We think we know a lot about Australian and New Zealand soldiers’ health in the first world war. Many books, novels and television programs speak of wounds and war doctors, documenting the work of both Anzac nations’ medical corps.

Often these histories begin with front-line doctors — known as regimental medical officers — who first reached wounded men in the field. The same histories often end in the hospital or at home.

Yet, much of first world war medicine began and ended with the soldiers themselves. Australian and New Zealand soldiers (alongside their British and Canadian counterparts) cared for their own health in the trenches of the Western Front and along the cliffs of Gallipoli.

This “vernacular” medicine spread from solider to soldier by word of mouth, which they then recorded in diaries and letters home. It spread through written texts, such as trench newspapers and magazines, and through constant experimentation.

Soldiers presented a unique understanding of their experiences of illness, developed their own health practices, and formed their own medical networks. This formed a unique type of medical system.

Read more: Flies, filth and bully beef: life at Gallipoli in 1915

What was this type of medicine like?

Soldiers’ vernacular medicine becomes clear when looking at one significant example of war diseases — infestation with body lice — which caused trench fever and typhus.

The men’s understandings of the effect of lice on the body often contrasted to that of medical professionals.

Soldiers described lice as a daily nuisance rather than vectors of disease. The men sitting in the trenches were preoccupied with addressing the immediate and constant discomfort caused by lice, whereas medical researchers and doctors were more concerned with losing manpower from lice-borne disease.

Read more: Life on Us: a close-up look at the bugs that call us home

Many men focused on the endless itching, which some said drove them almost mad.

Corporal George Bollinger, a New Zealand bank clerk from Hastings, said: “the frightful pest ‘lice’ is our chief worry now”.

Australian Private Arthur Giles shuddered when he wrote home about the lice, noting it: “makes me scratch to think of them”.

Soldiers experimented

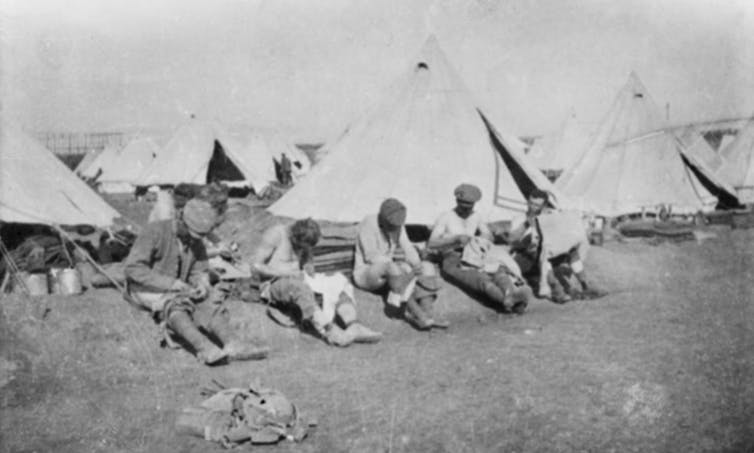

Soldiers’ reactions to lice, as a shared community, inspired them to experiment and share practical ideas of how to manage their itchy burdens. This included developing their own method of bathing.

When New Zealand Corporal Charles Saunders descended the cliffs to the beaches around Anzac Cove, he would “dive down and nudge a handful of sand from the bottom and rub it over [his] skin”, letting “the saltwater dry on one in the sun”. He also rubbed the sand across his uniform hoping to kill some of the lice eggs in the seams of his shirt and pants.

In some locations, fresh water was scarce and reserved for drinking. Without access to water, soldiers’ extermination methods became more offbeat, creative and original.

Men sourced lice-exterminating powders, such as Keating’s and Harrison’s, from patent providers — retail pharmaceutical sellers in the UK or back home in Australia and New Zealand — and rubbed various oils over their bodies.

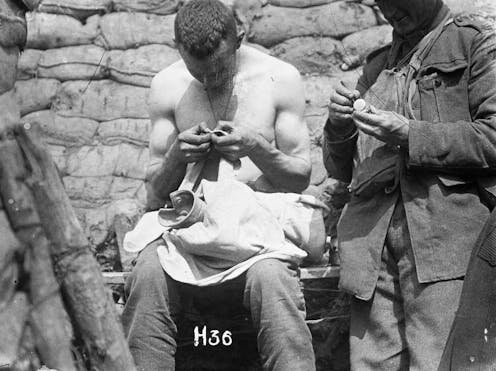

Yet, one of the most popular extermination methods was “chatting” — popping the louse between the thumbnails.

An Australian bootmaker, Lieutenant Allan McMaster, told his family in Newcastle it was “amusing indeed to see all the boys at the first minute they have to spare, to strip off altogether and have what we call a chating [sic] parade”.

Corporal Bert Jackson, an orchardist from Upper Hawthorn in Melbourne, took his “shirt off and had a hunt, and then put it on inside out”. He said that if he “missed any, the beggars will have a job to get to the skin again”.

Soldiers shared their knowledge

These soldiers shared their practices via their own medical networks, such as trench newspapers.

For instance, soldiers wrote humorous poems that also educated their fellow men. Australian Lance Corporal TA Saxon joked about lice-exterminating powders in his poem A Dug-Out Lament:

[…] They’re in our tunics, and in our shirts,

They take a power of beating,

So for goodness sake, if you’re sending us cake, Send also a tin of Keating.

One image from the trench newspaper “Aussie: the Australian soldiers’ magazine” came with the caption “Chatting by the Wayside” that drew on the well-trod joke about the double meaning of the word chatting.

What can we learn?

Reflecting on these often-overlooked aspects of the past helps us rethink medicine today.

For marginal groups in particular, access to professional health care can, and has often been, an expensive, alienating, or culturally foreign and abrasive task. So even in today’s globalised world, networks of non-professional medicine are as active as ever.

With many people isolated and at the mercy of much conflicting information, informal medical networks (often found on social media) present an opportunity to allay fears and swap information in a similar manner to how Anzac soldiers communicated via trench newspapers.

Perhaps some forms of vernacular medicine are occurring right under our noses.

Read more: The comfort of reading in WWI: the bibliotherapy of trench and hospital magazines

Georgia McWhinney received funding from the Federal Government of Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.