The silent Grundig wireless sets, empty wine bottles and tired musical instruments made for diverting lunch decor in Ghibabo. Young men and women at a neighbouring table chat, taking in the eccentricity of this restaurant and pizzeria in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea.

“Ethiopian people,” says a nearby diner, pointing at a nearby group. “Tourists.”

After a protracted independence war and 20 years of unresolved border conflict, a peace agreement between Eritrea and Ethiopia was signed in July. Ethiopian Amharic voices are still a novelty in Asmara.

Eritrea lies at the Horn of Africa, bordering Sudan and Djibouti. Its 1,000km Red Sea coast faces strife-ridden Yemen, and curtails port access for Ethiopia. Asmara recently acquired Unesco status for its legacy of Italian modernist architecture. Mussolini envisioned Asmara at the heart of Italy’s new African Empire; an aspiration never achieved.

With its broad, tree-lined Avenue Harnet, downtown Asmara is a city with lungs. Beyond the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, Rosina Caffé’s glass-panelled doors open onto busy marble-top tables. Cappuccino, macchiato and gelato are served by uniformed waitresses. Avocado juice is available – perhaps a nod to Asmara’s burgeoning hipster scene? But this is no overpriced expatriate bolthole. Customers are Eritreans, mostly older men, and save for the absence of wifi it could be southern Europe.

Across the road it’s possible that Cinema Impero’s art deco façade makes more of a statement now than it did in 1937. Though the list of showings – mainly Korean martial arts movies – says something too. Reflecting on lengthy conflict, Asmarinos have had their fill of real fighting. Elsewhere, faded pastel streets reference Africa and Italy in unhurried homage to daily life. “Don’t worry, there are no thieves in Asmara,” remarks a café manager when I carelessly abandoned my shoulder bag.

Eritrea’s second city, descending from Eritrea’s cool central plateau, is Keren. It’s 90km north west of Asmara, but seems further. I arrived in the warm evening air and a power cut had cast downtown into darkness. Generators clatter into life: business as usual.

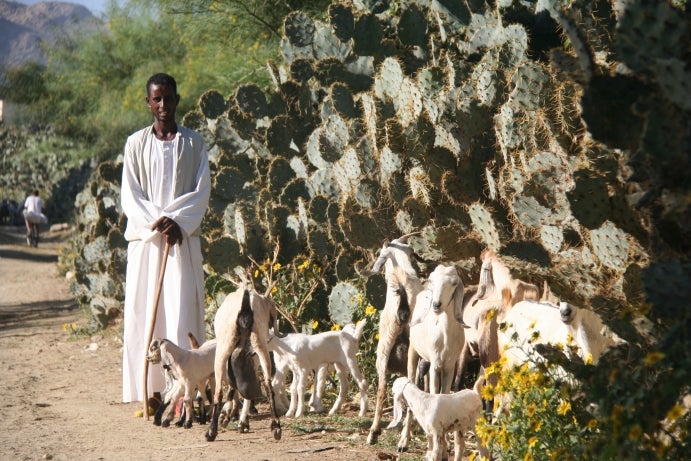

Keren shares much with Sudan to the north, most obviously long white galabias and generous turbans. Tea is delicious, and the staple brown beans of a good ful medames a siren call to those who’ve spent time in the region. Europhile Asmarinos consider Keren another country. That said, citizens cherry-pick cultural influences, maintaining a fondness for beer – particularly cheaper brews now pouring in from Ethiopia.

Monday morning’s livestock market is why most tourists travel to Keren: a shadeless, sandy expanse of goats, sheep, donkeys, cattle and camels, overseen by young boys waving sticks and squinting old men, stretches up a hillside. A commotion erupts as horned bulls fight in earnest, until a yelling youth wearing a galabia launches himself fearlessly into the fray, striking each beast smartly with his stick.

Elsewhere, camels are aloof and disdainful, though one male bull camel held in check against a wall angrily blows out a pink, fleshy air sack, and undoubtedly has murder in mind. Budget camels start at 15,000 nakfa, or around USD$1,000. I choose a seat in the shade, buying a glass of aromatic tea and some roasted peanuts.

The other city on the circuit is Massawa, Eritrea’s Red Sea port. Dropping from the 2,500m-high central plateau, initial rain showers bely the change in climate. More than 100km away, airy and cool, Asmara is soon a distant dream as Massawa’s humidity stupefies. A week earlier the city languished in 46-degree heat.

Despite being the country’s only port, Massawa is no hive of activity. The former Governor’s Palace, a one-time residence of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, lies in ruin, a reminder of past conflict. Not far away, the carcass of a Soviet Antonov cargo aircraft serves a similar purpose.

Beach life is 10 minutes from town at Gurgusum, where clear water and long stretches of sand draw weekend crowds. Mid-week, the modest Gurgusum Beach Hotel is almost deserted.

In a newer part of town, the Northern Red Sea Museum catalogues the region’s flora and fauna in pickling jars and skeletons. Other exhibits record history, ethnography and bloody campaigns of the liberation war.

Massawa’s old town remains beautiful. Along dusty streets, buildings constructed from coral stone reflect Ottoman, Egyptian and Italian occupations. However, many are empty and crumbling through war damage and neglect. The shattered shell of once opulent Banque d’Italia says it all. Here and there, cafes and bars trade discreetly, while industry appears limited to bicycle repair shops spilling into the streets.

Visiting Eritrea is a reflective experience, a country whose independence was paid for in blood, and whose development has been built on dreams and determination. Low crime, almost non-existent corruption and a powerful sense of nationhood are pitted against Byzantine bureaucracy, institutional paranoia and a hated system of indefinite National Service. However, peace has catalysed change. Whether this translates into political liberalisation is a question Eritreans now dare to ask.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Ethiopian Airlines flies to Asmara from Heathrow and Manchester from 11 December, via Addis Ababa, from £750pp.

Staying there

Undiscovered Destinations offers a nine-day Eritrea Discovery small group tour from £2,745pp; excludes flights.

Tourists travelling on UK passports require a visa which costs £50 and must be applied for in person, and by appointment, at the Embassy of the State of Eritrea at 96 White Lion St, London N1 9PF.