John D. Murphy, a former Catholic priest and member of the Augustinian religious order in the Chicago area, was accused in lawsuits two decades ago of sexually assaulting numerous children.

More than a dozen accusers ended up settling legal claims with the Augustinians — who oversee St. Rita High School on the Southwest Side and Providence Catholic High School in New Lenox — and the Archdiocese of Chicago over accusations against Murphy, according to interviews and records.

So why isn’t Murphy included among the 451 Catholic priests and brothers named a week and a half ago by Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul in a massive report that found the archdiocese and the rest of the Catholic church hierarchy in Illinois vastly underreported clergy members’ sexual abuse of children?

The attorney general’s office, which found nearly 2,000 child victims in Illinois by Catholic priests and brothers, won’t discuss why.

Unlike some other Catholic orders, the Augustinians — whose stated aim is, in part, to “help the restless find happiness in God” — have not made public a list of its clergy members deemed to have faced credible accusations of child rape.

That’s despite Cardinal Blase Cupich having demanded for several years that Catholic orders — which are semi-autonomous but must seek the cardinal’s approval to operate in the archdiocese, his geographic territory — come clean to him about all accusations against their members of sexual abuse.

Murphy is not on the public list of predator clergy maintained by the archdiocese, which covers Cook and Lake counties.

That’s even though the general counsel for the archdiocese, attorney James Geoly, represented the church in those long-ago lawsuits.

Why Murphy was omitted from the archdiocesan log isn’t clear. Geoly and other church officials didn’t respond to emails and calls.

Ken Kaczmarz, who was one of those who sued the church over abuse by Murphy, says: “The archdiocese, without a doubt, knew that John Murphy was a prolific child molester. They did not care then. And they do not care now.”

The archdiocese and the five other Illinois dioceses — each an arm of the church headed by a bishop — turned over names of their own abusive members to the attorney general’s office. They also were said to have turned over the names of allegedly abusive religious order members known to ever have served in their jurisdictions — if they had those names.

In some cases, they might not have had a full list of abusive members of religious orders because some orders have refused to provide those to the bishops.

And the attorney general’s office didn’t press the orders for the names of their credibly accused members, officials say.

Marc Pearlman, a Chicago lawyer who represented people who filed sexual abuse claims against the church regarding Murphy, says, “It’s my understanding that the Augustinians did not respond to a request from the archdiocese” to turn over a list of “substantiated perpetrators.”

Cupich’s office had access to the information about Murphy, too, because the archdiocese was sued along with the Augustinian order in the Murphy lawsuits, which were filed long before the cardinal was appointed by Pope Francis to lead the church in Chicago.

“They have no excuse to leave him off,” Pearlman says of archdiocesan officials. “They don’t need the Augustinians to substantiate it.”

After not responding to requests for comment, the Rev. Anthony Pizzo, head of the Augustinians for the Chicago region, emailed a statement Saturday — a day after this story was first published online — in which he did not say whether the order had cooperated with the attorney general’s investigation or answer any other questions. Pizzo acknowledged that “we have not yet published a list of those members against whom there are established allegations of abuse, as some other orders have already done.” He also wrote: “It is our sincere desire that we will be in position to publish those names in the near future.”

The Rev. Richard McGrath, another Chicago-area Augustinian who has faced accusations of sexual misconduct, also isn’t named in the attorney general’s report.

A pending lawsuit accuses McGrath of “repeatedly orally and anally” raping a Providence student years ago.

And McGrath was the subject of a criminal investigation into accusations that he had child pornography on his cell phone at the time he was running Providence Catholic High School. Government authorities investigating that wanted to examine McGrath’s phone, but it was reported to have disappeared. The investigation was closed without any charges being filed.

McGrath, who also formerly worked at St. Rita High School, couldn’t be reached.

The Joliet Diocese, which includes DuPage County and Will County, where Providence is, says in an emailed statement: “To our knowledge, all orders have been cooperative in providing information.”

Murphy, who never was charged with a sex offense, is now married and living in a senior complex in West Dundee across from a Catholic parish and school in the far northwest suburb.

In a brief interview with the Chicago Sun-Times, Murphy’s response when asked whether the accusations that he’d abused children were true was: “They’re not true in my mind.”

Murphy also said the accusations were from “40, 50 years ago.”

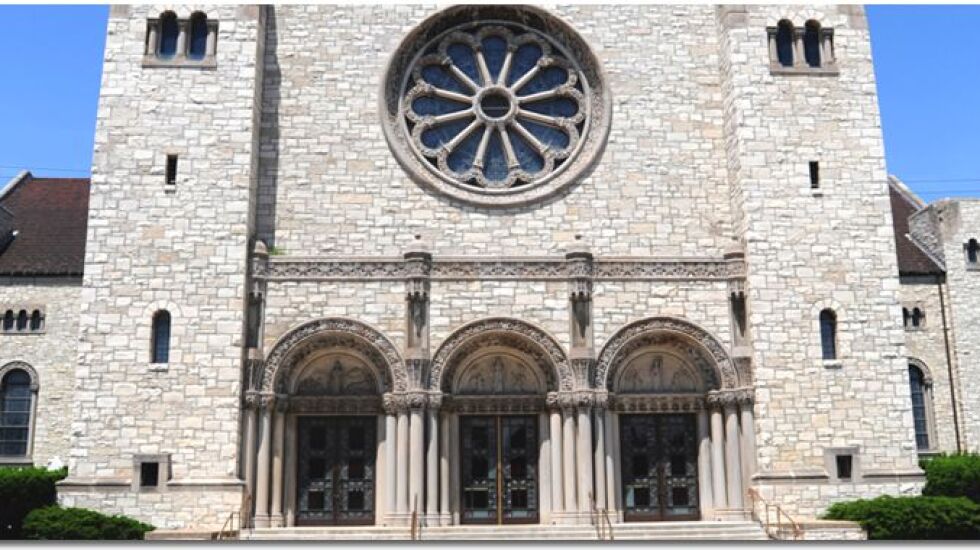

Kaczmarz says he was molested in the early 1980s, when he was a 10-year-old altar boy at St. Rita of Cascia Parish on the Southwest Side.

Most Catholic elementary schools and parishes in the Chicago region are run by priests answering to their diocese. Most Catholic high schools in the area are affiliated with a religious order.

St. Rita’s parish is affiliated with the Augustinians, who also help run St. Rita High School, two and a half miles away, where Murphy worked for years.

Kaczmarz says Murphy was once “the scheduler of altar boys” at the church and, after mass, “He’d take me into his office in the rectory, put me on his lap and squeeze me and dry hump me till he got off.

“In talking to other survivors, I know that he raped some people . . . everything from tickling to anal rape,” Kaczmarz says.

He says that two of them later killed themselves.

Though the settlements over Murphy didn’t include any acknowledgement of guilt, the Augustinians made clear at the time they viewed accusations as credible.

One of the order’s now-deceased leaders, the Rev. Jerome Knies, told the Chicago Tribune in 2004, “We’re so very sorry that anything like this ever happened in the first place, and we sure don’t want it to happen again.

“We believe we can be part of the healing process.”

The order was told at least by the early 1980s of accusations of abuse by Murphy and, according to interviews and published accounts, had him “professionally evaluated.” That process determined it was safe for Murphy to remain in public ministry.

When more sexual misconduct accusations surfaced in 1993, though, Murphy left the priesthood.

Murphy became a tour guide at the Shedd Aquarium — with the help of a reference letter from a top Augustinian order official.

Though he’d also served as a priest within the bounds of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, Murphy isn’t on its list of credibly accused clergy members, which does not include members of religious orders.