Innovator. Visionary. Modern-day guitar hero. St. Vincent has earned these accolades time and time again throughout her career. Emerging in the mid-Noughties, initially as a member The Polyphonic Spree and as a touring guitarist with Sufjan Stevens, Annie Clark struck out on her own in 2006 when she started writing music as St. Vincent and released her debut album Marry Me the following year.

Since then, her musical journey has been as thrilling as it is unpredictable. Each record gives no clues of what is to come, and with each outing, Clark reinvents herself in style and character. Playing an art-rock cult leader on her 2014 self-titled album won St. Vincent her first Grammy Award, followed up by two more wins for MASSEDUCTION’s titular single and for her 2021 album Daddy’s Home. As a collaborator, she has worked with the best, releasing Love This Giant with David Byrne and co-writing Taylor Swift’s Cruel Summer, her most streamed single to date.

In each iteration of herself, she wields her guitar as if it is an extension of herself, using the instrument to speak in a language that is felt more than it’s understood.

“Every record has its hilarity and dark nights of the soul,” she tells us when we sit down with her to take a journey through her career. Despite an advance warning that “I have not the best memory in general”, she shares memories good and bad of each of her solo albums, from near-disastrous recording sessions to the sheer joy of making art with friends, her stories as captivating as her music.

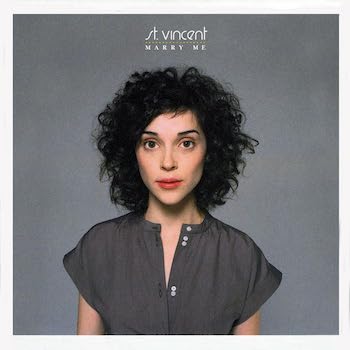

Marry Me (2007)

I remember being out with the Polyphonic Spree and the percussion player was this guy Brian Teasley, who was wild. And he was like, 'Hey, my friend has a studio in Birmingham, Alabama. Come and let’s work on this record and I’ll play drums on it.'

So I was shuttling between my home studio, which was basically my childhood bedroom with an MBOX and an Audio-Technica microphone, working on Marry Me, and then getting in my red Ford Windstar minivan and driving 12 hours east from Dallas to Birmingham. I was staying with Brian and his wife, and working at night with this engineer named Daniel Farris who lived in his mother’s basement, and had a little studio in there. Because Daniel was nocturnal, the recording sessions wouldn’t start until 7pm, and they would go through to 9 am or something. Daniel chain-smoked, so I'd walk out of there reeking of cigarette smoke.

So between doing some things in Birmingham in the basement of a completely nocturnal creature to singing songs in my childhood bedroom, some way or another Marry Me came to be.

Actor (2009)

I had toured with [singer/songwriter/producer] John Vanderslice for six weeks in the States in 2007, right before Marry Me came out. And John was such a great guy and a cool songwriter, and he has a studio called Tiny Telephone, and an engineer/producer who he worked with, Scott Solter.

So, I’m thinking I will go down to Scott’s studio in North Carolina and finish these songs. But it was clear from the moment I got there that he had... a whole lot going on. It was wild. I was staying at the house, overhearing more than I should, and it got to the point where I was scared – and by the way, this was in the middle of nowhere in North Carolina. I was there for two or three weeks thinking, I’ll get this record done., but nothing was getting done. It was just like, What is going on?

I remember walking up the dirt road, I didn’t have a car, so I was on foot, and then pacing around a church parking lot – they have a lot of churches in North Carolina – and called my friend [the Paper Chase frontman] John Congleton who I knew from working with the Polyphonic Spree. And I was like, almost in a captive whisper, John, things aren’t going very well here and I wondered if you could listen to what I’ve made and help me make some sense of it.

So I basically absconded in the middle of the night with my tapes and made it back to New York and decompressed. It was like, Let’s save these songs and get them the fuck out of there.

I went back to Texas and played John everything that I’d made and that was honestly a slow process of 1, talking me down from being vaguely traumatised from that previous experience, and then 2, just basically re-recording everything, besides all these really beautiful horn, string and woodwind arrangements that I had made, those were the only things that I kept from that session.

Very wild times. But that began my amazing, really solid run of making records with John Congleton.

Strange Mercy (2011)

Strange Mercy I wrote in my tiny, rent-controlled New York apartment in the East Village on 13th between 1st and 2nd, and I wrote [third single] Cheerleader in my bed. I think I was using [digital audio workstation] Logic at the time.

