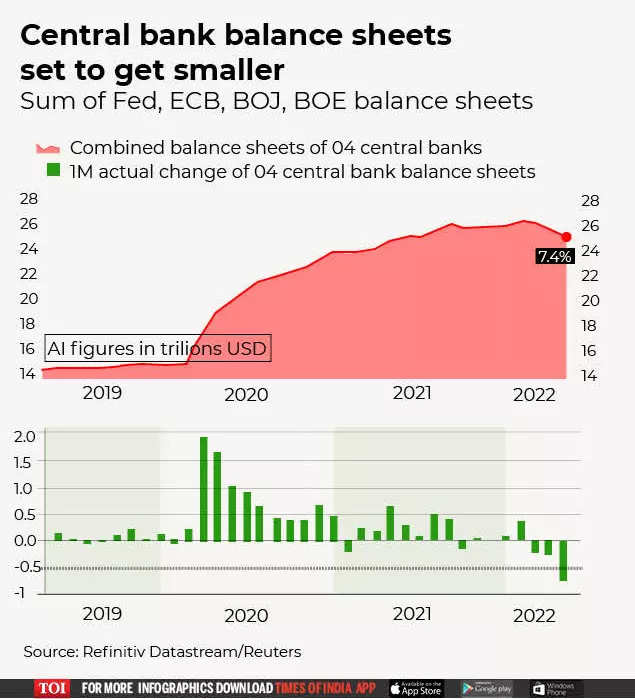

NEW DELHI: Global inflationary pressures are being faced by all economies alike. The surge in prices of key commodities has spiked more markedly and is persistent in most economies than anticipated, especially at a time when they are recovering from slowdown caused by Covid pandemic in the last 2 years.

In its recent report on World Economic Outlook, World Bank said that growth could slow significantly more, while could turn out to be higher than expected if the current global challenges continue.

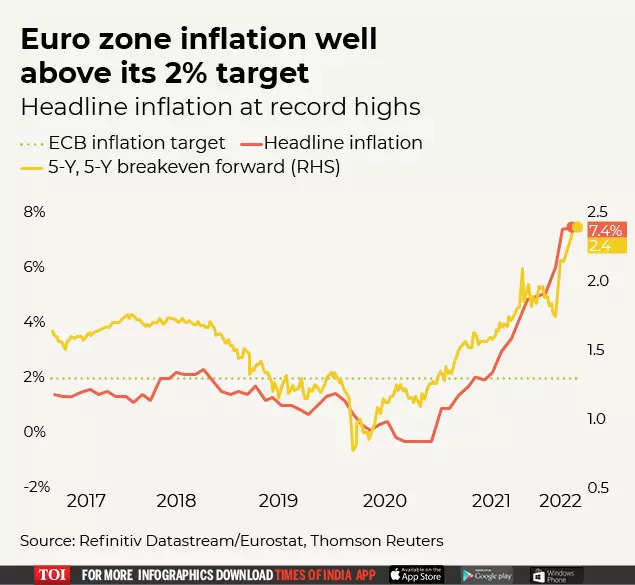

"Central banks will need to adjust their monetary stances even more aggressively should medium- or long-term inflation expectations start drifting from central bank targets or core inflation remains persistently elevated," the report suggested.

It also noted that elevated inflation will complicate the trade-offs central banks face between containing price pressures and safeguarding growth.

True to this, the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) governor Shaktikanta Das made it clear that it would be prioritsing inflation over growth in the coming months, in a bid to tame the soaring prices. .

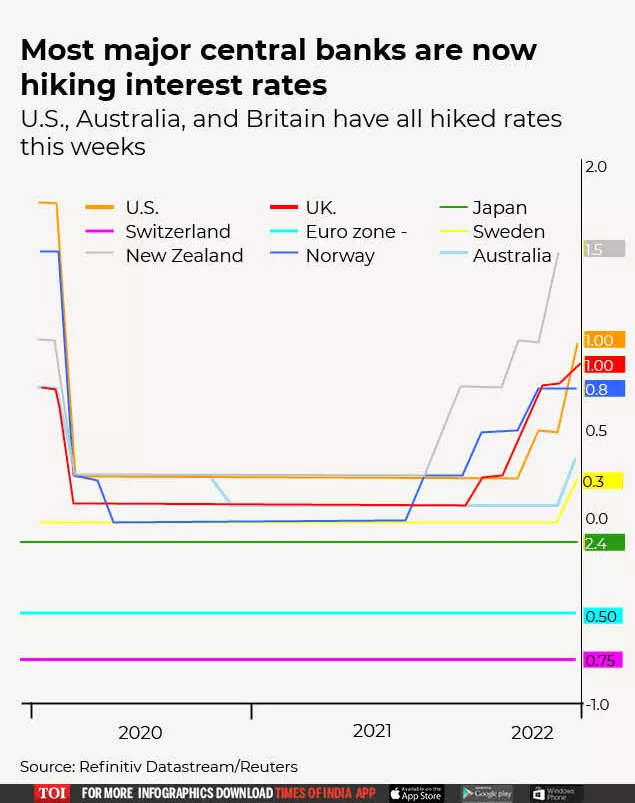

Similar stances have been observed in central banks of other major economies like the US and UK.

