How much would it really cost the European Union to defend itself against aggression? In the immediate term, that question, of course makes us think of Russia, but we can no longer exclude multiple other possibilities, including the potential need to defend territory – say, Greenland – from a former ally.

How much would it cost to defend Europe if we added in the need to defend the UK, Norway, Turkey or even Canada – and any other Nato country willing to pool resources to fill the void left by US disengagement? Is there an intelligent way to avoid painful trade-offs between this and, say, spending on healthcare or education?

It looks like EU institutions are finally “doing something” (as former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi recently asked them to do). They may even break the taboo of raising common debt in order to increase spending on joint defence procurements.

Yet, it also seems they are about to launch a plan that could change the very nature of the European Union without even tackling the question of its financial feasibility. The answer to how joint defence can be paid for certainly didn’t come from the previous President of the Commission’s statement on “rearming Europe”. At the very last line of that statement, a figure of €800 billion is posited, but it is not clear how the sum was calculated and quite a few critical qualifications are missing.

The debate over how much it costs to prevent a war (which is a very different notion from fighting one), has been dominated by what I would call “the fallacy of the percentage of GDP”.

In 2014 (at the time of Russia’s annexation of Crimea), the leaders of Nato countries agreed to spend at least 2% of their GDP on defence (specifying that retirement benefits to veterans should be included). Yet by 2022, the overall ratio for Nato defence spending had, in fact, shrunk from 2.58% of GDP to 2.51% (thanks to the sharp reduction in the percentage of GDP contributed by the US). And, according to the European Defence Agency, the EU is spending around €279 billion, which is 1.6% of its GDP. Most likely, the €800 billion figure that European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen was citing in her communique is simply an estimate of how much it would yield to increase that spending up to 2% of GDP for each of the next ten years.

Politicians sometimes need to make back-of-the-envelope calculations, but I would argue that here it points to a much broader problem. Europe hasn’t yet bothered to try to develop a strategy for how this additional money would be spent. A proper strategy should, in fact, start from three key technical considerations. To which I would add a no-less important political one.

1. Spending smart is better than spending big

Technologies (including AI) are radically changing the equation. The conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza demonstrate that cheap drones are now the key to modern warfare – not super expensive F35 strike fighters. Why spend billions designing, building and maintaining 2,500 F35s when a drone the size of a mobile phone can cross enemy lines unnoticed?

In a world in which data is a weapon, and a large-scale attack can be mounted by taking remote control of pagers, what generals call “supremacy” doesn’t necessarily belong to the biggest spender.

Israel’s military budget is one-third that of Saudi Arabia, yet it dominates the Middle East because its perpetual state of conflict forces innovation. Russia spends less than half of the 27 EU member states, but it has much more experience in hacking other countries’ infrastructures. The EU spends as much as China, but China invests more than twice in research and development and is the world’s largest exporter of drones as a result.

2. Spending together is better value

The European parliament estimates that merging the 27 member states’ defence budgets would free up €56 billion (which is a third of what the defence bonds proposed by the Commission would raise).

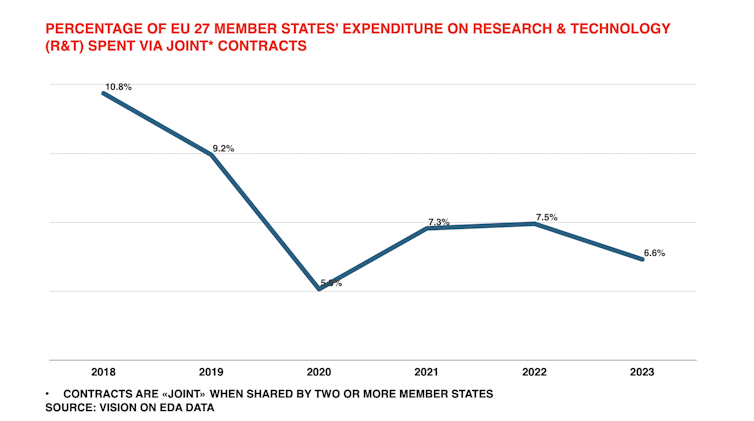

Yet the trend is to spend more alone than together. According to the European Defence Agency, the bloc has more than doubled its expenditure on new digital technologies; yet the percentage of that going into joint projects between member states fell from 11% before Ukraine’s invasion to 6.5% in 2023.

3. Homegrown suddenly looks safer

Any common defence would also have to rely on “buying European” as much as possible. The F35 fighter jet is another good example here. Denmark agreed to buy 27 of them (to the tune of around €3 billion) with an idea to station four of them in Greenland. The problem is that, according to the former president of the Munich security conference Wolfgang Ischinger, they cannot even take off if remotely disabled by the US. Again, Europe is not walking the walk. The share of equipment that European nations import from the US has massively increased in the last five years.

A new era for the union

Defence is probably the most important issue when talking about the Europe of the future. It provides a concrete opportunity to fill a technological gap out of the necessity to do so. Spending on defence in the interests of self-protection may have longer-term benefits beyond the military arena. It has been often the case that military research leads to major breakthroughs that can applied in public services. Who knows. Military innovations with drone or AI technology on today’s battlefields could lead to beneficial uses in peace time.

The historic opportunity to transform the way we protect ourselves may even force a radical rethinking of not just the EU treaties but of the nature of the EU. The idea of the “coalition of the willing” may, indeed, push Europe towards an alliance which does not include some of its members (such as Hungary) but does include non-members like the UK, Norway and even Turkey. New arrangements will need to be pragmatically flexible.

Europeans need much more strategy, whereas we now largely have rhetorical announcements with little substance. And we need much more democracy. After all, defence is one of the defining dimensions of the state. Having a common defence policy in Europe could make people feel more like European citizens. But that cannot happen without engaging citizens in an intelligent debate.

Francesco Grillo is affiliated with the think tank Vision.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.