When major coal mine projects fail or close without notice, they often leave a path of destruction.

Thousands of workers are unemployed, communities left to count the environmental, social and economic cost and the whole industry and government's credibility takes a battering.

Regulation of Australia's mining industry is fractured, with different rules applying on a state-by-state and even mine-by-mine basis depending on when the mine was first approved.

Late last year, Queensland appointed its first Mine Rehabilitation Commissioner, as part of broader reforms to drive regeneration of old mine sites and create new jobs in regional communities.

Victoria has the Mine Land Rehabilitation Authority, tasked with overseeing rehabilitation planning and ensuring transition to post-mining land use.

Last year, NSW overhauled its rehabilitation laws in an effort to ensure that progressive rehabilitation is carried out throughout the lifespan of every mine.

In the Upper Hunter, 17 mines are scheduled to close over the next 20 years resulting in the release of 130,000 hectares of land and the loss of thousands of jobs.

Last month, BHP announced plans to close the state's biggest coal mine, Muswellbrook's Mt Arthur, in 2030, which employs 2000 workers.

As the global shift away from coal gathers pace, calls are increasing for major structural reform of the industry to ensure the best possible outcome for workers, mining communities and the environment.

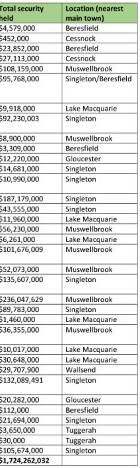

By contrast, the state government holds $3.5 billion in environmental rehabilitation bonds for all mines in the state and $1.87 billion for Upper Hunter mines.

Cooperative Research Centre for Contamination Assessment and Remediation of the Environment (CRC CARE) chief executive Professor Ravi Naidu said there was a serious shortfall between the government-held bonds and what was required for rehabilitation.

Professor Naidu, who is also director of the Global Centre for Environmental Remediation at the University of Newcastle, estimated the shortfall was more than 50 per cent.

"My feeling is the bond system is one which does not provide you sufficient funding to fully rehabilitate degraded mine sites," he said.

"I believe that within the system we should also have a research and development arm to focus on what is possible to do from a rehabilitation perspective. My feeling is, just looking at what's being spent from a rehabilitation perspective, we probably have less than 50 per cent of what it would cost to fully rehabilitate."

Professor Naidu said this opened the door for mining companies to forfeit their bonds to the government and walk away.

"It's the government, the taxpayers, who would be forced to pick up the tab," he said.

"You also have to look at the anxiety of the community members living there. On the one hand they lose their job, and on the other hand, they do not have another place to go to."

It's a criticism the NSW government flatly rejects.

A spokesman for the Department of Regional NSW said the security deposits cover the "full cost of all rehabilitation and mine closure activities" should a mining company default on their rehabilitation obligations.

"The security bond amount varies over the life of the mine, reflecting the level of disturbance and the rehabilitation obligations," he said.

"Before a security bond is returned, the mining company must provide evidence to demonstrate they have met approved rehabilitation objectives, achieved the rehabilitation completion criteria and achieved the approved final landform and final land use."

Professor Naidu said the only way to remove the concern and "stigma" about rehabilitating mine sites was to have an "exemplary site" to use as a showcase of what was possible.

He said rehabilitation work at Hunter mine sites was "hit and miss" because there was not sufficient work done by some companies prior to getting out in the field.

"We need to see what are the plant species that will grow well and what conditions do we need for them to grow well," he said.

"If we are able to do that, the investment that mining companies are making would be very, very, very worth it and the results would be much different than what we have right now."

That legacy will end in September when the mine comes to the end of its working life, resulting in the loss of 150 jobs in the Upper Hunter.

Professor Naidu said he was "comfortable" with the rehabilitation work being done at Muswellbrook Coal, but there was a lot more that needs to be done across the Upper Hunter.

In May last year, a Lock the Gate analysis of the annual reviews of four mines - Bengalla, Mt Pleasant, Muswellbrook and Mt Arthur - found the overall area of active disturbance was 2.3 times the area of land under active rehabilitation.

The average area of active rehabilitation as a percentage of the total footprint was 27.5 per cent.

Independent environmental audits for the four mines described rehabilitation efforts compromised by inadequate human resources and systems.

Poor results from drone seeding, erosion and weed infestation were cited as evidence of a lack of personnel dedicated to rehabilitation management.

At the time, a spokesman for Idemitsu Australia Resources, which owns Muswellbrook Coal, said the company regularly reviewed its rehabilitation plan to assess its progress and to ensure its environmental consent obligations were achieved.

"We are fully committed to achieving our approved rehabilitation plan and confirm that the Muswellbrook operation is currently in compliance with its regulatory obligations," he said.

