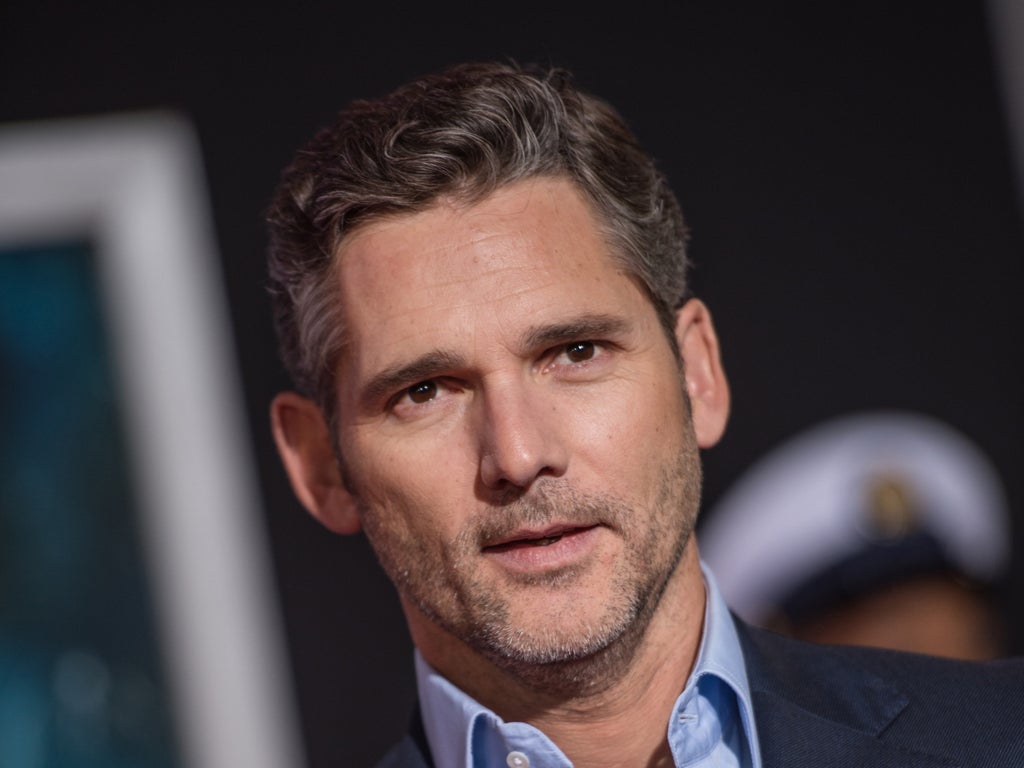

“I wouldn’t have wanted to be James Bond,” says Eric Bana. “It would have been too much fame for my head.” The star of Troy and Black Hawk Down was one of a select group of people who knew his Munich co-star Daniel Craig was being courted to play Bond back in early 2005. With his easy charisma, debonair looks and physical presence, he could easily have played 007 himself – only he had no interest in becoming one of the most famous men on the planet. “I’m largely able to do whatever the hell I want, whenever I want,” he says. “It would have been a great loss.”

More than 20 years on from his bravura breakout performance in Aussie cult crime classic Chopper, Eric Bana is still a reluctant star. One of the many Australian actors of his generation to find fame and acclaim in Hollywood, Bana has built an eclectic career that has seen him leading blockbusters, stealing scenes in Judd Apatow comedies and even making a devilish appearance as Henry VIII in The Other Boleyn Girl. Now with Chopper freshly remastered and re-released to belatedly commemorate the film’s 20th anniversary (thanks Covid), Bana has the opportunity to do something he doesn’t do often – reflect.

While Chopper became a slow-burn success, Hollywood immediately took note of Bana’s De Niro-esque transformation into the real-life Mark “Chopper” Read, a psychopathically bombastic lifelong criminal who makes Charles Bronson look like Hermione Granger. What followed was an impressive ascent to the highest echelons of Hollywood. Ridley Scott cast him as one of the leads in his exhilarating war epic Black Hawk Down; Ang Lee made him his Incredible Hulk; and Steven Spielberg had him carry Munich, his post-9/11 treatise on the futility of vengeance. He went from being a comedian unknown outside of Australia to one of the biggest stars in the world – but he always stayed rooted to his beloved Melbourne, where he has been able to take his kids to school in relative peace.

