On the morning of June 12 1962, a loud, shrill siren began wailing from the top of a rock in San Francisco Bay.

Few, if any, had ever before heard it sound in anger. It was the escape siren on the supposedly inescapable island prison of Alcatraz.

Fifty-six years ago on Tuesday, an early morning bed check revealed that three inmates were missing from their cells.

In their place were towels and clothes arranged to resemble bodies sleeping under blankets, with dummy heads made from a mixture soap, toothpaste, concrete dust and toilet paper, topped with real human hair taken from the floor of the prison barbershop - not overly realistic, but enough to fool the guards who had checked on the cells during the night.

A massive manhunt began, involving federal agents, state and local police, coastguard boats, military helicopters and at least 100 armed troops.

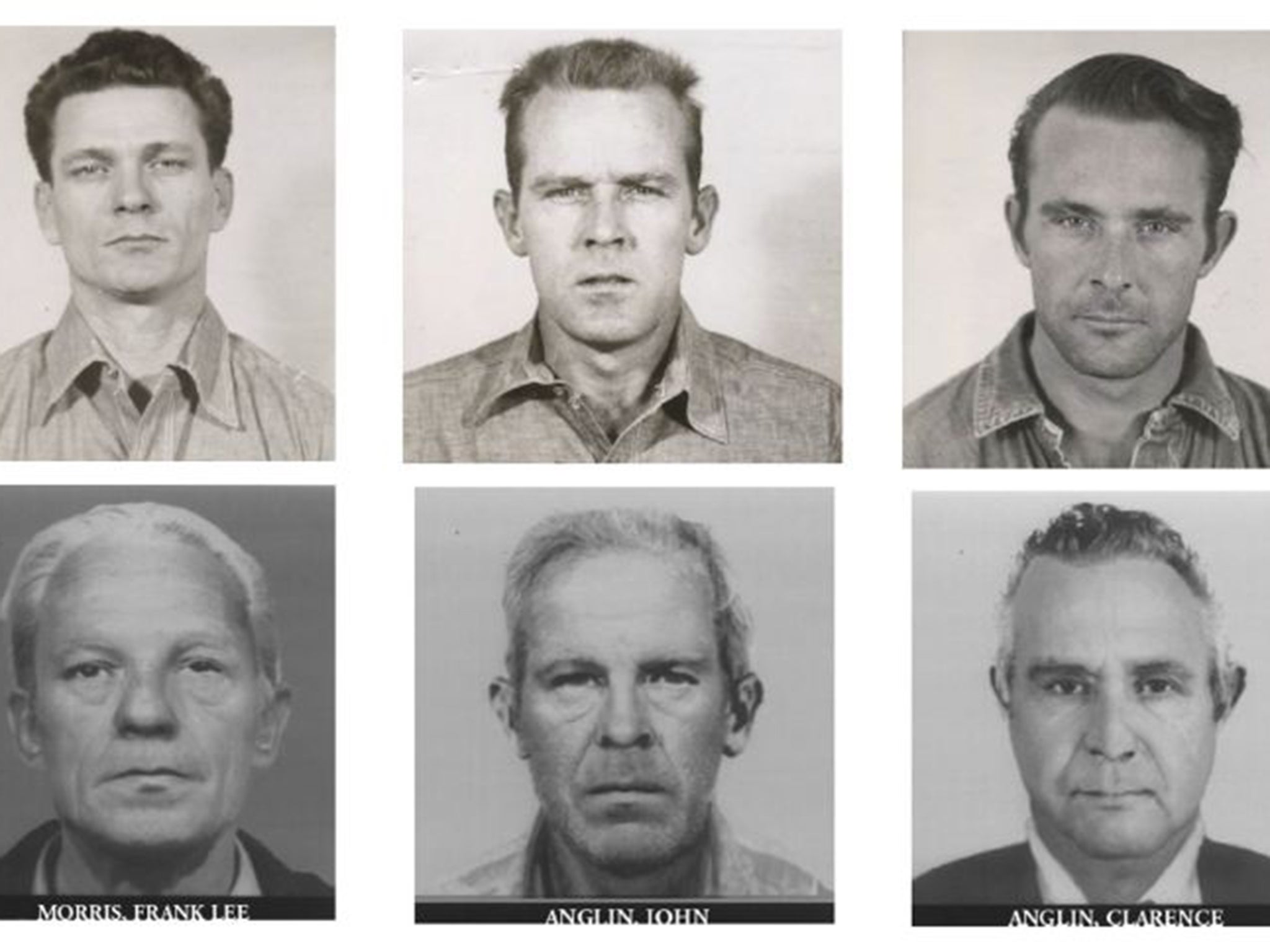

But Frank Morris and the brothers John and Clarence Anglin were never found – by officialdom.

And so a trio of convicted bank robbers became folk heroes.

Even today their legend lives on. Some wonder whether the men themselves do too.

There is only a faint chance of all three still being alive now – Morris would be 91 today, John Anglin 88 and his younger brother Clarence 87.

But since the escape, there have been reports of the Anglin brothers sending their mother Christmas cards, of Frank Morris meeting a cousin in San Diego, of the trio sending fellow inmate Clarence Carnes, the Choctaw Kid, a postcard with the ‘mission accomplished’ code phrase: “Gone fishing”.

The escapees’ reputation was perhaps burnished by repeated official insistence that they had drowned trying to escape. It was definitely enhanced by the Clint Eastwood film Escape from Alcatraz – released in June 1979, six months before the FBI closed its case and declared the three men dead.

If the authorities really had refused to believe the men made it out alive, that would hardly be surprising.