Earlier this week, the central banks of India and US hiked key policy rates amid persistent inflationary pressures being faced by both economies.

With this, 21 countries have increased interest rates so far in April and May 2022, a report by State Bank of India (SBI) economists showed.

Of these 21 countries, 14 countries hiked rates more than, or equal to 50 bps, the report said.

What led to this surge

The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, sanctions imposed by various countries on Russia, the pandemic and related supply chain disruptions are all major causes that pushed up prices of key commodities in global markets.

However, the transmission of war shock varies across countries, depending on trade and financial linkages, exposure to commodity price rise.

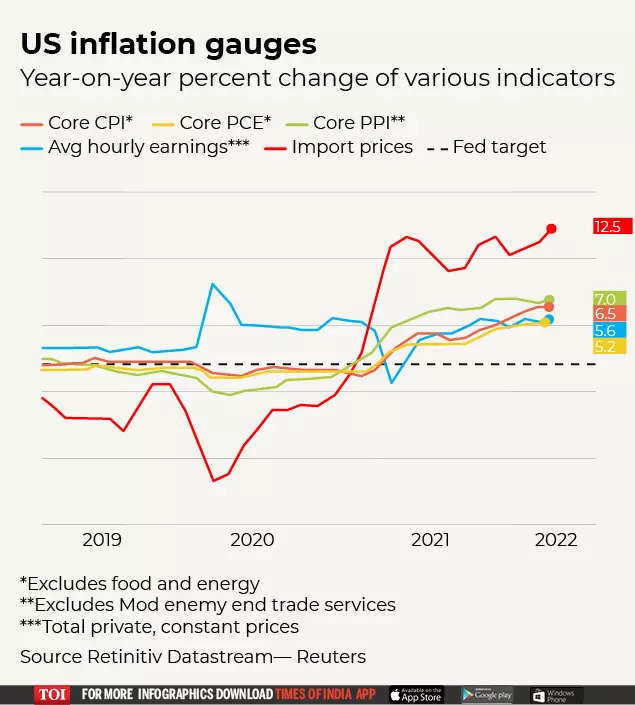

According to World Bank, inflationary pressure in the US strengthened considerably and had become more broad-based even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine—buoyed by strong policy support.

In other countries, the prominence of fuel- and war-affected commodities in local consumption baskets led to broader and more persistent price pressures.

As economies are recovering from the slump caused by Covid-19 in the last 2 years, there is also a rising concern about demand growing at a pace faster than supply, thereby, leading to demand-pull inflation.

High commodity, edible oil, metal, and fertiliser prices due to the Russia-Ukraine crisis are adding to production costs.

Here’s what central banks are doing to mitigate the impact of rising prices:

RBI hiked rates after 4 years

In a surprise move, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) hiked repo rate by 40 bps to 4.40 per cent in a bid to tame the soaring prices of goods.

In its first rate move in 2 years and its first rate hike in nearly 4 years, the RBI held an off-cycle meet to give priority to inflation over supporting growth.

Increases in fuel and food prices, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and sustained pandemic-related supply chain disruptions, have been above the RBI comfort zone of 2-6 per cent for three months in a row.

Headline inflation in March rose to a 17-month high of 6.95 per cent and it may be above the target band in April too.

The RBI also hike the cash reserve ratio (CRR) by 50 basis points to 4.5 per cent, which will now require banks to park more money with the central bank and leave them with less to loan to consumers.

This would drain Rs 87,000 crore of liquidity from the banking system, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das said in a video address announcing the rate hike decision.

The standing deposit facility rate is now at 4.15 per cent while the marginal standing facility rate and bank rate stand at 4.65 per cent.

Persistent inflation pressures are becoming more acute, particularly on food, Das said, adding that there is a risk if prices stay at this level for "too long" and expectations become unanchored.

More to follow

The central bank further stressed that monetary policy remains accommodative and will be focused on a careful and calibrated withdrawal of pandemic-related extraordinary accommodation, keeping in mind the inflation-growth dynamics.

