Caroline Darian was at home in Paris when she received a call from her mother, Gisèle Pelicot, telling her that her husband and Darian’s father, Dominique, had been arrested. The clock above the cooker had just struck 8:25 pm. Darian had been surveying the Japanese takeaway she’d brought home for dinner. It was November 20 2020.

Gisèle explained that before she and her husband set off for the police station in Mazan, Provence, that morning, they had shared an ordinary breakfast like any other. When, after a period in the waiting area, a young police officer asked Gisèle to follow him into a meeting room, she thought she would be joining her husband.

Instead, she sat alone with the officer while he showed her the first handful of the more than 20,000 photographs and videos seized from her husband’s computer. They showed Gisèle being sexually abused by Dominique and around 80 strangers while she was – to use her daughter’s words – “under chemical submission”.

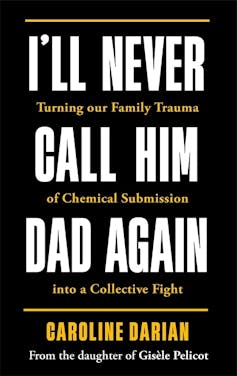

Review: I’ll Never Call Him Dad Again: Turning our Family Trauma of Chemical Submission into a Collective Fight – Caroline Darian (Bonnier)

Here began the unveiling of a profound betrayal, which would result in the 15-week trial of Dominique Pelicot and 50 other men, between September and December 2024. Most of the men came from the Pelicots’ home village of Mazan, or nearby towns and villages. They are all behind bars for sexual offences against Gisèle that took place between 2011 and 2020. Dominique was sentenced to 20 years, the maximum penalty.

Gisèle, aged 72 during the trial, refused to turn away from cameras or her supporters outside the Carpentras court in France. Four years after she was first shown the evidence of the abuse perpetrated and orchestrated by her husband, she made a public claim on her self worth. She has been lauded worldwide as a feminist hero for refusing anonymity, instead choosing a public trial in which images of her abuse were shown as evidence. And for insisting the shame of abuse must be borne by assailants, not victims.

Raising awareness of drugs and sexual assault

Her mother’s call on the day of her father’s arrest is, of course, a defining memory for Darian (a pen name), who bears “a crushing double burden” as “child of both the victim and her tormentor”. Memory is at the heart of her memoir, which she describes as a “chronicle of horror and survival”.

But the book is also a call to action, with an eye on the future. As a domestic violence researcher, currently undertaking a history of domestic violence in Australia, I know the Pelicot case raises the spectre of a form of violence rarely discussed.

In the first year of knowing her father’s crimes, Darian (a senior communications manager of a large firm in France) began to research the prevalence of sexual abuse involving chemical submission. This is known in Australia, and other parts of the English-speaking world, as drug-facilitated sexual assault. It is “the preferred weapon of sexual predators”, she writes, yet it is poorly understood, barely visible in official statistics.

Everyone has heard of GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate), the “date-rape” drug, but who is aware of the risk of being chemically subjugated by a spouse, lover, relative or friend […] with the contents of the family medicine cabinet?

In May 2023, Darian launched the movement Don’t Put Me Under, or #MendorsPas, to support victims of drug-facilitated rape and raise awareness, including among medical professionals.

“Sleeping, allergy and cough medicines are prized by abusers for their sedative and muscle-relaxing properties,” she writes. Her father used a mixture of sleeping pills and anti-anxiety drugs, prescribed for him.

She cites a 2021 French study, based on a sample of 727 complaints of sexual assault filed with police that year: 11% involved chemical submission. For over half of these victims, their assailants used over-the-counter or prescription drugs. The typical victim was a woman aged between 20 and 30. The study was undertaken by the French National Agency for the Security of Pharmaceutical Products.

The only Australian study on drug-facilitated sexual assault, published in 2006, focused on assaults committed by strangers, acquaintances and others who did not live with the victim. So, there is a lack of data. Is it an under-recognised problem in domestic and family violence here? More research is needed to find out.

Horrific truths and unmoored selves

Much of what we know about ourselves is construed by memory. Our sense of self is built on recollections of long-ago moments, vividly snagged in the maelstrom of consciousness, and our recall of recent experiences: both the ordinary and extraordinary.

Darian’s Japanese takeaway in Paris and Gisele’s shared breakfast in Mazan symbolise the final moments of the version of the two women’s lives that began to unravel that day. Darian keeps returning to the ordinariness of her parents’ breakfast: sipping coffee over newspapers, just hours before her father’s crimes against her mother would be revealed.

After that day, she and her mother try to hold onto their sense of who they are, while truths about Dominique flood in. These truths threaten to unmoor them from their memories, their shared history and from each other.

Darian’s memoir begins on the day of her father’s arrest. It spans roughly a year, finishing almost three years before his trial would begin. Written in the present tense, its series of dated entries and unsent messages to her father convey her experience with visceral immediacy. Flashbacks to childhood underline the profound dissonance between her history and her present, while revealing past clues to her father’s capacity to hurt.

One memory that now carries haunting possibilities is from August 2019, as Darian recovered from the last of three operations to work on an unexplained vaginal tear that refused to heal. Her father repeatedly contacts her, knowing she’s recovering from surgery, saying it’s “urgent”. She assumes he is checking on her health, but instead, he wants to borrow money. She is “speechless”.

An especially wrenching childhood memory, addressed to her father, reads:

You encourage me to do my first ever red ski run. You say you’ll do it with me, since I’m not a great skier […] When we reach the top of the run, you push off without me.