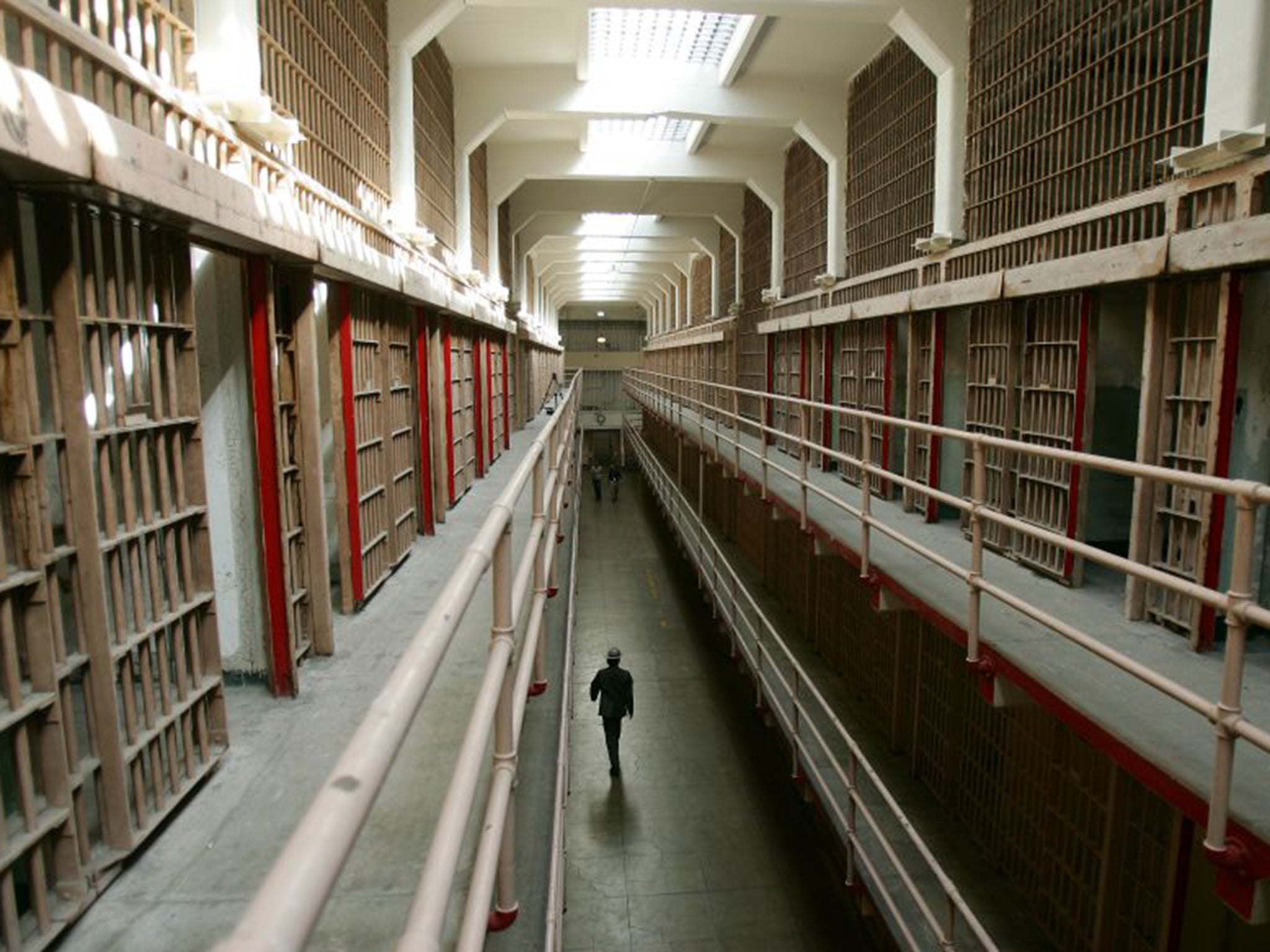

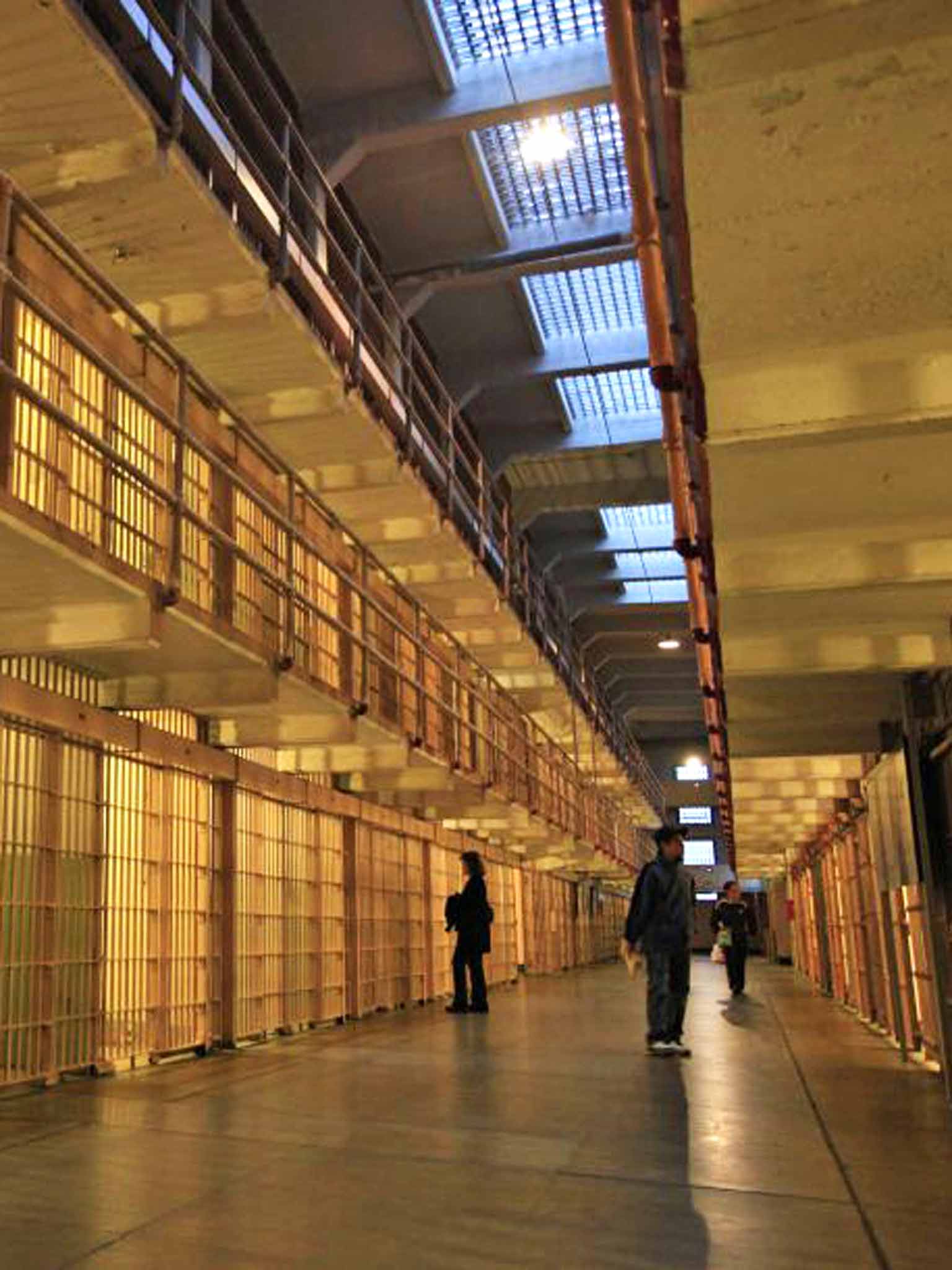

Alcatraz was the prison within the prison system, the place reserved for the trouble makers, or those who refused to stop trying to escape or to run their criminal empires from behind bars.

You didn’t escape, although - until they were abandoned in 1941 - you might go mad in the solitary confinement dungeons of what was initially a 19th century military prison.

The only normal exit routes were death or infirmity – the latter was how Al Capone eventually got out, in 1945, so riddled with syphilis that he was deemed incapable of running his gangster empire from behind the bars of a softer jail.

At Alcatraz, natural barriers enhanced human security that included 12 head counts a day, prison guards listening to every contact with visitors, and metal detectors so sensitive they were set off by a stay in Al Capone’s mother’s corset.

The prison may only have been 1.5 miles offshore, but, especially to prisoners allowed little or no exercise, it had the potential to be a fatal swim.

