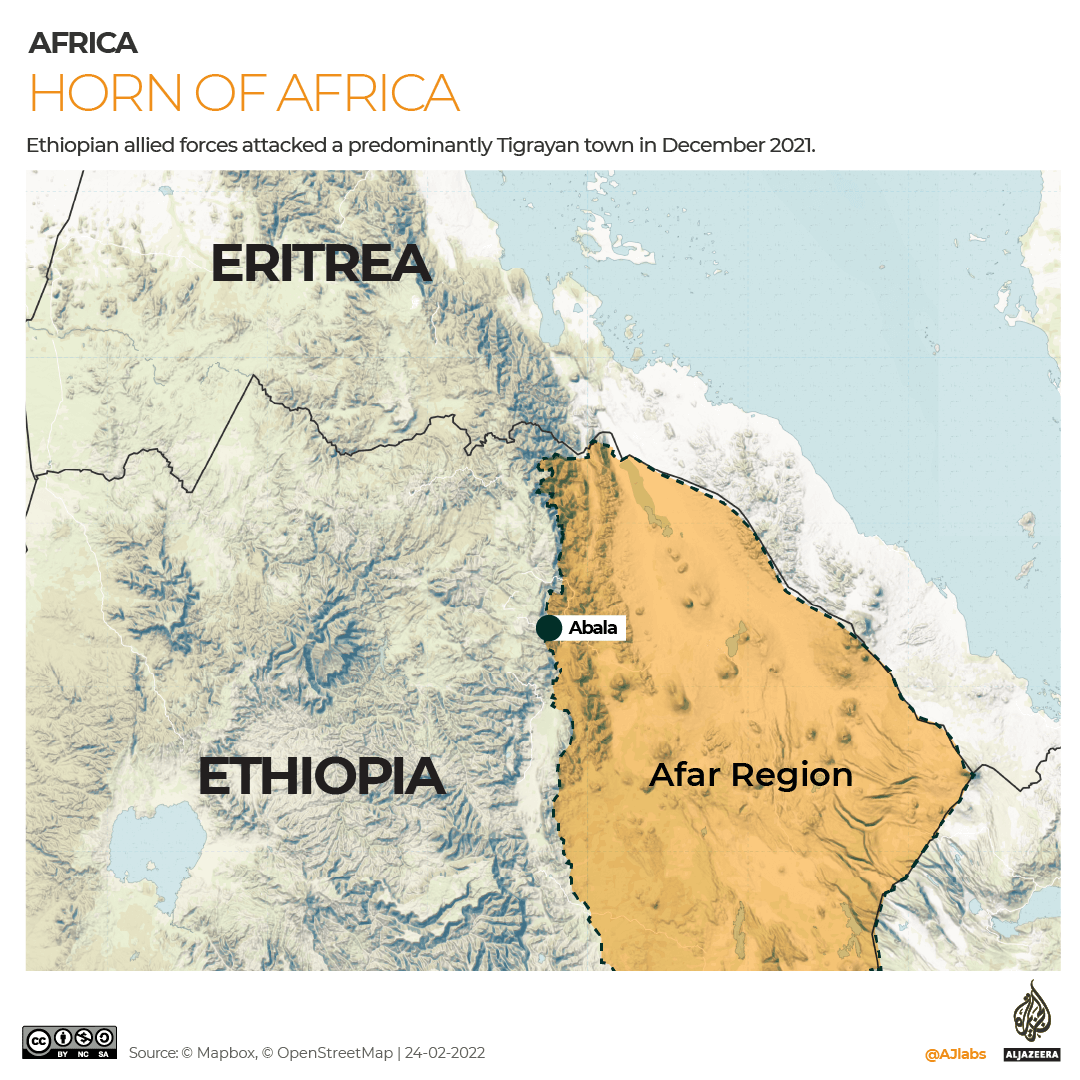

Desta Gebreananya remembers seeing hundreds of bodies littered all over the street – young men, children and even pregnant women – on December 24, 2021- just days after Ethiopian allied forces raided her hometown of Abala in the Afar region.

The 41-year-old and her five children were fleeing the community, which is at the border between the Afar and Tigray regions, after hiding for a week in the house of a neighbour, an ethnic Afar. They walked on foot for three days and then paid smugglers to cross into Tigray.

“They [soldiers] protected civilians of other ethnicities and erased the Tigrayans,” said Desta who now lives in the Derg-Ajen camp for internally displaced people (IDP) on the outskirts of Mekelle, the Tigrayan capital. “They killed, gang-raped, looted and arrested every Tigrayan they found in the town. Only if you knew an Afar to either hide you or help you escape, could you be saved.”