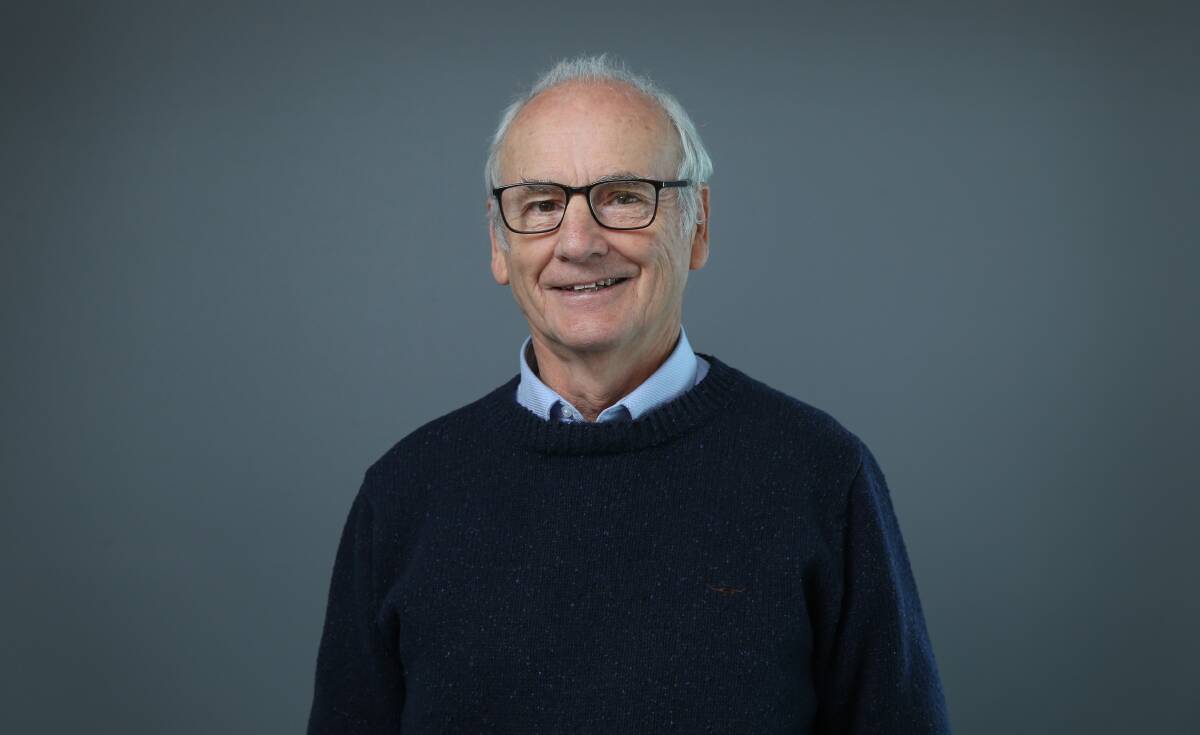

Emeritus Professor Tim Roberts, of Newcastle University's School of Environmental and Life Sciences, said an opportunity to strengthen Australia's mining industry and provide better rehabilitation and closure outcomes for communities was going begging.

Professor Roberts, who lead the university's annual Mined Land Rehabilitation conference for more than a decade as the former director of the Tom Farrell Institute for the Environment, said a national approach to mine regulation was needed.

"I would think if there was a wishlist we ought to get rid of just this state-by-state thing and have some sort of national agreement on what all mines can do, because that gives an overall better result," he said.

It's an approach that Professor Naidu, Queensland University's Dr Corinne Unger, Lock the Gate's rehabilitation specialist Rick Humphries and Murdoch University's Dr Charles Roche support.

Dr Unger, considered an international expert on mine rehabilitation and closure planning, said the federal government needed to get involved to "join all the dots".

"We sort of deal with sites one-on-one, apart from the Latrobe Valley, the rest of Australia's mines are regulated as distinct from another," she said.

"It has its own conditions applied and it has its own closure and when it was established, when it started, shapes what some of those commitments are. So they're all on a different trajectory."

However, Dr Unger said the introduction of a Rehabilitation Commissioner in Queensland last year was a sign that governments were realising the issues are more complex and connected.

"It's early days, but there's opportunities for them to facilitate research, to provide input and guidance, and connect what's going on and highlight regulatory barriers," she said.

"What's getting in the way of good outcomes? It needs to shine a light both ways, on industry as well as government, I'm not sure if that's within its scope, but it should be."

Structural reform is necessary to ensure the best possible outcomes, without creating extra regulatory burden for the industry, Dr Unger said.

It's about the federal government taking responsibility for transition, but about national coordination to "join things up and make them work".

"It's not just one region that needs regional planning to take into account mine closures," she said.

