Dwayne Johnson has been many things. Wrestler, actor, and entrepreneur. But presidential candidate will not be one of them. After years of speculation, the Hollywood star with a reported net worth $800 million shut down rumors of ever running for office, citing family reasons.

But Johnson’s latest movie, the DC blockbuster Black Adam, brings the towering celebrity and risk-averse actor into a provocative and downright political territory.

Through the Justice Society of America — the foundational first comic book superhero “team” that predates both the Justice League and the Avengers — Black Adam broadly gestures at themes like freedom, occupation, and Western imperialism, all while set in a fictional, Egypt-like backdrop called Kahndaq.

In the end, Black Adam doesn’t try to make a point about Middle Eastern geopolitics. It’s a superhero blockbuster with Dwayne Johnson in the starring role, an actor who told Vanity Fair last year he chooses projects with “a lighter touch.” You may never see “The Rock” in a role that strays close to controversy or vulnerability, and that’s by design.

Black Adam is a contradiction of sorts. It’s big, schmaltzy popcorn fare and part of a larger superhero franchise. You can buy Black Adam-branded toys, energy drinks, and Under Armour apparel.

But Black Adam is also an anti-hero who was a slave before getting his power. In some ways, Black Adam gives Johnson a moment to tap into a darker side. The movie’s larger context of freedom and colonialism makes it one of the more daring films in the performer’s oeuvre, along with 2006’s Southland Tales and the 2013 caper Pain & Gain.

However muted the movie is in execution — it’s overblown, overproduced, and over-protective of its star — it still raises the issue of heroes as a form of foreign policy, which for a risk-averse genre feels like the movie equivalent of kicking a hornet’s nest. Black Adam isn’t strictly political, but it’s not apolitical either. And that’s a problem.