Then, when I needed to escape New York, I went to Seattle and worked out of a studio owned by Jason McGerr, the drummer from Death Cab For Cutie. I went there for a number of weeks and I wrote [Strange Mercy's first single] Surgeon out there. I was in complete isolation in Seattle, where I didn’t know anybody, really. I was staying at the Ace Hotel in downtown, in a room with a shared shower. And then I booked three weeks to go and be in Dallas, living at my mom’s house, then driving to John Congleton's studio.

Starting that process with him from the get-go was incredibly helpful, and we became, as you do making a record, really close. I would drive in my Dodge Sprinter van to South Dallas where John’s studio is, and we kept bankers’ hours, 10 to 7. There’s a specific kind of Texas Weirdo that I prize, I guess, and John is certainly a Texas Weirdo: I would hope to put myself in that category of kids who waded through all of the religiosity and the madness, throw a little bit of LSD in there. We just sat in there for three weeks and made a record. That record deals with so much pain and loss, and John really held my hand. He is so brilliant.

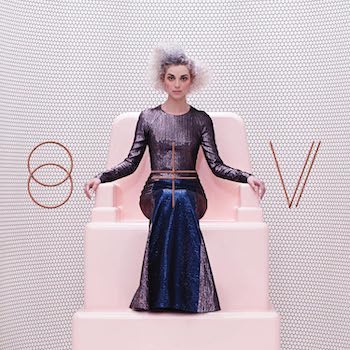

St. Vincent (2014)

I think that Strange Mercy really opened some floodgates for people. And then with 'self-titled', it was an even odder and even more confident showing. John’s sonics and mixing on it are so cool. I had just done Love This Giant with David Byrne, so I had in my head a little bit of the joy from that tour, the bounciness and the funkiness. To be honest, groove has always been so important in all my work, but I think this one was just the right amount of strange, the right amount of poppy, the right amount of heart-on-sleeve.

I wrote most of that in Austin. I rented a house and just sat there all day and wrote. And I would go and hang with my homegirls at night, and then - same deal - go to John’s, book out 3 or 4 weeks, and just make a record.

We called in some amazing players. [Funk/R&B drummer] Homer Steinweiss played on that, [Midlake drummer] McKenzie Smith played, [jazz, gospel keyboardist] Bobby Sparks, who’s such a ripper... No records I’ve ever made have been by committee, it’s a tiny little crew of people. That one resonated for a lot of reasons, but in large part due to the groundwork I had laid with previous records.

MASSEDUCTION (2017)

The Self-Titled tour took me around the world, like three times. And so many life changes happened, and I ended that run pretty much completely out of my mind. And to make MASSEDUCTION, I kind of had to claw my way, just white knuckle this music to save myself. I did a lot of the recording at my studio I built in LA, I did some things at Jack [Antonoff]’s home studio in New York, and then also at Electric Lady [in New York].

There are amazing players on it: [legendary session bassist] Pino Palladino is on it, Mike Elizondo’s playing bass. But I don’t remember so much of the making of that record, I just remember holding onto music for dear life, knowing that I needed to hold onto it, because it was going to pull me out of a certain madness.

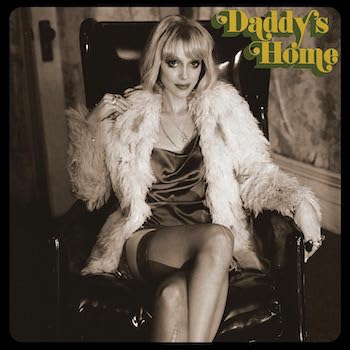

Daddy’s Home (2021)

I had met my friend and engineer Cian Riordan making Sleater-Kinney’s record, The Center Won’t Hold. So that was the start of our very fruitful relationship, and he helped me build an even better studio. With Daddy’s Home, we started it and I was maybe halfway done... and then the pandemic hit.

So everything from there on out was by proxy. Cian and I were never in the same room to mix it. Pretty wild. I did some recording with Jack [Antonoff] at Electric Lady, did some recording with Jack at Conway Studios, but then once it was lockdown, I just worked on my own and would send Jack what I had done and he would send some ideas back. We finished it basically never being in the same room.

All Born Screaming (2024)

I’ve been recording myself in my bedroom since I was 14, so it’s a very natural process for me. But I wanted to find my sound as a producer. In the same way that I have a voice as a singer, a guitar player, or a writer, I wanted to have the same level of voice as a producer. So that brings us to All Born Screaming, which was hours and hours of toiling away, alone in a room and then also bringing in some of the best people in the world.

I think the big tagline for that would just be: make art with your friends. But also, there are places you just won’t go necessarily, vocally or wherever, if you weren’t in your own world, searching, searching, searching, searching.

That is All Born Screaming A record that is about life and death and how we’re all in this together.

St Vincent plays SWX in Bristol on Friday 31st May and Royal Albert Hall on Saturday 1st June.