“I knew it was going to be short-lived,” Bana says of his early 2000s progression to Hollywood leading man. “I knew if it didn’t work out, it was back to doing whatever I was doing, which I was happy with.” Uneasy with fame, attention and paparazzi flashes, he’s still thankful his biggest role – in Hulk – largely had him hidden behind CGI. “On Hulk, nobody knew who I was. It was all about the director [Ang Lee], then it was about the big green guy and then me, I was kind of an aside.”

As it was the Hulk’s frowning face on all of the posters instead of Bana’s, he says he “never felt like the lead” on the film, which received a muted reaction upon release but in the years since has garnered high acclaim for its non-formulaic take on the character. After getting in on the superhero craze before they became cultural hegemony, Bana has no desire to return to making that kind of film. “You have to be careful what movies you choose to do because they’re like tattoos. I make the type of films that I enjoy watching. I think my filmography is reflective of what I like and what I don’t like.”

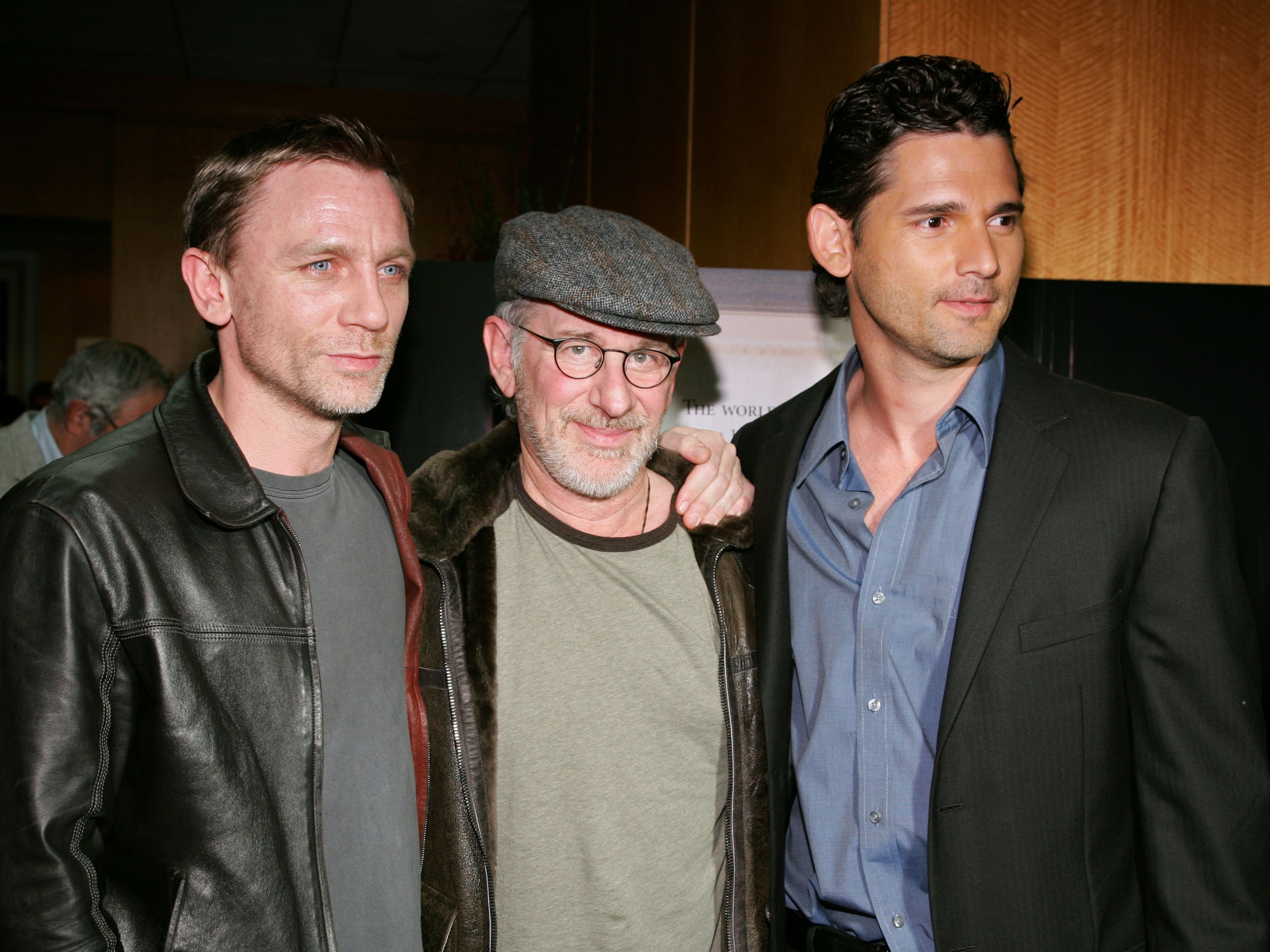

And he’s right. Look at the films he’s made and it’s hard to find “one for them”. He appeared in Special Correspondents because he wanted to work with Ricky Gervais, Lone Survivor because he’d read and connected with the book, and Star Trek because it was a chance to work with JJ Abrams and reinvent the most storied of sci-fi series. Although he refuses to “pick between his children”, the film he enthuses over the most is Spielberg’s masterful Munich, a mostly true-to-life recounting of the Israeli government’s determination to get vengeance for the massacre at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Getting to work with Spielberg was a “childhood dream” and “beyond believable”, but Munich, a nihilistically bleak parallel for America’s endless War on Terror, was polarising upon release. At the time, it was one of the Jaws director’s worst-performing films.

Bana anticipated the mixed reception, especially as the 7/7 bombings had happened earlier in 2005: “I knew that was going to be politicised and people were going to be talking about the politics of the film rather than the film, which is kind of exactly what happened. And so it took a long time for people to stop trying to prove how much they knew about politics, and to actually look at the film as a film – but that took quite some time. I think as people revisited it years later, it’s entered a different space to when it first came out.” Delayed acclaim is a recurring theme for many of Bana’s films. He jokes that he has a “special skill” for starring in movies that “aren’t appreciated” when they’re first released. Pretty much every notable film he’s been in, whether that be Chopper, Munich, Hulk or Hanna, has only garnered appreciation many years down the line.

