Be it the news or the dwindling number of creatures hitting your windscreens, it will not have evaded you that the insect world in bad shape.

In the last three decades, the global biomass of flying insects has shrunk by 75%. Among the trend’s most notables victims is the world’s most important pollinator, the honeybee. In the United States, 48% of honeybee colonies died in 2023 alone, making it the second deadliest year on record. This significant loss is due in part to colony collapse disorder (CCD), the sudden disappearance of bees. In contrast, European countries report lower but still worrisome rates of colony losses, ranging from 6% to 32%.

This decline causes many of our essential food crops to be under-pollinated, a phenomenon that threatens our society’s food security.

Debunking the sci-fi myth of robotic bees

So, what can be done? Given pesticides’ role in the decline of bee colonies, commonly proposed solutions include a shift away from industrial farming and toward less pesticide-intensive, more sustainable forms of agriculture.

Others tend to look toward the sci-fi end of things, with some scientists imagining that we could eventually replace live honeybees with robotic ones. Such artificial bees could interact with flowers like natural insects, maintaining pollination levels despite the declining numbers of natural pollinators. The vision of artificial pollinators contributed to ingenious designs of insect-sized robots capable of flying.

In reality, such inventions are more effective at educating us over engineers’ fantasies than they are at reviving bee colonies, so slim are their prospects of materialising. First, these artificial pollinators would have to be equipped for much more more than just flying. Daily tasks carried out by the common bee include searching for plants, identifying flowers, unobtrusively interacting with them, locating energy sources, ducking potential predators, and dealing with adverse weather conditions. Robots would have to perform all of these in the wild with a very high degree of reliability since any broken-down or lost robot can cause damage and spread pollution. Second, it remains to be seen whether our technological knowledge would be even capable of manufacturing such inventions. This is without even mentioning the price tag of a swarm of robots capable of substituting pollination provided by a single honeybee colony.

Inside a smart hive

Rather than trying to replace honeybees with robots, our two latest projects funded by the European Union propose that the robots and honeybees actually team up. Were these to succeed, struggling honeybee colonies could be transformed into bio-hybrid entities consisting of biological and technological components with complementary skills. This would hopefully boost and secure the colonies’ population growth as more bees survive over harsh winters and yield more foragers to pollinate surrounding ecosystems.

The first of these projects, Hiveopolis, investigates how the complex decentralised decision-making mechanism in a honeybee colony can be nudged by digital technology. Begun in 2019 and set to end in March 2024, the experiment introduces technology into three observation hives each containing 4,000 bees, by contrast to 40,000 bees for a normal colony.

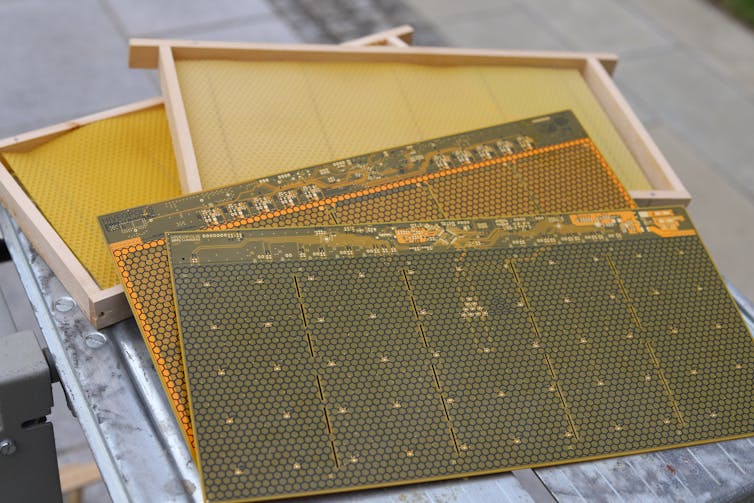

Within this honeybee smart home, combs have integrated temperature sensors and heating devices, allowing the bees to enjoy optimal conditions inside the colony. Since bees tend to snuggle up to warmer locations, the combs also enables us to direct them toward different areas of the hive. And as if that control weren’t enough, the hives are also equipped with a system of electronic gates that monitors the insects movements. Both technologies allow us to decide where the bees store honey and pollen, but also when they vacate the combs so as to enable us to harvest honey. Last but not least, the smart hive contains a robotic dancing bee that can direct foraging bees toward areas with plants to be pollinated.