Justice for all

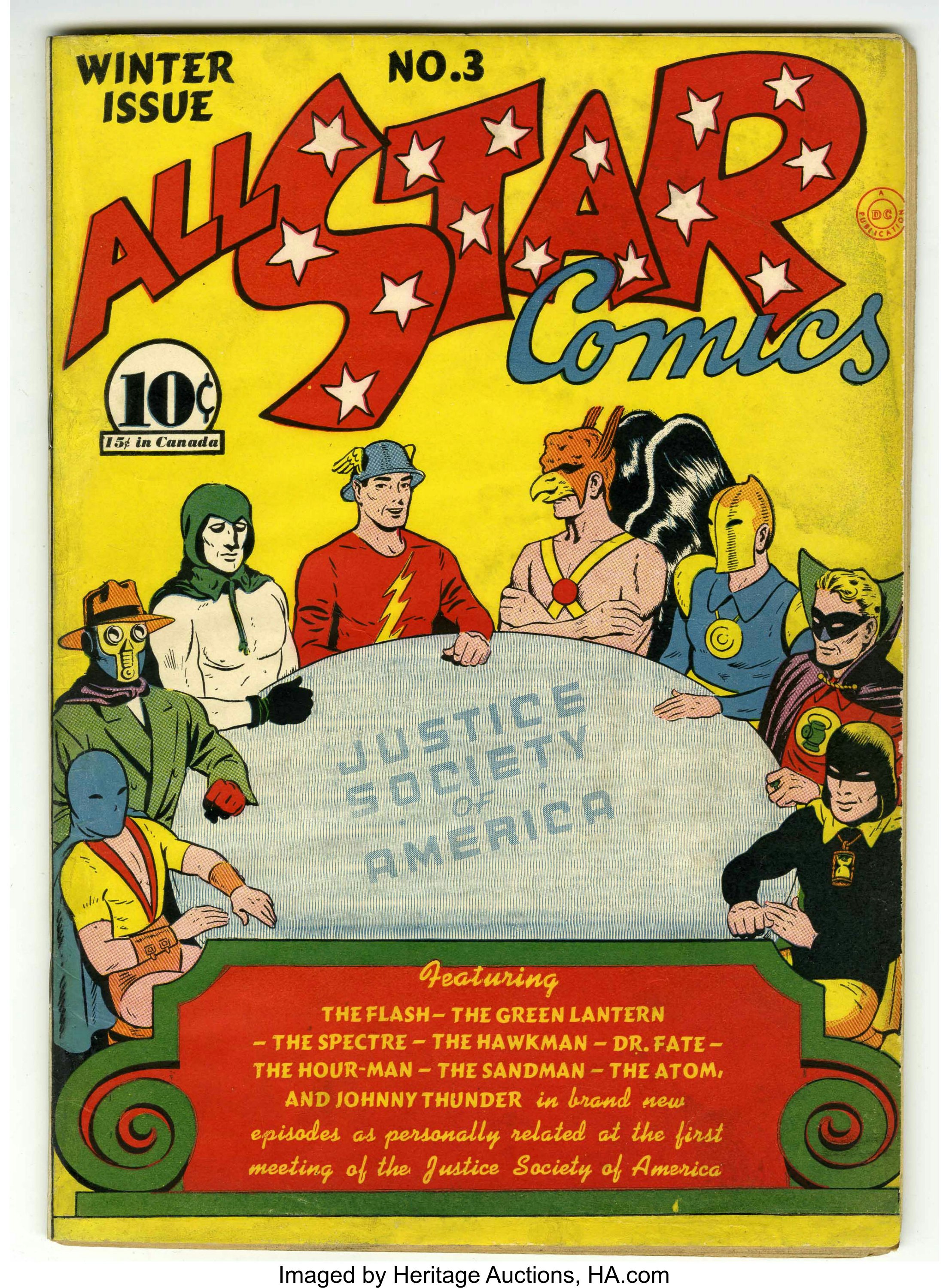

From the start, the JSA was a political unit. The Justice Society of America was first formed in 1940 on the pages of All-Star Comics #3. Their premiere “adventure” was hardly one at all, with a plot that closely resembles My Dinner with Andre than The Avengers. In the comic book’s pages, everyone from Green Lantern to the Spectre sit around a dinner table telling each other of their exploits.

It takes another issue before the JSA gets out and does stuff. At the time, the United States was ramping up to enter World War II, and All-Star Comics #4, cover date April 1941, has the JSA visit the FBI, which summoned them to “help the U.S.A. fight its internal enemies.”

In a verbose speech, the FBI’s chief tells the JSA that “a widespread, powerful organization is at work in America” plotting “to pave the way for the dictator nations who seek to overcome us with fire and sword!” The FBI chief ends his operatic monologue by declaring to the JSA: “Freedom is too precious to lose without a fight!”

The socio-cultural context that underlines these early All-Star Comics issues is simple. There was a war creeping on American shores. The rise of the American comic book industry coincided with the end of the Great Depression and the dawn of the 1940s. And so, Captain America punches Hitler in his first-ever comic, while the JSA stops the seeds of fascism being planted on Main Street.

By design, superheroes function to protect, not change, societal status quos. While their existence was to punch Nazis and ensure liberty, superheroes are a naturally fascistic archetype. And a typical afternoon for Superman is to stop bank robbers, not change the systemic failures that make desperate people turn to crime in the first place.

