Bill Magness sat in the Texas Senate chamber for several hours Thursday, defending himself and the Electric Reliability Corporation of Texas (ERCOT) that he runs. Senators grilled him about why the state’s once-obscure electric grid operator failed to prevent one of the worst power outages in U.S. history last week. ERCOT’s official mission as a nonprofit is “ensuring a reliable grid.” Instead, more than 4 million households lost electricity and heat in the middle of a severe winter storm. Texans across the state fought to survive in their freezing homes—many for days on end. At least three dozen people died.

“Texans suffered last week in ways they shouldn’t have to suffer,” Magness, who is president and CEO of ERCOT, told the state Senate Business and Commerce Committee. Magness said he felt “a great deal of responsibility and remorse” but insisted that ERCOT did “everything we could.” In hindsight, he said, he wouldn’t do anything differently.

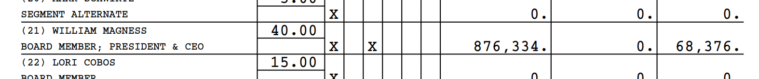

Yet despite repeated warnings that the grid wasn’t resilient enough for big storms, ERCOT leaders have failed to incorporate extreme weather events into their supply and demand models—all while Magness and other executives have collected increasingly high six figure salaries, according to an Observer review of the nonprofit’s tax records. Overall, total pay for executives and directors increased by 50 percent in the years following the last near-blackout in the state in 2011, from about $5 million in 2012 to $7.5 million in 2019. Over the last decade, ERCOT, along with the Texas Public Utilities Commision (PUC) that oversees the nonprofit, declined to require winterization at power plants across the state because the Legislature didn’t make standards mandatory. In November, ERCOT’s own meteorologist had advised the nonprofit of the potential for a catastrophic winter storm in 2021.

ERCOT operates Texas’ electrical grid—the only independent state grid in the country—directing electricity to 26 million customers, or about 90 percent of the state. Since 1930, the Texas grid has been disconnected from other states to avoid federal oversight, but that means Texas has limited support in a time of crisis. A harsh spotlight has been trained on ERCOT this month after its leaders abruptly ordered electricity providers statewide to shed load to avoid damage to the grid during the polar vortex.

Magness said ERCOT was forced to cut off vast swaths of the power grid in order to avoid a total system failure. Nearly 50 percent of its generation capacity was offline, he told his board members this week. ERCOT officials said at an emergency board meeting Wednesday that the grid operator was 4 minutes and 37 seconds away from collapsing.

After the last big freeze event 10 years ago, ERCOT reported financial losses between 2011 and 2015, tax records show. But the agency increased both its executive pay and its reported profits after Magness took over as the top executive in 2016. The agency’s total income and expenses fluctuated, but its net revenue of $34.7 million in 2019 was up 19 percent compared to 2016. ERCOT is funded by a transaction fee on power companies that use the grid.

In 2019, Magness’ salary was $876,334 according to the organization’s 2019 tax report to the IRS. Magness was already working for ERCOT as senior vice president during the 2011 Texas winter storm that produced a previous grid crisis. That year, he made $295,500.

ERCOT did not answer Observer questions about Magness’ pay. The organization also declined to make him available for an interview.

Twenty other ERCOT executives earned between $200,000 and $548,000 in 2019, the agency’s latest IRS report shows. Dwayne Rickerson, ERCOT’s vice president for Texas grid planning and operations, made $344,500 in 2019.

By comparison, Governor Greg Abbott makes $153,750, according to a state salary database posted by the Texas Tribune.

ERCOT’s available tax forms show it hired a consultant to provide information on executive pay and adjusted salaries accordingly, but the agency did not respond to questions about how much it paid that consultant or what nonprofits served as comparisons. However, The North American Electric Reliability Corp. paid its president and CEO $461,768, according to its 2018 tax form. (Its jurisdiction includes the rest of the continental United States, Canada, and the northern portion of Baja California, Mexico.)

Abbott has repeatedly condemned ERCOT for what he called its “total failure,” and said he “welcomed” the departure of the five board members who abruptly resigned this week (four of them lived out of state). “When Texans were in desperate need of electricity, ERCOT failed to do its job and Texans were left shivering in their homes without power,” he said. “The State of Texas will continue to investigate ERCOT and uncover the full picture of what went wrong.” Abbott has already made “ERCOT reform” an emergency priority this legislative session and vowed to investigate the corporation and what went wrong. But Abbott was silent on the culpability of the commissioners he elected to run the Public Utility Commission (PUC), which oversees ERCOT. It appears the buck must eventually stop with the Abbott and his political appointees.

In her testimony before the Legislature on Thursday, PUC Chair DeAnn Walker repeatedly tried to downplay the scope of her regulatory authority over ERCOT. However, in response to questions from Democratic state Representative Rafael Anchía, Walker eventually agreed with Anchía that PUC does have “total” oversight of ERCOT. Anchía pointed to ERCOT’s bylaws, which state that the corporation cannot pass a budget, hire a CEO, or install certain board members without permission from the PUC.

Among those who resigned was Peter Cramton, the board’s vice chairman who also serves as an economics professor at the University of Cologne in Germany. Cramton and several other board members drew an annual salary from ERCOT, too. His was $87,000 in 2019, tax records show. Another departing out-of-state board member, Terry Bulger, a banker who served as finance and audit chair, made $92,600 in 2019. ERCOT has also spent hefty sums on travel expenses each year: $1.2 million for travel and another $1.6 million for “conferences, conventions and meetings in 2019.”

ERCOT did not respond to a question about why it has recruited out-of-state members to serve on the board’s paid executive committee, but Magness acknowledged to legislators that conflicts of interest make it difficult to appoint qualified “unaffiliated” board members who reside in Texas. “If you’ve worked at Centerpoint your entire career and have a pension from them, you can’t serve as an unaffiliated member on ERCOT.”

Sally Talberg, of Michigan, one of the members who resigned her position, joined the board in January and had just been elected chairwoman on February 9. She previously served on the Michigan Public Service Commission, that state’s regulatory body that governs power generation. It’s unclear how much Talberg and the other out-of-state board members who resigned were earning at the time of the storm. A previous chairman made $100,000; not all board members are paid.

Talbert expressed hope at Wednesday’s board meeting that ERCOT would learn from this disaster and better plan for both for hotter summers and colder winters in ways that could serve other grid managers in other states too. “Texas is not alone in this regard,” she said. “All the models across gas and electricity need to be recalculated.”

At one point during the hearing on Thursday, Democratic state Senator John Whitmire asked Magness whether he thinks lawmakers should consider reforming ERCOT’s governance structure.

“Y’all made us,” Magness responded. “You should change us.”

Read more from the Observer:

-

Nine Texans on How They Survived a Frozen Week: After an unprecedented freeze swept Texas, the state’s grid approached a catastrophic blackout. Millions of Texans lost power or water—or both.

-

The ‘Culture of Violence’ Inside Austin’s Police Academy: Recent audits of the city’s cadet training spotlight a warrior-cop culture that pervades policing, even in a so-called progressive city.

-

Why Texas Wasn’t Prepared for Winter Storm Uri: A disaster management expert weighs in on how poor planning and communication failures deepened the crisis that left millions without power during the deep freeze.