If you are in energy poverty (or fuel poverty, as it is sometimes called), you or your household cannot afford to spend enough on the energy you need to cook, heat or light your home.

In Ireland, where I live now, energy poverty has a technical definition: if your household has to spend more than 10% of its income on energy, you are living in energy poverty. This is fairly typical as far as definitions go globally. Although there is no standard definition, you are generally said to be in energy poverty once energy costs account for a certain percentage of your income.

The lack of a standard definition means that for some people, energy poverty can mean going without luxuries. For others, it can be a question of life or death.

As someone who has experience of power outages lasting 22 hours a day in Pakistan, what I infer from these attempts to define energy poverty is the privilege of having reliable access to energy. Many researchers studying this problem take access for granted, which is not something you can expect in every place or situation. I have noticed this discrepancy at various high-level energy and climate conferences, including COP28 in Dubai.

Pakistan’s 2022 monsoon season brought a deluge that wrought floods and landslides, destroying roads and bridges and disrupting electricity, gas and telecommunication networks. Since the floods, there are still areas in the south of the country where it is common to find communities without electricity, natural gas or internet. I come from such a background, and for me, energy poverty has always been about whether I can expect power when I flick a switch.

It’s not like the energy is any cheaper in Pakistan. To address rapid inflation and currency devaluation, the Pakistani government recently secured a US$6 billion (£4.6 billion) bailout from the International Monetary Fund. In return, the government agreed to increase energy tariffs on households, leading to a sharp rise in utility bills.

Reliable access to energy is a matter of survival. As the temperatures rose in southern Pakistan during June 2024, so did the number of deaths among people who couldn’t simply turn on air conditioners.

Energy poverty in Ireland v Pakistan

Am I energy-poor according to the Irish definition of energy poverty?

No, I do not spend 10% or more of my monthly student stipend on energy. But do I prioritise comfort, convenience and my own health while consuming energy? No again. I organise my energy consumption very carefully and even follow a schedule from my provider that allows me to access 50% cheaper electricity at night compared with the day. Essentially, I save laundry, bathing, baking and often, heating, until the evening.

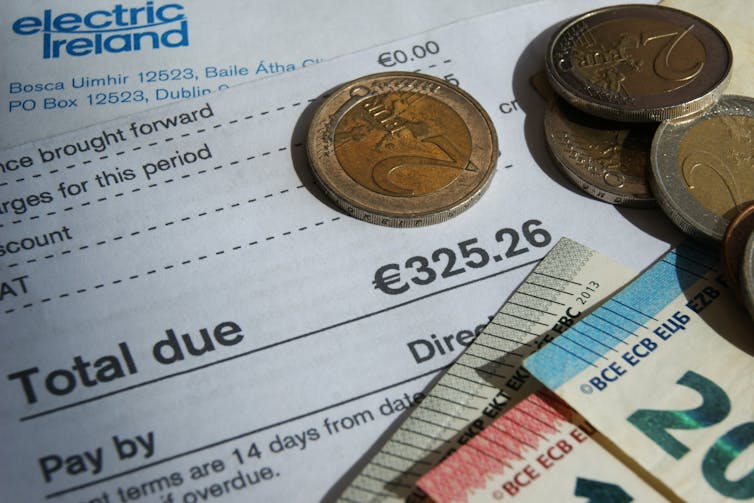

In each of the three winters I’ve spent in Ireland, our household has received €600 (£505) from the government to help pay for electricity. Unfortunately, this has been reduced to €450 (£378) for 2024. If I didn’t receive this subsidy, and if I turned the heating on during the day, I would certainly be energy-poor.

Would my family in Pakistan qualify as being energy-poor according to the same standards?

People in Pakistan often plan their daily chores according to when electricity is most likely to be available rather than how expensive it is. Power shutdowns lasting between ten and 12 hours are typical. Some areas suffer from blackouts lasting 22 hours.

The government even uses forced shutdowns as planned punishment for areas where electricity theft or non-payment of bills is common. In such a scenario, everyone suffers, and concepts like comfort are fanciful. It is pertinent to mention that, although Pakistan lies in a temperate zone generally, it is hot and dry near the coast. During July 2024 the “feels-like” temperature surged to 55°C in Karachi. Imagine surviving that without even a fan or water – you need electricity for both.

An average Pakistani spends almost 89% of their monthly income on utility bills, including electricity, water, gas and broadband. In Pakistan, a person is considered energy-poor if they are without traditional fuels like firewood, let alone cleaner and more efficient sources of energy like electricity.

On average, Irish people spend about 6.5% of their income on energy. So the average experience in Ireland is not energy-poor, as per the Irish definition, but in the US, a household that spends more than 6% of its income on energy would be considered energy-impoverished. Clearly, energy poverty means something different depending on where you live.

Since energy poverty is a complex problem, many researchers urge against defining it in terms of household income. Claudia Hihetah, a researcher at University College Cork’s energy, climate and marine research centre, recommends using “energy vulnerability” instead. She defines this as the struggle to access the energy needed for a dignified life and to meet your capability within a community.

Energy vulnerability feels like a more relatable concept for me as a Pakistani, and it chimes with my experiences while living in Ireland too. But even sticking with standard definitions, it seems ridiculous that a 4% difference in income proportion can mean the difference between poverty in the US and Ireland. We need a broader appreciation of what energy deprivation means for everyone.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 35,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Lala Rukh receives funding from the Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) for the ERBE Centre for Doctoral Training under grant agreement No 18/EPSRC-CDT/3586.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.