There are two starting points for this ambitious show: Article 6 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and Frantz Fanon’s book, Black Skin White Masks.

The former states simply: “Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere, as a person before the law.” The latter explores the dehumanising effects of colonialism on black consciousness. Human Rights Human Wrongs is a brutal illustration of the distance between the idealism of the first and the damning evidence provided in the second.

Over two floors of the Photographers’ Gallery in London, it shows a stream of often violent images of conflict and suffering, subjugation and struggle, from across the globe. The exhibition is curated by Mark Sealy, director of Autograph ABP, from the extensive archive of the Black Star agency that was founded in 1935 in New York by three German Jews who had fled Nazi persecution.

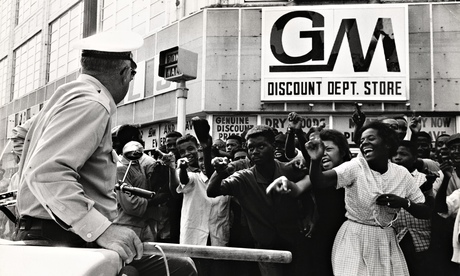

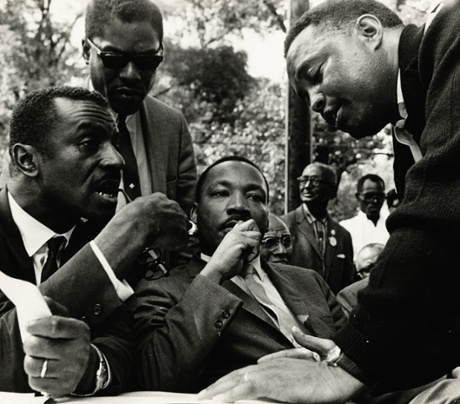

It is at times an overwhelming experience, and intentionally so. Sealy’s aim is to disrupt the received narrative of conflict and revolution, to “unhinge our so-called definitive moments and set them in a wider, more relative framework”. Thus, the American civil rights struggle of the 1960s, so evocatively captured by Bruce Davidson, Charles Moore and Dan Budnik, is mapped out here in less well-known images (though Moore is represented) and placed in the context of various 20th-century African independence struggles, in countries from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to South Africa. Likewise, connections are made between the various youth uprisings of 1968, whether the anti-Vietnam war protests across America or the student riots in Paris and Mexico City. There is much damning evidence too of the brutality with which the state responded in each instance.

Underlying this freeform approach is an attempt to interrogate both the role of the image-maker (mainly western photojournalists) and the image disseminator – mainly western media organisations. Throughout the 1960s and early 70s, Life magazine was Black Star’s most lucrative client. It accounted for nearly 40% of business and continually ran photo-stories by their best photographers, including W Eugene Smith, Charles Moore and Robert Capa, who surely brought his Black Star experience to bear when he started the legendary Magnum agency.

Bob Fitch/The Black Star Collection/Ryerson Image Centre

One of the many complex questions Sealy asks is: what does it mean for Africans, or Salvadorians or Palestinians, to have their struggles mediated almost exclusively through outsider’s eyes? And, even more problematically, how can we trust images made and disseminated within “a very particular tradition of Eurocentric concerns”?

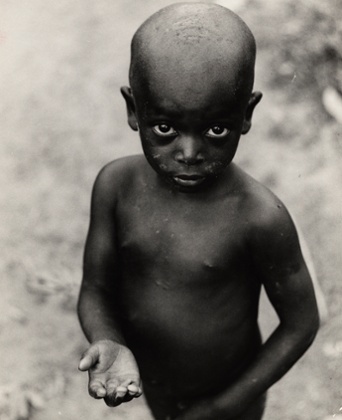

To this end, he shows how one of the defining images of famine – a starving African child, hands outstretched, big eyes beseeching – has become generic, so much so that it may have become denuded of the power to shock us. Likewise, the image of a Vietnamese or Palestinian or Cypriot mother engulfed with grief over her dead son.

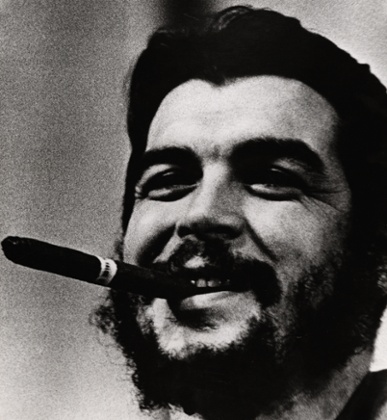

Other recurring images of conflict are selected – most dramatically the wounded western soldiers who are often photographed with arms outstretched, “framed like dying Christs on crosses” – then contrasted with the constant image of the African soldier as “a savage who needs to be tamed” or “a renegade who fights outside the rules of conflict”. As this exhibition shows time and again, from apartheid-era South Africa to the CIA-backed counter-revolutionary campaigns in Chile and Nicaragua, the rules of conflict – or democracy – are oddly elastic.

Some of this is familiar Sontagian territory, and, here and there, one longs for the rigorous analysis that underpins Ariella Azoulay’s recent book The Civil Contract of Photography, a provocative questioning of photography’s ethical and political meaning in these turbulent, image-overloaded times.

There is much that intrigues here, though, if you can spend the time picking apart the themes and catching the often sinister echoes that reverberate around these densely packed rooms. A shocking image from 1949, taken by an unknown photographer, shows two young men hanging from a scaffold in a public square in Syria. Another innocent-looking image from 1955, taken by Georg Gerster, shows a woman writing a letter beside a white picket fence in a desert. To her left, a large sign reads: Welcome to Gaza.

Both Henri Ballot and the mysterious O’Crureire (“first name unknown”) chronicled “the world’s biggest jailbreak” in Anchieta, Brazil, in June 1952. O’Cruriere’s series looks oddly unreal: every picture has been staged to resemble a scene from a classic 1940s film noir. The illusion is broken by Ballot’s dreadful image of a morgue attendant taking fingerprints from the severed hands of dead prisoners.

![HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN WRONGS Leopoldville [Young man steals the sword of King Baudouin I, during procession with newly appointed President Kasavubu], Leopoldville, Republic of the Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), June 30 1960, by Robert Lebeck](http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Guardian/Pix/pictures/2015/2/2/1422876970173/d0ff35e5-e174-48c4-86ca-20915fe0f269-460x304.jpeg)

Amid scenes of brutality, there is some breathing space thanks to several more mischievous moments of social disorder. An extraordinary sequence of photographs taken by Robert Lebeck on 29 June, 1960, the day before Belgian Congo achieved independence, shows an excited young man snatching the ceremonial sword of King Baudouin from the back of the royal car. He runs around, brandishing it theatrically, before local police bundle him into a jeep.

More fascinating still is the series of oddly intimate photographs, Vietnam chaplain, made in 1967 by William Hall “Bill” Strode III. One shows a lone soldier silhouetted against mist-covered hills; another, a wounded soldier being tended by his comrades; and yet another shows him hearing the confession of a fellow soldier. All have been written on in pencil. Above the image of the soldier confessing his sins is scrawled the line, “Why did I have to kill that guy? I didn’t know him. Why – that’s what counts?” And below, the line, “Father, after killing three gooks yesterday – I have to go to confession.”

Somewhere between the guilt, the honesty and the casual racism, which Fanon defines as one of the central dehumanising aspects of colonialism, lies the complex dynamic at the heart of this exhibition. It will make you think again about human rights and human wrongs and photography’s tricky role in reflecting – and sometimes distinguishing between – the two.

• Human Rights Human Wrongs is at the Photographers’ Gallery, London W1, 6 February to 6 April.