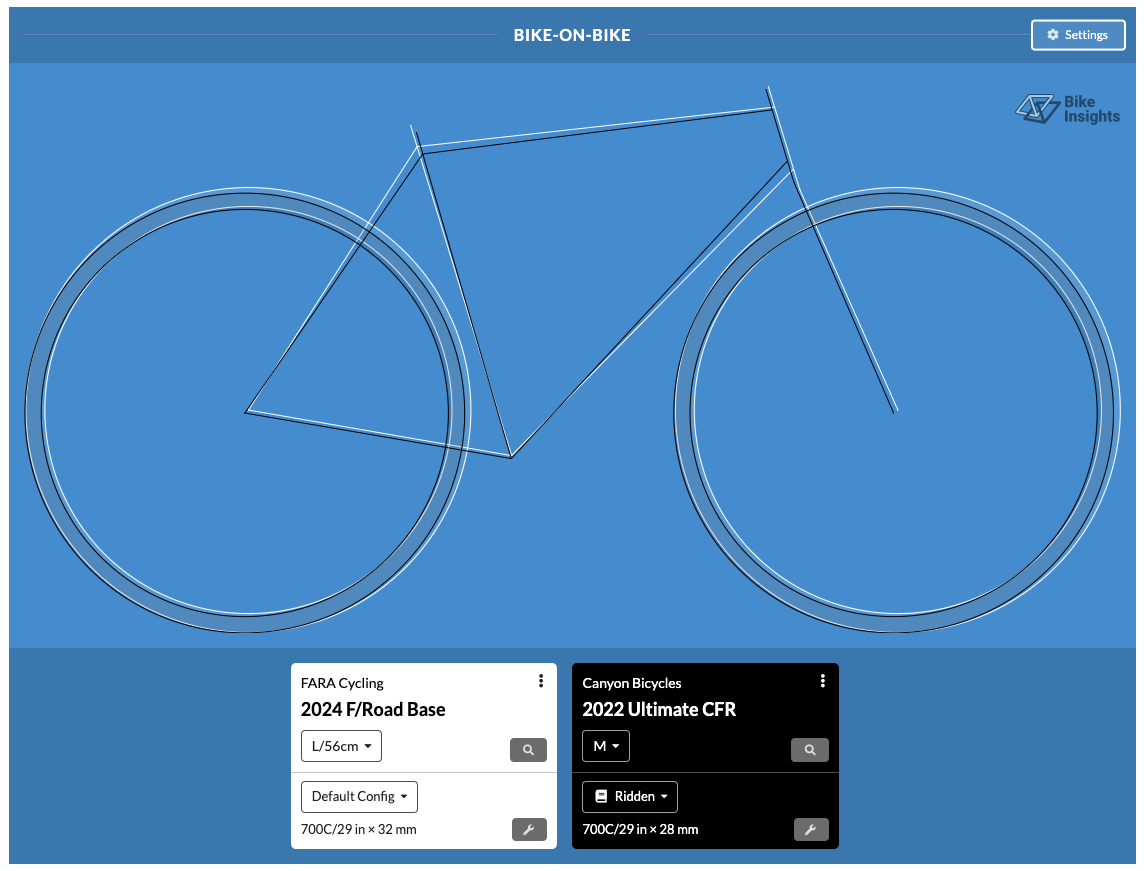

For the geometry nerds out there it’s most similar to the Canyon Ultimate, a bike we found to have very balanced handling. Very similar, in fact, with the main difference being a 0.3-degree slacker head angle and a 0.8-degree slacker seat tube. The Ultimate is slightly lower, and a bit shorter, but with slightly longer chainstays. This plays out in the performance.

Performance

The F/Road is a very pleasant place to be. To kick off with the handling, it shares many similarities with the Ultimate, but in a slightly more mellow package. The Ultimate was nippy but often felt a little skittish, whereas the F/Road felt nimble but relaxed. It’s a far cry from the handling of something like the Colnago C68, which is far longer and slacker and is a little too relaxed for my tastes. It hits a good middle ground where you could quite happily smash a chain gang on it or a mega day out solo in the country where overly rapid handling can become tiresome.

A good handling frameset is nothing without a decent set of wheels and tyres though. The Pirelli P-Zero Race tyres that come fitted aren’t my favourites and didn’t make it into my guide to the best road bike tyres. Much a rubbery sommelier I think the perfect pairing for this bike would be a set of Continental GP5000 AS, in a 30c width. The frame can handle 32mm, and the extra volume would add comfort without much of a sacrifice anywhere, and I think this would really play to its ‘big day out’ strengths.

The wheels are perfectly fine, but feel a little outdated. The internal width of the Fulcrum Racing 4 DB is 19mm, and the Fulcrum website states that this means you can ‘easily fit 25mm tyres’. With 28c being the norm now, and increasing with each year, this is somewhere that may hold the bike back.

The groupset played its part well. I don’t think Sram Rival is a match for 105 Di2, but it is certainly a cheaper way to get electronic shifting. It’s reliable, intuitive, and easy to live with.

Where I most felt the F/Road was at home was on backroads. More than most bikes with this aesthetic I found myself wanting to dive down sideroads and occasional gravel tracks. The fact that no aero claims are made does free you somewhat from feeling like you also have to be aero. While it was fast enough to take the odd PR, I never felt speed was the be-all and end-all of its existence.

I never felt guilty about leaving a bar bag firmly attached to the bars, and think with the small frame bag attached via the neatly blanked bosses under the top tube it’d be a pretty incredible long-distance machine. With the brand’s new integrated cockpit and aero bars, It could very conceivably be an ultra machine, especially when you consider the seatpost can be turned around to better fit that kind of riding position.

In short, it’s a hoot to ride, but given that you can configure it with so many options it is more of a versatile mile muncher than its visual package would have you believe.

Value

The spec I tested would set you back £4,973. The release of the Van Rysel RCR has somewhat upset the value apple cart, as it puts more or less everything else into the shade in terms of value. For less, (£4,500) you’re getting a WorldTour-proven frameset, Zipp carbon wheels, and a power meter. That is a bike firmly with racing in its sights, but regardless of aspirations, there is still a bit of a gulf in terms of value.

If you went for the Canyon Ultimate, similar as it is in geometry, you could get Ultegra Di2 and carbon DT Swiss wheels for about £100 less. Canyon is obviously a massive business and economies of scale come into play, but that is a big difference.

Even looking at more boutique direct to consumer brands it’s probably hard to justify from a value perspective. If you want a bike for big days out then you can kit a Fairlight Strael, perhaps the best big day out bike I’ve come across, with 105 Di2 and some carbon DT Swiss wheels for marginally less.

Not great value. Not terrible, but there has to be an amount of wanting it because you like the brand and the aesthetic I’m afraid.

Verdict

A solid bike to ride with some design features that hint at it being more attuned to big days out. Looks aero, and looks gorgeous, but there is a premium to pay for riding a little-seen cool Norwegian brand over other similarly specced options. In order to get the best out of the frameset you’re going to want slightly better (wider) wheels and tyres, which is another expense. The bike builder is pretty comprehensive though, with a very good variety of options for add-ons and fits.