This indicates that by the end of March 2023, repo rate may reach the level of 5.15 per cent, that is, a hike of 115 bps, the SBI report said.

Recalling that the RBI had reduced key interest rates during the pandemic by 115 bps in 2 instances - first by 75 bps in March 2020 and then by 40 bps in May 2020, the report stated that with the recent 40 bps hike the central bank has made a U-turn.

It further stated that RBI will continue to increase rate and may reach the pre-pandemic level of 5.15 per cent by end of March 2023.

The hike in CRR is expected to put further upward pressure on interest rates.

The report also said that with retail loans benchmarked to an external rate (mostly repo rate), it is expected that bank may raise interest rates by 30-40 bps.

Fed rate hike biggest in 22 years

The US Federal Reserve also raised its benchmark overnight interest rate by half a percentage point, the biggest jump in 22 years.

Fed chair Jerom Powell said the US economy is performing well, and strong enough to withstand the coming rate increases without being driven into recession or even seeing a significant rise in unemployment.

He also said that the labour market is extremely tight and inflation is too high.

Inflation in US shot up to 8.4 per cent in March, hitting a 41-year high. Inflation slowed in April after seven months of relentless gains, a tentative sign that price increases may be peaking while still imposing a financial strain on American household. Consumer prices jumped 8.3 per cent last month from 12 months earlier, the labor department data showed.

Skyrocketing gas prices have been the main reason behind the high inflation rates. Besides, increasing housing and food costs have also played a significant roles in record-breaking inflation rate.

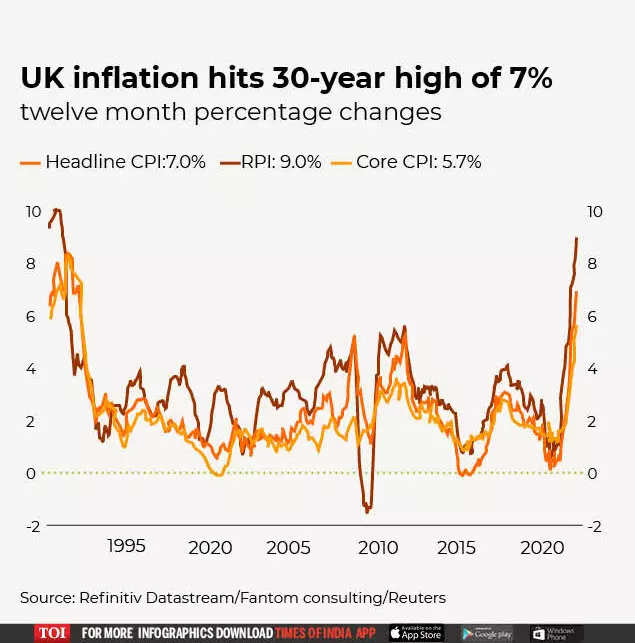

UK rates highest since 2009

The Bank of England sent a stark warning that Britain risks a double-whammy of a recession and inflation above 10 per cent as it raised interest rates on Thursday to their highest since 2009, hiking by quarter of a percentage point to 1 per cent.

British consumer price inflation hit a 30-year high of 7 per cent in March, more than triple the BoE's 2 per cent target, and the central bank revised up its forecasts for price growth to show it peaking above 10 per cent in the last three months of this year.

It had previously predicted a peak of about 8 per cent in April.

The BoE said British inflation would peak later than in other big advanced economies due to a cap on household energy tariffs. Fuel bills jumped by 54% in April and the BoE now sees a further 40 per cent increase in October, hitting the economy.

Others follow suit

The central banks of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Bahrain raised their key rates by 50 bps. The Central Bank of Kuwait said it increased its discount rate by 25 basis points (bps) to 2 per cent.

The Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) raised its repo rate and reverse repo rates by 50 bps each to 1.75 per cent and 1.25 per cent, respectively.

High inflation also prompted Iceland to lift rates by 1 percentage point, while Norway's central bank, Norges Bank, kept rates on hold on after hiking them by a quarter point to 0.75 per cent in March, when it announced plans to tighten policy more quickly than previously planned.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand raised its cash rate last month by 50 bps to 1.5 per cent, the biggest rise in two decades and the fourth hike in this cycle.

The Bank of Canada kicked off its rate-rise cycle in March, and raised rates last month by 50 bps to 1 per cent, its biggest single move in over two decades.

The Reserve Bank of Australia raised rates by 25 bps to 0.35 per cent on Tuesday and flagged more ahead.

(With inputs from agencies)