This week’s Optus outage affected 10 million people and hundreds of businesses. One of the early reasons given for the failure was a fault in the “core network”. The latest statement from the company points to “a network event” that caused the “cascading failure”.

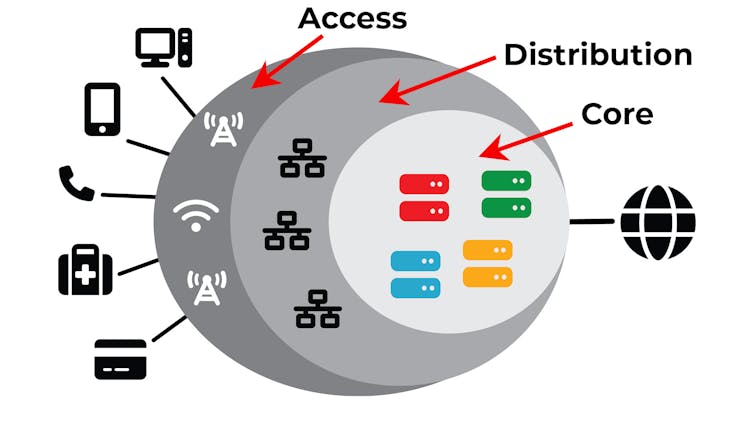

The internet is complex, so most carriers, including Optus, use the concept of the “three layer network architecture” to explain it. This abstraction splits the entire network into layers.

The access layer

This layer consists of the devices you use to connect to the internet. They include the customer equipment, National Broadband Network firewalls, routers, mobile towers, and the wall sockets you plug into.

This layer generally isn’t interconnected, meaning each device sits at the end of the network. If you want to call a friend, for example, the signal would have to travel deeper into the network before coming back out to your friend’s phone.

An outage in the access layer might only affect you and your local neighbourhood.

The distribution layer

This layer interconnects the access layer with the core network (more on that later). Remember that the access layer regions aren’t connected to each other directly, so the distribution layer is the interconnecting layer.

Another term for the interconnection cables is “backhaul.”

It is a bit more abstract but generally includes large switches in local exchange buildings, and the cabling that joins them together and to the core network.

The main purpose of the distribution layer is to route data efficiently between access points. An outage in this layer could affect whole suburbs or geographic regions.

The core layer

The core layer is the most abstract. It is the central backbone of the entire network and connects the distribution layers together and connects telecommunication carrier networks with the global network.

While physically similar to the distribution layer, with switches and cables, it is much faster, contains more redundancy and is the location on the carrier’s network where device and customer management systems reside. The carrier’s operational and business systems are responsible for access, authentication, traffic management, service provision and billing.

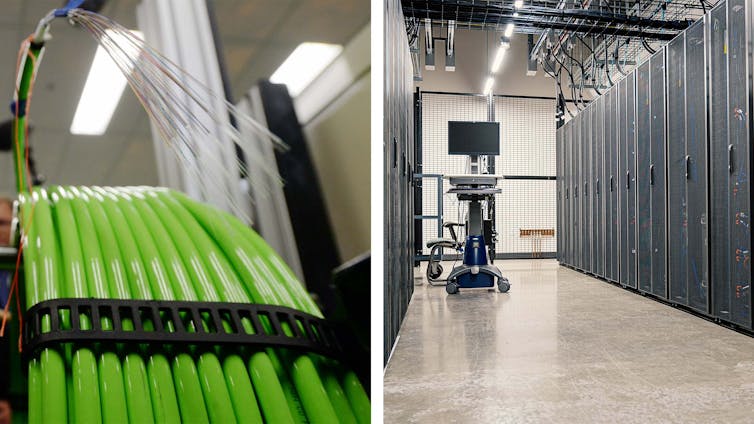

The core layer’s primary function is volume and speed. It connects data-centres, servers and the world wide web into the network using large fibre optic cables.

An outage in the core layer affects the entire country, as occurred with the Optus outage.

Why three layers?

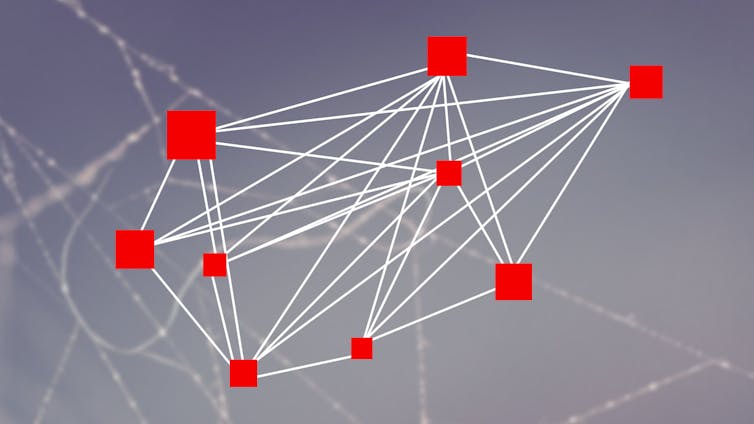

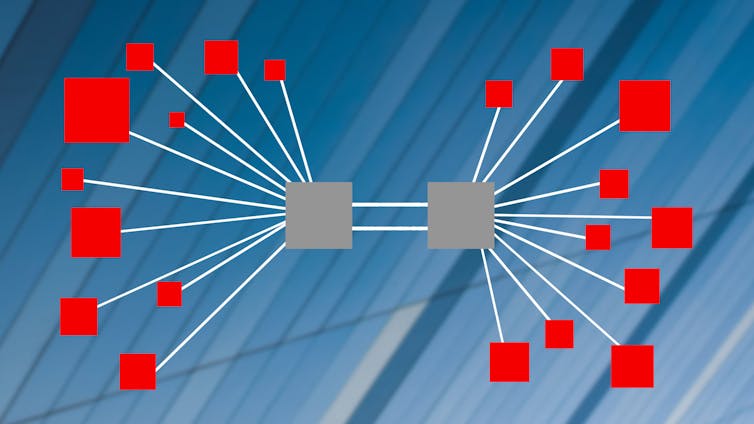

A big problem with networking is how to keep everyone connected as the network expands.

In a small network it may be possible to link everyone together but as a network grows this would be unwieldy, so the network is divided into layers based on function.

The three layer model provides a functional description of a typical carrier network. In practice, networks are more complex, but we use the three layer model to assist with the understanding of where equipment and systems are found in the network, e.g., mobile towers are in the access layer.

The core layer is designed to ensure that access layer traffic coming from and going to the Internet or data-centres is processed and distributed quickly and efficiently. Today many terabytes of data moves through a typical carrier core network daily.

Now you can see why a core layer failure could affect so many people.

Mark A Gregory does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.jpg?w=600)