The water was often bitterly cold and rough. There were strong currents and lethal undertows, although the talk of “shark-infested waters” is something of an exaggeration.

Prison folk tales told of ‘Bruce’, a shark bred by the Bureau of Prisons to have only one fin, and thus forced to swim in perpetual circles around the island.

In truth, the sharks in the bay are normally leopard sharks – not man eaters, although they were scavengers capable of “cleaning up” the corpse of any man who drowned trying to escape.

Thirty-six prisoners tried to get out during Alcatraz’s 29 years as a civilian penitentiary, between its opening in 1934 and its closure in 1963.

Six were shot and killed trying to escape, including the first inmate to make an attempt, Joe Bowers, on April 27 1936 – although since he chose to climb the fence in full view of the guard towers he may have had suicide, not absconding in mind.

Twenty-three of the 36 would-be escapers were recaptured alive. Two were found dead and drowned.

That leaves five escapees out of the 36 unaccounted for: the 1962 trio, and robbers Theodore Cole and Ralph Roe, who used a hacksaw blade to get out of their cells on December 16 1937.

They too were subject to the authorities’ insistence they died, swept into the vastness of the Pacific Ocean by 7-to-9-knot tides, on a day so foggy any would-be helpers would supposedly have been unable to find and rescue them.

They too were subject to persistent rumours they had survived, in one account sending Alcatraz Warden James A. Johnston a postcard every year.

But they didn’t get the Clint Eastwood treatment.

Many details of Morris and the Anglins’ escape were gleaned from the man who had intended to join them: under-educated car thief Allen West.

He, like them, had widened the ventilation duct opening in his cell wall. But unlike them he had used a cement to shore up concrete that was crumbling around his painstakingly widened exit hole. On the night of the escape, he found his cement had set, and by the time he had widened it enough to get out, he found that the others had gone on without him.

West returned to his cell, and went to sleep – and in return for not being punished for his escape attempt, he told investigators all.

