Russia’s war against Ukraine has led some EU countries to reassess use of anti-personnel mines leading to the prospect of their re-introduction to Europe after a long-standing ban under the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention.

Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland have all recently announced their plans to withdraw from the treaty, which prohibits the use, stockpiling, production, and transfer of anti-personnel mines.

The treaty was agreed in 1997, since when 164 states have signed it including all EU member states as well as most African, Asian, and American countries.

The 33 states which haven't signed up include China, India, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Russia, South Korea and the US along with several Arab countries.

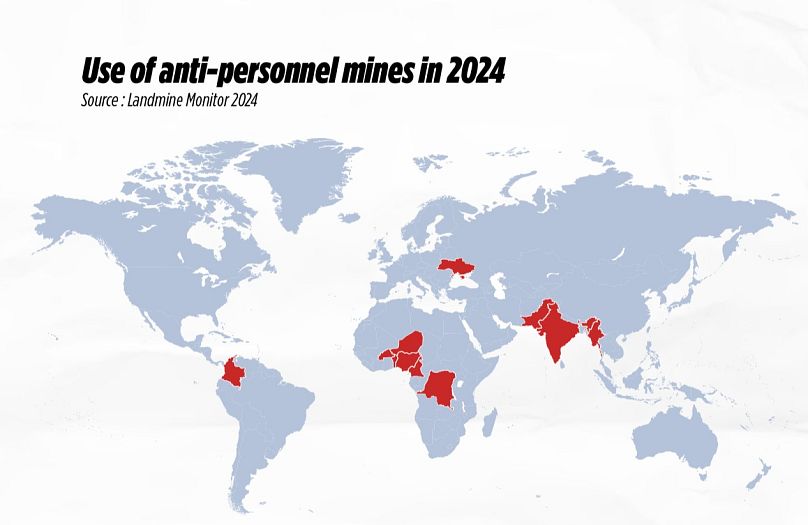

Anti-personnel mines were widely used around the world in 2024, according to the Landmine Monitor 2024 report, published by the International Campaign to Ban Landmines – Cluster Munition Coalition (ICBL-CMC).

In some cases, national armies or government forces have used them, such as Myanmar, which has deployed them since at least 1999, and Russia has made extensive use of them in its invasion of Ukraine, turning the country into the most heavily mined in the world.

Anti-personnel mines are also often used by non-state armed groups. This was the case in 2024 in Colombia, Gaza, India, Myanmar, Pakistan, and probably also in Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, Niger and Nigeria, according to the report. At least 58 countries around the world are currently contaminated by anti-personnel mines.

A 'weapon from the past'

“We know that over 80% of the victims of anti-personnel mines are civilians and especially children,” Gilles Carbonnier, vice president of the International Committee of the Red Cross, told Euronews.

He considers anti-personnel mines “weapons of the past”, since they principally kill and maim civilians and have little military effectiveness.

“First, they often harm the army's own side, their own soldiers or friendly forces. Second, clearance is extremely costly and takes a long time,” he said, adding that Croatia has not yet cleared the last remaining mines from the Yugoslav Wars of 35 years ago.

According to Landmine Monitor 2024, anti-personnel mines caused 833 casualties in 2023, the highest annual number recorded since 2011.

But beyond fatalities, anti-personnel mines leave behind a long trail of wounded and mutilated, according to Socialist Italian MEP Cecilia Strada, former president of the NGO Emergency, which was founded by her father in 1994.

“I saw the first person injured by a landmine when I was nine years old. Then I counted hundreds of them,” she told Euronews, recalling her past experiences in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, and Cambodia.

Civilians are the main victims—84% of all recorded casualties, according to the statistics—because mines remain in situ long after conflicts end. “In Afghanistan, I saw children stepping on landmines put there by Russians who had left the country 15 years before,” Strada said.

Women and children are most affected in her experience. “What happens in a war-economy, or a post-war economy? Men are at the front, or wounded, and so they can no longer bring home the bacon. So women and children graze sheep, take water from the rivers, cultivate the land, and go to collect metals.”

“Banning anti-personnel mines is quite obvious,” she states, recalling EU law and the Geneva Conventions on humanitarian law. “But now, in Europe, we are going down a slippery slope.”

The plans of EU countries

Defence ministers of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland issued a joint statement to explain their recommendation to withdraw from the Ottawa Convention, citing a “fundamentally deteriorated security situation” in the Baltic region.

Contacted by Euronews, Estonia’s Defence Ministry said that “there are currently no plans to develop, stockpile, or use anti-personnel mines.” However, with this decision, the four Baltic countries are sending a clear message, as they write in the statement: “Our countries are prepared and can use every necessary measure to defend our territory and freedom.”

Finland’s defence minister also explained the decision by stating: “Withdrawing from the Ottawa Convention will give us the possibility to prepare for the changes in the security environment in a more versatile way.”

Latvian government was even more outspoken in its answer to Euronews: "War in Ukraine has shown that unguided anti-personnel landmines, in combination with other mines and weapon systems, increase the lethality of defence forces by delaying or stopping Russian military mass movements".

The Latvian Parliament will take the final decision on whether the country shall withdraw from the Ottawa Convention and Latvia does not currently plan to produce or transfer unguided anti-personnel mines to Ukraine.

On the contrary, use of landmines is not ruled out: "In our opinion, anti-personnel mines can be used, to disperse enemy forces or channelize and direct it to deny terrain to the enemy that cannot be sufficiently defended", reads the government's statement to Euronews.

The European Union’s institutions are broadly in line with these plans, despite the EU’s position on the topic being very clear: “Any use of anti-personnel mines anywhere, anytime, and by any actor remains completely unacceptable,” reads the official document on the ban against anti-personnel mines, adopted in 2024.

Asked by Euronews during a press briefing, the European Commission stopped short of condemning the decisions of the five Baltic member states.

“We have contributed over 174 million since 2023 to humanitarian mine action, including 97 million euros specifically for mine clearance,” recalled Commission spokesperson Anouar El Anouni, without commenting on the withdrawal plans.

The topic was included in the European Parliament's annual report on the “Implementation of the Common Security and Defence Policy” voted on in April in Strasbourg.

An amendment that “strongly condemns the intention of some member states to withdraw from the 1997 Convention” was rejected by a show of hands. Another motion, tabled by the European People’s Party and approved with 431 votes in favour, essentially justifies the steps taken by the Baltic countries and blames Russia for them.

But Russian threats do not justify EU countries responding in kind, Gilles Carbonnier told Euronews.

“International humanitarian law and humanitarian disarmament treaties apply precisely in exceptional circumstances of armed conflict, in the worst of circumstances. And international humanitarian law does not rest on reciprocity, because this would trigger a downward spiral,” he said.

Moves such as these by EU countries could provoke a domino effect, he claimed, sending a “negative signal” to those countries around the world that are in armed conflict but are still adhere to the convention.

“They might say: ‘Why should we continue to adhere to that treaty?’”