From all accounts, Australia’s blue-grey mouse was a charming little creature. The famous British zoologist Oldfield Thomas of London’s Natural History Museum first described the species in 1910 and named it Pseudomys glaucus.

Within half a century, the species had seemingly disappeared, leaving behind only three scientific specimens. Since then, two of these have been lost.

But is the mouse extinct, or just extremely hard to find?

We decided to explore old museum specimens and correspondence in the hope of finding one of Australia’s most enigmatic extinct mammals. We have not rediscovered it yet – but our new research has shown us where to look.

The importance of questioning extinction

Biologists have rediscovered a number of Australian species long thought extinct. The bridled nailtail wallaby was rediscovered when a fencing contractor and his wife matched one they’d spotted in the wild to a picture in Women’s Day magazine.

The desert bettong was lost, found, and is now lost again. Gould’s mouse was found despite being thought extinct for over a century. It was hiding in plain sight thousands of kilometres away from its original range.

These efforts matter because Australia’s black book of animal extinctions has too many entries already, with 33 species of mammals lost. That’s the worst mammal extinction record in the world. Our native mice are one group suffering the most.

On the trail of the blue-grey mouse

To have a chance of rediscovery, we need to know as much as possible about distribution, habitat and the circumstances under which a species was last seen by humans.

Read more: Can we resurrect the thylacine? Maybe, but it won't help the global extinction crisis

The blue-grey mouse has a lower profile than Australia’s better-known extinctions, such as the thylacine, the Christmas Island Pipistrelle, a microbat, and what might have been the first victim of human-induced climate change: the Bramble Cay melomys.

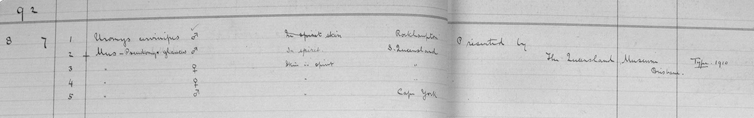

To find out more, we went back to the beginning. The three blue-grey mouse specimens Thomas examined arrived in London in 1892 as a donation from the Queensland Museum in Brisbane. The holotype specimen (an example nominated to define a species) of this mouse was amongst a group of five donated rodents. Four had originally been entered in the register as “Mus” (the house mouse genus which at the time was regularly given to unidentified rodents) from “S. Queensland” and “Cape York”.

Jotted next to the holotype was “Pseudomys glaucus” and “Type 1910”, in text that looked to have been added later. This specimen in London is now the only physical evidence we have that the blue-grey mouse ever existed. The other four rodents are missing.

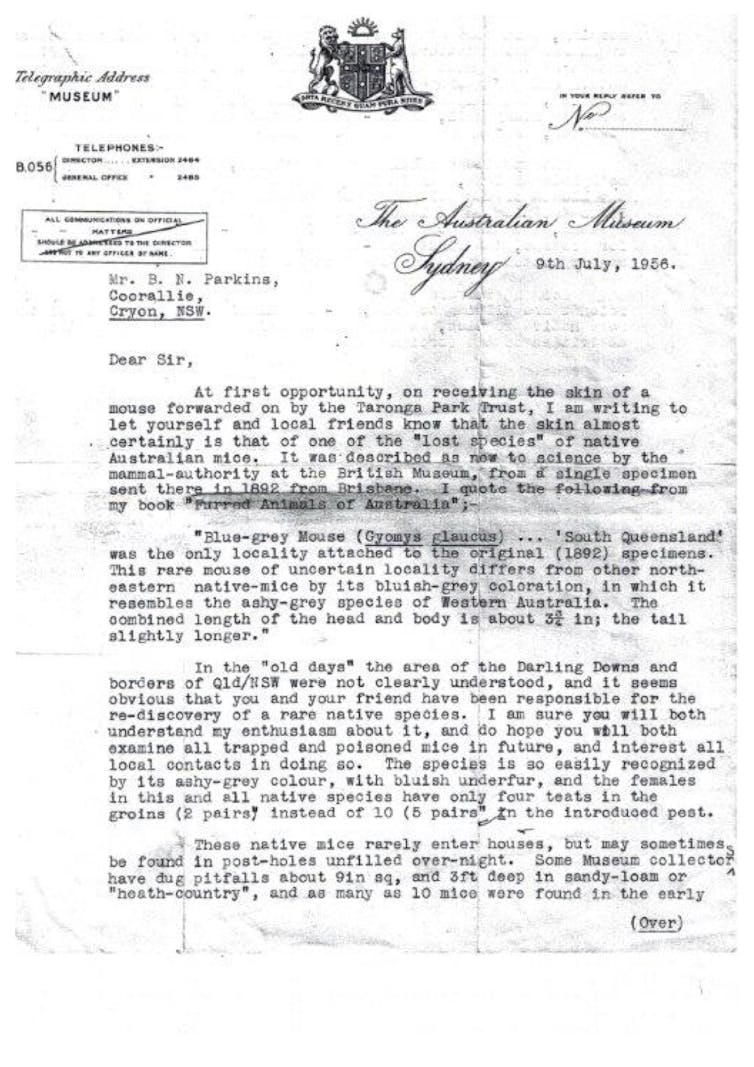

Later we found a tantalising clue to the existence of a third specimen from New South Wales in the 1957 book The furred animals of Australia by Australian Museum curator Ellis Le G. Troughton.

Here, too, the the details were frustratingly brief. A dried skin. Received in 1956 from “B.N. Parkins of Cryon”. Specimen missing.

Floods, mouse plagues and a bushie’s keen eye

We found a link between the uncommon surname Parkins and the property Coorallie at Cryon, a small region near the famous opal mining town of Lightning Ridge.

Threatened species artist and friend Penny Gale, who was originally from nearby Walgett, told us there was a Bob Neville Parkins, who lived at Coorallie and was able to put us in touch with his daughter, Jill Roughley.

Jill remembered the entire episode clearly. She had kept the original letter her father received from Troughton, the curator, thanking him for the specimen. And she remembered the circumstances of how her father found the rare blue-grey mouse.

In October 1955, record rains hit the region. By March 1956, there was major flooding. Once the rains eased, grasses and crops grew strongly. The conditions were perfect for a plague of introduced house mice.

At Coorallie, the swarms of mice broke into the stock feed rooms to gorge themselves. Desperate to keep the numbers down, Parkins set a steel drum on its end and poured grain into it to make an effective trap.

One night, a blue-grey mouse must have crept atop the drum and dropped inside. When Bob checked the trap, there it was, alongside hundreds of house mice.

Jill told us her dad was a typical “bushie”. He was acutely observant of what was happening in the environment.

Likewise, Jill recalled Coorallie in the 1950s with remarkable detail. She told us the property was on plains of native Mitchell grass, which had reached the height of a horse’s stirrups by early 1956. As the mouse population ballooned, so did their predators. Red foxes arrived in numbers, posing a major threat to the blue-grey mouse.

Jill’s memory has given us vital clues to where the mouse might still be hanging on. Mitchell grass, rural New South Wales, heavy rains. Given the mouse plagues of recent years, now might be a good time to look again.

Does one mouse species matter, amongst all the continent’s species? We believe so. And we hope the clues we’ve uncovered could see Australia’s sad list of extinctions drop by one, rather than keep going up.

Tyrone Lavery receives funding from the New South Wales Government

Chris Dickman receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

David Lindenmayer receives funding from The Australian Research Council and the NSW Government.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.