And so we learned how for six months, the escape had been meticulously planned by Morris, a man orphaned at 11 and first convicted at 13, but with an IQ in the top two per cent of the US population. He was played by Eastwood in the film.

The four men widened the vents in their 5ft by 9ft cells using canteen spoons, discarded saw blades that they had found in the prison grounds, and a drill they made from the motor of a broken vacuum cleaner.

They used the playing of Morris’ concertina to drown out the sound of their work, and hid the visible signs of what they were doing by making papier-mâché ventilation duct grilles using magazines from the prison library.

The dummies were first used to convince guards they were sleeping, while in fact they had left their cells for night-time visits to a secret workshop on the cell block roof, accessed via the holes in their cells, an unguarded utility corridor and plumbing pipes that they used as steps.

On the rooftop, they secretly made life jackets and a 6ft by 14ft (1.8m by 4.3m) life raft out of 50 stolen or donated raincoats. The raft could be inflated using Morris’ concertina. The design was said to have been based on an article they saw in a copy of Popular Mechanics magazine in the prison library.

On the night of June 11, they waited until the 9.30pm head count, before all but West successfully made it up to the cellblock roof.

From there, they accessed a higher roof via a large ventilation shaft. The guards actually heard a large crash as the three men got out of this shaft, but disregarded the noise after hearing nothing further.

Taking their home-made raft with them, the three convicts were able to shimmy down a large exterior pipe to the ground, before cutting through the barbed wire at the top of the perimeter fencing.

Some time after 10pm, they slipped away from Alcatraz, heading through dense fog to their first objective, Angel Island, two miles to the north.

From there, according to West, they had planned to cross to the mainland, pilfer clothes to replace their prison uniforms, and steal a car to make their getaway.

But according to the FBI, despite the huge attention the escape generated, no such crimes were reported on the mainland at the relevant time.

Even with a raft, the crossing to the mainland would have been a hazardous undertaking.

What is more, the FBI has said: “If the escapees had help, we couldn’t substantiate it. The families appeared unlikely to even have the financial means to provide any real support.”

“For the 17 years we worked on the case,” the bureau concluded, “No credible evidence emerged to suggest the men were still alive, either in the U.S. or overseas.”

Some reports seem to support the suggestion that the three men had drowned, their bodies being swept away into the Pacific Ocean, or disposed of by scavenging sharks.

It has been stated that three bodies in some sort of uniform were spotted by fishermen off Bolinas, outside the Golden Gate, which fitted with some estimates of where the tide would have carried Morris and the Anglins.

In 2012 it was reported that about one month after the jailbreak, the crew of a Norwegian freighter passing through the ocean about 15 nautical miles from the Golden Gate Bridge had spotted a body floating in the sea wearing a navy coat and light trousers that resembled Alcatraz prison uniform.

And yet.

The US Marshals Service, which took over the case when the FBI closed its file in 1979, has not completely given up. It has publicly stated it will “continue to pursue the escapees until they are either arrested, positively determined to be deceased or reach the age of 99”.

The Alcatraz to mainland swim is potentially treacherous, but it can be done – if you know where to start from.

The Escape from Alcatraz Triathlon now takes place every year, in early June, and involves a swim that starts near Alcatraz Island.

Professional swimmers, though, tend to start from the east side of the island, not the west, where there is the worst undertow and from where some analysis suggests Morris and the Anglins set off in their raft.

That said, one Alcatraz inmate is known to have survived the swim. In December 1962, six months after the Morris and Anglins’ escape, John Paul Scott was found near rocks beneath the Golden Gate Bridge.

Admittedly, hypothermia and exhaustion had reduced Scott to such a state of collapse that the teenage boys who found him thought he had attempted suicide by jumping from the bridge. Nonetheless he was still alive (albeit returning to Alcatraz via a short stay in hospital).

Various teams of documentary makers or academic researchers have also attempted to model or reconstruct the Morris and Anglins escape and found it to have been theoretically survivable, if the convicts entered the water at the right time.