Black Adam and the JSA

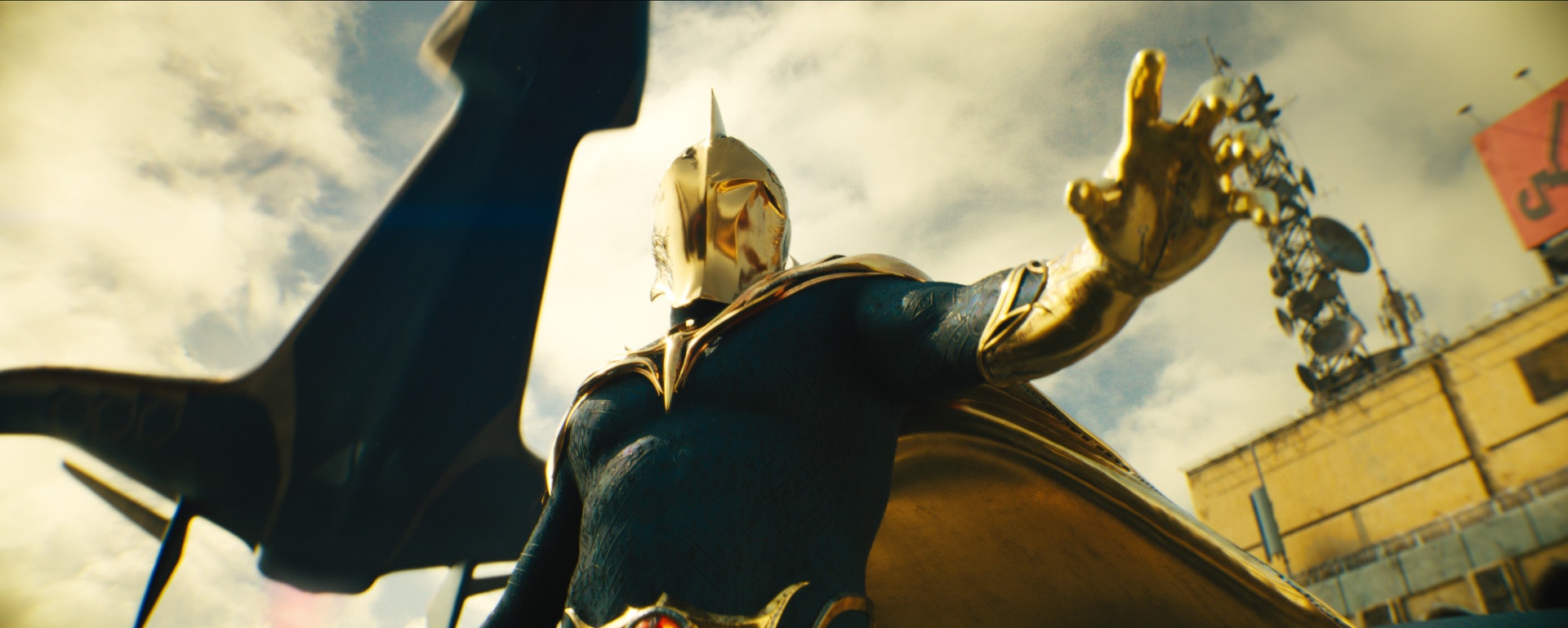

It’s telling how the JSA is deployed in Black Adam. Assembled by the nightmarish authority figure Amanda Waller (Viola Davis) who famously oversees Task Force X (aka, “Suicide Squad”), the JSA is made up of veterans Hawkman (Aldis Hodge) and Doctor Fate (Pierce Brosnan) who take it upon themselves to train the younger Cyclone (Quintessa Swindell) and Atom Smasher (Noah Centineo). Both are taking up mantles left by their grandparents, which carries an unmistakable vibe of army families whose children enroll in the same service branch.

In the film, the JSA is deployed to Kahndaq, where their presence is unwelcome. Kahndaq reveres its native hero, Black Adam, a slave named Teth-Adam (Johnson) who was gifted the powers of gods. Now that he’s returned, Kahndaq has little need for careless Westerners who wreck their shrines and statues and endanger the local populace.

The film uses the JSA as stand-ins for any polished, lawfully good heroes to contrast with Black Adam’s chaotic neutrality. But as they appear onscreen, the team also functions as a sly metaphor for Western imperialism. The JSA is slightly clumsy but overpowered. They take to the skies and mess up things down below. A more daring film would equate superhero formations to drone strikes, but Black Adam still has toys to sell.

Black Adam ultimately doesn’t say anything too specific to make a point. The film is a broad meditation on power and the responsibilities of those lucky enough to have it. If superheroes are inherently fascistic, that fact is lost in Black Adam as it reveres its title anti-hero without grilling his capacity of evil. The movie chillingly ends with Black Adam manspreading on a throne (in homage to a comic cover, but still). The scene is underscored by triumphant undertones.

Black Adam swears he’s Kahndaq’s protector and not its ruler. DC films will undoubtedly put that to the test, especially now that Superman is in the picture. As for the JSA, they’ll probably recruit more new heroes to the big screen. What that means depends on whether you think more superheroes make the universe safer or more dangerous.

Black Adam is now playing in theaters.