Due to the experiment’s small scale, it is impossible to draw conclusions on the extent to which our technologies may have prevented bee losses. However, there is little doubt what we have seen thus far give reasons to be hopeful. We can confidently assert that our smart beehives allowed colonies to survive extreme cold during the winter in a way that wouldn’t otherwise be possible. To precisely assess how many bees these technologies have saved would require upscaling the experiment to hundreds of colonies.

Pampering the queen bee

Our second EU-funded project, RoboRoyale, focuses on the honeybee queen and her courtyard bees, with robots in this instance continuously monitoring and interacting with her Royal Highness.

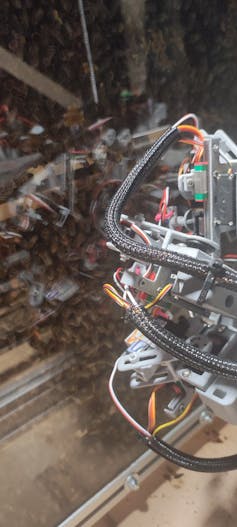

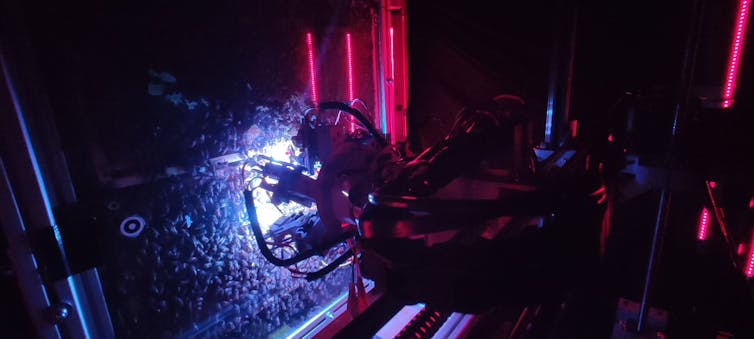

Come 2024, we will equip each hive with a group of six bee-sized robots, which will groom and feed the honeybee queen to affect the number of eggs she lays. Some of these robots will be equipped with royal jelly micro-pumps to feed her, while others will feature compliant micro-actuators to groom her. These robots will then be connected to a larger robotic arm with infrared cameras, that will continuously monitor the queen and her vicinity.

As witnessed by the photo to the right and also below, we have already been able to successfully introduce the robotic arm within a living colony. There it continuously monitored the queen and determined her whereabouts through light stimuli.

Emulating the worker bees

In a second phase, it is hoped the bee-sized robots and robotic arm will be able to emulate the behaviour of the workers, the female bees lacking reproductive capacity who attend to the queen and feed her royal jelly. Rich in water, proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, vitamins and minerals, this nutritious substance secreted by the glands of the worker bees enables the queen to lay up to thousands of eggs a day.

Worker bees also engage in cleaning the queen, which involves licking her. During such interactions, they collect some of the queen’s pheromones and disperse them throughout the colony as they move across the hive. The presence of these pheromones controls many of the colony’s behaviours and notifies the colony of a queen’s presence. For example, in the event of the queen’s demise, a new queen must be quickly reared from an egg laid by the late queen, leaving only a narrow time window for the colony to react.

Finally, it is believed worker bees may also act as the queen’s guides, leading her to laying eggs in specific comb cells. The size of these cells can determine if the queen lays a diploid or haploid egg, resulting in the bee developing into either into drone (male) or worker (female) bee. Taking over these guiding duties could affect no less than the rate’s entire reproductive rate.

How robots can prevent bee cannibalism

This could have another virtuous effect: preventing cannibalism.

During tough times, such as long periods of rain, bees have to make do with little pollen intake. This forces them to feed young larvae to older ones so that at least the older larvae has a chance to survive. Through RoboRoyale, we will look not only to reduce chances of this behaviour occurring, but also quantify to what extent it occurs under normal conditions.

Ultimately, our robots will enable us to deepen our understanding of the very complex regulation processes inside honeybee colonies through novel experimental procedures. The insights gained from these new research tracks will be necessary to better protect these valuable social insects and ensure sufficient pollination in the future – a high stakes enterprise for food security.

This article is the result of The Conversation’s collaboration with Horizon, the EU research and innovation magazine.

Farshad Arvin is a member of the Department of Computer Science at Durham University in the UK. The research of Farshad Arvin is primarily funded by the EU H2020 and Horizon Europe programmes.

Martin Stefanec is a member of the Institute of Biology at the University of Graz. He has received funding from the EU programs H2020 and Horizon Europe.

Tomas Krajnik is member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). The research of Tomas Krajnik is primarily funded by EU H2020 Horizon programme and Czech National Science Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.