None more so than Chopper, which eventually went from little-seen but well-received Aussie crime flick to renowned cult status, its poster finding particular favour among teenage boys. But it nearly never happened. Director Andrew Dominik had been searching without success for his Chopper for years, with names such as Russell Crowe, Richard Roxburgh and a then-unknown Ben Mendelsohn all rumoured for the role. None of them was quite right. Legend has it that Bana only fell on Dominik’s radar because the real-life Chopper suggested him for the role after watching his sketch comedy. It’s a nice story, but Bana isn’t sure it’s true. “I’ll never know if that was the sequence of events. All I know is that Mark didn’t veto me.” Still, there must be some truth to it – Chopper told Bana that after seeing his sketch comedy, “he realised I was insane enough to play him”.

Bana’s comic stylings are still largely unknown outside of Australia. In the mid-1990s, he wrote and performed on popular sketch show Full Frontal before getting his own series. Comedy was a happenstance for Bana. He was working odd jobs making ends meet when, during one bartending stint, bravery got the better of him and he did a trial stand-up set. From there, friends took him to some comedy clubs. He realised that most comics were “average and earning more than me pouring beer”, went away and wrote a five-minute set in a week. His comic ascent was as rapid as his dramatic one. It was this unorthodox entrance into the entertainment business and a lack of renown for his dramatic skills that unburdened him from the massive challenge of Chopper: “I didn’t have anything to lose. If I was a well-known dramatic actor, there would have been more pressure on myself. I just threw myself at trying to be him with nothing to lose.”

Hollywood has never really let Bana unleash his funny side. With the exception of Funny People, where he plays a love rival to Adam Sandler (the highlight of which is a scene where he gives a maniacally foul-mouthed tutorial about Aussie rules football), he’s been playing it straight. Not that he’s bothered about being pigeonholed one way or the other: “A lot of people say to me, ‘Dude you’re crazy, you’ve got to show these Americans what you can do,’ and I just don’t care. I’ve done it. I know I can do it. I don’t want to host Saturday Night Live because I live in Australia. I don’t have this nagging sense to prove anything.” These days, his comedy audience is his wife of 25 years, Rebecca: “Ideas float around my head and I tell her and we have a laugh but that’s the extent of it. Or we watch the TV and I start doing an impression of someone who’s p***ing me off. I get it out my system and I move on.” If the compilations of Bana’s sketches on YouTube are anything to go by, that’s our loss.

‘Chopper’ is in cinemas again now