"We've got this patchwork of approaches and it needs coordination and where that coordination comes from, we should start nationally."

While some criticisms of the mining industry may be valid, Professor Roberts said the presumption that all the problems are of the industry's own making was not accurate.

He said mining companies generally did what was required of them by law and the biggest issue for the Upper Hunter moving forward was the final voids.

"If the mines show you a bit of paper that gives them licence to dig it up and leave the hole, then what can we do about it," he said.

"But social licence might change that. It might be that social pressures bring about that change."

The framework for many Upper Hunter mines was established decades ago when the mine was first approved.

Since then the communities' and environmental expectations have changed, as have technologies, rehabilitation techniques and, of course, and the legislative framework.

But the legislative structure has always lagged and, the faster the changes, the further the lag.

"Where we've got a problem is in those mines, which were allowed to commence years ago with very little end of mine regulation," Professor Roberts said.

"I'm not so happy about the planning for the voids that will be left from earlier mines, I think there has to be community agreement on what to do with them.

"The other issue is social licence, every mine is now considering its social licence to mine and that's the thing that is perhaps more variable in terms of what they need to do or think they need to do."

Professor Naidu said when open-cut mines get underway the first thing they do is remove a great deal of topsoil, or overburden.

"Here you are looking at native vegetation that has been there for many, many, many years," he said.

"It just didn't happen overnight. Therefore, when we are removing the topsoil, what we are doing is we are directly affecting the health of the soils, because the soils would have been naturally occuring."

After mining, Professor Naidu said it's a question of what state the land is returned to.

"I always ask this question, rehabilitate to what standard?" he said.

"Are we saying that we take in back to what is was before we started mining or is there a ranking index, which says, if we can bring it to a particular position, we know that over time, gradually the soil health will return to what it was and we would also have vegetation that we had pre-mining."

With different legislation applying in different states, Professor Naidu said it was a challenge because rehabilitation looks different and technology can not easily be transferred.

"Therefore harmonisation of legislation becomes quite important," he said.

As mining companies are dealing with "very degraded" soil during rehabilitation, "you just can't chuck seeds in the ground and expect them to grow".

"That's where research comes into the picture, and that component about research, it's not there," he said.

"Everybody is putting so much pressure on mining companies to go and do it, but you can't rush into it. This needs to be well planned."

Dr Unger said there were "big picture issues" that were being missed.

She said it was about "integrating the regulatory boundaries" and getting different agencies working together, but this approach would "take a lot of leadership" and the Upper Hunter was ideally placed to be a test case.

"There could be research projects done on a modified regulator arrangement where multiple agencies come together to focus on closure of a particular site to develop a new regulatory process for closure," she said.

"We need a process that brings the community and all the different agencies together that deal with land, water, cultural heritage, indigenous access to land, alternative land use planning, development and so on."

Murdoch University's Centre for Responsible Citizenship and Sustainability research associate Dr Charles Roche said "no-one has fully gotten their head around the changes coming".

"I'm not one to always argue for greater Commonwealth oversight, but at the moment there still seems to be a complete lack of recognition of the growing number and complexity and cost of mining legacies," he said.

"If the pits haven't been designed at the start to be filled in, the energy cost alone, of those mined pits, even if you had the material is pretty high. It's not something that can be easily fixed. The pollution issues coming from them alone in terms of contamination of surface and groundwater are going to be problematic."

Lock The Gate and other environmental groups have been calling for years for US-style laws to be introduced in Australia.

In the US, mining companies are obliged to return the land as closely as possible to its original form, with final voids the exception rather than the rule.

The NSW Minerals Council said the US requirement related to different mining conditions, including shallower reserves, and the comparison was not valid.

A spokesman said land disturbed by mining was progressively rehabilitated, with the objective of returning it to a safe and stable condition, consistent with the surrounding landscape.

"NSW has some of the best examples of mine rehabilitation anywhere in the world," he said.

"It is an integral component in the lifecycle of every mine in the Hunter. The mining industry in NSW takes its environmental responsibilities very seriously and works diligently to ensure the land we use is rehabilitated to provide beneficial outcomes or uses after mining is complete."

Lock The Gate's rehabilitation specialist, former Rio Tinto global adviser Rick Humphries, said because most mines still have a huge amount of rehabilitation to do, it would create a lot of jobs.

Mr Humphries said most mines had not plan for closure from the beginning, which is now considered best practice.

"At the end of the mine life, for most of the mines in the Upper Hunter, because they haven't planned for closure there's a lot of rock to move, a lot of dirt to move and a lot of work to be done," he said.

"And as we phase out, or transition out of coal, that means ironically, probably more jobs for the Hunter community in the longer term because it's going to be more expensive and it's going to take them a lot longer to get a decent outcome."