She follows, “terrified”. It takes her “almost two hours to reach the bottom”. Once there:

Through my tears, I yell at you for abandoning me.

The book lays bare her family’s attempts to grasp the betrayal of her father’s crimes and salvage themselves from the wreckage. Mother and daughter begin this process together, returning to the family home with Darian’s two brothers to spend one last night there. Cleaning up, throwing out and packing – but leaving with very little.

However, as more details come to light, tensions surface between mother and daughter. Gisèle seeks to re-anchor herself by finding compassion for Dominique in his jail cell. She reassures Darian he had been a good father. At one point in her journey to come to terms with what has happened, Gisèle tells her:

Your father’s in a bad way in prison. He’s suffering so much; I must have failed him in some way over the past years.

Darian recounts her “recoil”, “as if I’ve been stabbed”. But while her life is intertwined with her mother’s, it is also separate. She has a job she loves, and a husband and young child she is determined to protect from the “curse” of her father’s crimes – and those committed against him early in life.

He has said he saw and heard his father abuse his mother while her hands were tied behind her back, that he was raped during a hospital visit aged nine, and that, at 14, he witnessed a gang-rape.

‘Peering into a wall of shame’

It soon becomes apparent Darian, too, was a victim: though the extent of that victimisation is unclear. When she first sees the photographs of herself in unfamiliar underwear, in an uncharacteristic sleeping position, she doesn’t recognise herself. As these images sink in, she expresses a deep need to know exactly what her father has done to her. Gisèle refuses to believe he would harm his own daughter, and Dominique will never say.

For Darian, the way to protect the ground she stands on is to excavate the story of her own abuse and excise her father as completely as possible. Her mother’s journey is stop–start, in the face of revelations that corrupt her sense of self, built on memories of a loving marriage and family life. She requires time away from her daughter.

This causes Darian pain, but she clear-sightedly sees this temporary schism for what it is: a new violence perpetrated by her father.

Dominique pleads with Gisèle and his son Florian and accuses and scolds Darian, in unauthorised letters addressed to friends and passed on to family. But the family’s only contact with him since November 2020 has been through the courts. He and Gisèle are divorced.

In late April 2021, Darian and her mother were told by their lawyer of evidence indicating the rapes lasted longer than nine years – dating back to before the couple moved from Paris to Mazan.

Darian describes her mother in this moment as sitting “like a waxwork, no sign of life, utterly devastated. I sit next to her peering into a well of shame.” Yet, out of this nightmare, a very different image of Gisèle has emerged – dignified, strong and determined.

Medical professionals missed the signs

In the 1970s, researchers in the United States and Britain began documenting violence, including sexual violence, against pregnant women accessing antenatal services. In 1994, Australian healthcare workers were shocked by its prevalence and their failure to recognise its signs.

Gisèle Pelicot and her children spent years seeking medical explanations for her memory lapses, her slurred speech and sudden drowsiness. Gisèle had also sought medical advice about gynaecological problems.

Dominique insisted to their children that his wife was exhausted and needed to be given more space, from them and her grandchildren. Meanwhile, general practitioners, neurologists and gynaecologists failed to ask questions, or run toxicology or sexually transmitted infection tests, to investigate the possibility she was experiencing the effects of being drugged and raped.

This speaks to the absence of medical awareness of such crimes – one that exists in the wider community too. Darian’s memoir and movement aim to address those absences, educating medical professionals and others to recognise these warning signs and ask questions.

Dominique avoided raising suspicion because he and Gisèle lived alone. He perpetrated his crimes while she was rendered completely unable to object or bear witness.

Transforming trauma into activism

The subtitle of Darian’s book is: “turning our family trauma of chemical submission into a collective fight”. It speaks to the transformative power of activism. Her book is an act of solidarity with survivors, partly inspired by her admiration for others who have bravely published their stories.

The international #MeToo movement met with a range of responses in France. The Pelicot case, in which Dominique pleaded guilty (and photo and video evidence was available), is a parable about the capacity of men to exploit women. Gisèle and her daughter’s different forms of activism seek to support all victims of sexual abuse – and to encourage them to speak back to their perpetrators and the systems that burden them with shame.

In the recent history of understanding domestic and family violence, researchers have worked with survivors to identify the different forms of abuse suffered, mainly by women and children, at the hands of intimate partners and fathers. These include financial abuse, reproductive coercion and abuse, and other forms of coercive control.

This work has given us new language, and a deeper sense of the experiences of victim–survivors. It has also alerted us to newly identified warning signs.

However, little is known about the prevalence of chemical submission. Rarely diagnosed, or researched, it is neglected by the professionals and support systems supposed to help victims of abuse.

I’ll Never Call Him Dad Again teaches us about a form of violence designed to be completely hidden from its victims through total control. It is an intimate account of discovering a betrayal so profound it upends the past as well as the present. And it has alerted us to the little known or understood phenomena of drug-facilitated sexual assault within families and intimate partnerships: a form of violence that relies on complete silencing.

By telling this moving story to raise awareness of chemical submission, Darian refuses silence – for herself or her mother. In equally powerful measures, she both attests to and resists the power of this violence.

“I have tried, without success, to unearth and understand the true identity of the man who raised me,” she writes.

To this day, I reproach myself with having neither seen nor expected anything. I will never forgive him for what he did for so many years. Nonetheless, I’m haunted by the image of the father I thought I knew. It lingers on, deeply rooted inside me.

But she ends the book on a defiant note of resistance: “Faced with the unthinkable, the unbearable, we must fight back.”

Catherine Kevin (with Ann Curthoys and Zora Simic) receives funding from the Australian Council, grant number SR200200460.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.