She still does not know whether her husband, who went missing in the melee, is dead or alive.

In the camp, there are almost 7,000 people who fled from Abala to Tigray in late December, including 26 girls who reported cases of sexual violence. The survivors, mostly women and children, are currently sheltered in four IDP centres including Derg-Ajen, all located on the outskirts of Mekelle.

As part of its investigation, Al Jazeera obtained testimonies from dozens of them. “They exterminated us all,” Desta said. “No Tigrayans are left now in the town. They committed genocide against us.”

In November 2020, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed sent troops to the Tigray region to remove the northern region’s governing party, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, from power accusing it of attacking a military base.

Since then, thousands have died and more than nine million people are in need of urgent humanitarian intervention in a conflict that has escalated to neighbouring regions of Amhara and Afar.

Ethiopian federal forces and allied troops have been accused of weaponised sexual violence, mass detention and summary executions. As the conflict escalated to Amhara and Afar regions, the Tigrayan forces have also been accused of abuses against civilians.

In June 2021, Eritrean troops retreated from much of Tigray when the rebel forces captured most of the region from the Ethiopian federal army. But Eritrea has since renewed its military partnership with the regional forces of Afar, one of nine regional states in Ethiopia, which is next door to Asmara.

Witnesses say the collaborative efforts between Ethiopia and its allies led to an attack on Abala, a community of predominantly Tigrayan people, in December. The invading military battled Tigrayan forces all of December [18], leading to the latter’s retreat from the area.

In the interregnum, the allied forces killed unarmed Tigrayan civilians; witnesses presented Al Jazeera with a list of 278 people they had confirmed dead. Fifteen survivors also recounted how Afar militiamen and Eritrean troops went from house to house, seeking Tigrayans out in a killing campaign that continued over five consecutive days.

“They came to our neighbourhood at midday as I was baking injera in the back yard,” says Asay Teka, another survivor from the IDP centre of Lemlem. “They shot my husband and 11 other Tigrayan neighbours they found around,” she said. “Among them were four boys under the age of five, killed alongside their parents.”

For the next five days, Asay hid in her house, staring at her husband’s corpse and praying the soldiers would not return. When the bloodletting slowed down on December 24, she fled.

A new proxy front

“[This] is part of the anti-Tigray pogrom and calculated ethnic cleansing by Ethiopian, Eritrean and Amhara forces in a new proxy front,” said Mehari Taddele Maru, a human rights lawyer and professor at the European University Institute in Florence. “These forces see the Afar region as the latest proxy war route, and it could quickly become the battleground for a web of conflicts that is likely to rage for years.”

As many as 90 per cent of residents in the Afar region are ethnic Afar, but the town of Abala is an outlier with Tigrayans accounting for almost 70 per cent, according to local administrators.

In August 2021, the Tigrayan forces were accused of murders and other atrocities in other towns in the Afar region, like Galicoma.

Last December, the United Nations Human Rights Council passed a resolution to establish an independent investigation into violations committed by all warring parties in the ongoing conflict. Ethiopia’s government objected to the resolution, calling it an “instrument of political pressure”.

Since June 29, all communications to the Tigray region have been blocked. Al Jazeera reached out repeatedly by email to the spokespeople of the Ethiopian prime minister’s office and Eritrea’s information minister Yemane Gebremeskel for comments. Neither responded.

However, Al Jazeera managed to contact survivors on the ground and gathered firsthand evidence of the massacre, including graphic footage of bodies and mass burial. One witness saw hundreds of bodies collected with a bulldozer and dumped in far-off craters.

Witnesses also gave the name of Memher Tekeste, a 51-year-old teacher who was killed together with 16 members of his extended family on December 21. Their bodies were dumped in a crater named Mai’shegola. Survivors gave a list of other victims and described similar cases of targeted killing of entire families to Al Jazeera.

“They were barging into houses, looting and gang-raping girls as young as nine,” said Hareg Tekelu, another resident of the IDP centre of Mekane’ Kidusan. She fled Abala with her three-year-old daughter.

Tekelu said the people who hid her, told her that the troops forcefully loaded hundreds of Tigrayans into trucks and headed towards detention camps in Semera, the Afar capital, on December 22.

“The continuing conflict between the troops is creating ruptures of socioeconomic ties between these neighbouring people,” said Kjetil Tronvoll, head of Oslo Analytica consultancy firm and professor of peace and conflict studies at Bjørknes University College. “Elders on both sides need to be engaged to try to prevent unnecessary civilian casualties and displacement.”

Desta and other survivors in the IDP centres consider themselves lucky to be alive and see no future in the past they escaped from. “Seeing what I have seen, I have nothing left to go back,” she says.