And in 1993 John Twomey, acting director of the US Marshals Service, told the US TV show America’s Most Wanted: “We know they [Morris and the Anglin brothers] were young and vigorous, that they had the physical ability to survive and that they had a well-thought-out scheme.”

The same TV programme featured the claims of former Alcatraz inmate Thomas Kent who said he had helped plan the escape, despite not daring to participate because he couldn’t swim.

Kent suggested the men had the assistance of an Anglin brother’s girlfriend, who had agreed to meet them on the mainland shore and drive them to Mexico.

There was some official scepticism, however, much of it centred around claims that Kent had been paid $2,000 for the interview.

Over the years there have been plenty of stories that have that kind of flavour – great scoop if true, possibly flaky or ultimately unprovable.

There have been reports of deathbed confessions, from a dying man telling his nurse he and an accomplice had picked the three escapees up in a waiting boat, combined with the testimony of an off-duty cop who recalled seeing a vessel that would have matched the description given.

Then there was the poor quality photo “of the Anglin brothers in Rio de Janeiro in 1975” that surfaced in a 2015 – possibly genuine, although the man who supposedly took the snap has also been described as a “drug smuggler and a conman”.

The same 2015 a History Channel documentary featured Christmas cards signed in what seemed to have been the Anglin brothers’ handwriting and said by the family to have been received by their mother for the first three Christmases after their escape. Investigators matched the handwriting but were unable to be certain about the dates.

One of the more promising leads came in 2011. Deputy US Marshal Michael Dyke, of Northern California, who is indisputably knowledgeable since has been assigned to the case since 2003, revealed to a National Geographic documentary that in 1962: “Some teletypes [teleprinter read-outs] indicate there was possibly a raft recovered on Angel Island…the day after the escape – and one of them mentioned footprints leading away from the raft.

“They came across an oar, a paddle…right off the coast, about 50 yards from the shore of Angel Island.”

That still left the convicts – or the only one of them left alive to make footprints - with the task of getting from Angel Island to the mainland, although the documentary also suggested that, contrary to FBI assertions, a car had been stolen in the right sort of area on the night of the escape.

But possibly the most intriguing clue of all came just five months ago, in January 2018.

It was in the form of a handwritten letter, reportedly sent to the San Francisco Police Department in 2013 but only obtained by the local TV station KPIX 5 five years later.

“My name is John Anglin,” the letter began. “I escape from Alcatraz in June 1962 ... Yes we all made it that night, but barely!”

The letter writer said Morris had lived until 2005 and Clarence Anglin had died of natural causes in 2008.

‘John Anglin’ – if it really was him – wrote that he had spent many years living in Seattle, before passing eight years in North Dakota and latterly settling in Southern California.

Now, the 2013 letter writer claimed, he was “83 years old, in bad shape” and looking to cut a deal with the police.

“I have cancer,” the letter stated. “If you announce on TV that I will be promised to first go to jail for no more than a year and get medical attention, I will write back to let you know exactly where I am. This is no joke.”

An FBI laboratory examined the letter for its handwriting and for fingerprint or DNA evidence. The results were “inconclusive”.

But the Anglin brothers’ nephew David Widner revived the family tales of two fugitives who had sent messages to their mum.

Mr Widner talked of his grandmother receiving roses and a signed card for several years after 1962.

And he suggested that if they had got out of Alcatraz alive, John and Clarence Anglin would not have repeated the follies of their criminal youth.

“I think that Alcatraz was probably a huge learning lesson for them,” said Mr Widner. “I don’t believe that had they made it out of there that they would have risked committing any more crimes to get caught, to go back to Alcatraz.”

So maybe they did survive – although one small irony is that if Morris and the Anglins had just waited, they wouldn’t have needed to risk their lives escaping from Alcatraz.

The institution closed as a prison on March 21 1963, less than a year after the escape. The walls were beginning to crumble – this time through natural decay rather than prisoner action – and the then attorney general Robert Kennedy ruled that the upkeep of the jail had become too expensive.

A greater irony is that Alcatraz is now a tourist attraction, meaning that by escaping from it, the Anglin brothers and Frank Morris probably did more to promote the place than any others – except, perhaps, Clint Eastwood.