This article is part of the “Who would win?” series, where wildlife experts dream up hypothetical battles between animals (all in the name of science).

Of the giant prehistoric birds still wandering the planet, two of the top three largest live right here in Australia: the emu and cassowary.

The cassowary and emu are sister species, having diverged into separate species around 31 million years ago. These dinosaurs stand as tall as most humans and can weigh more than 40 kilograms, enough to dissuade most people from getting too close.

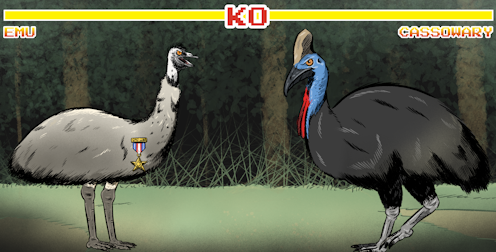

But how would they fare against each other, in a fight?

When two giants collide

For the most part, the emu and cassowary will never see each other.

The Southern cassowary is the only Australian cassowary species, and it lives in the rainforests of far north Queensland. It’s well suited to this dense, tropical habitat, and mostly survives on forest fruits. It’s known to fiercely guard its home range from neighbouring cassowary competitors, protecting its patch of resources.

The emu, on the other hand, is happy almost anywhere. Emus are “generalist” species — they’ll live in most habitats, eat almost any foods and travel between landscapes with ease.

But the only places where emus prefer not to travel is the far north of Australia, in harsh arid or tropical lands. This means emus and cassowaries overlap little in their natural distribution today, so a heated encounter is unlikely.

However, this may not have always been the case.

My recent research predicted that around 6,000 years ago, different rainfall patterns meant emus probably occurred further north along Australia’s eastern coast than they do today — right into cassowary territory.

So let’s step back in time, and see how a collision between the the two might have played out.

Meet the opponents

The heavyweight kickboxer

The cassowary is a stocky powerhouse. Its height is similar to the emu, but it is much heavier. While the emu might seem intimidating at 38-40kg, a cassowary’s kick has twice that weight behind it.

Weighing up to 80kg, a kick with the cassowary’s sharp claws would end any fight.

Cassowaries can be particularly territorial during mating seasons, where females fight for mates, and during chick rearing, when a solo dad protects his young. One short jump and down comes three sharp claws, with the innermost claw a 12 centimetre spike-like dagger.

If you’re a human, you’d be quickly tapping out. But what about an emu?

The power of speed

The emu might be a featherweight fighter compared to the cassowary, but what it lacks in weight, it gains in speed and agility. Granted, this speed and agility comes in handy, mostly, for fleeing. Why fight when you can outrun any opponent?

Their generalist, nomadic lifestyle means there isn’t much to be gained by staying and fighting. Instead, the emu will leave you in the dust, off at 50km per hour.

This might not paint emus as the bravest of megafauna, but they’re also armed with a decent set of claws. And they aren’t afraid to use them when it’s really necessary.

During breeding season, for example, females will battle each other to win the love of the best-looking males. Once those chicks arrive, dad emu won’t give you a chance to look twice at his stripy chicks.

The unlikely turf war

Now we know both emu and cassowary will use sharp claws when needed — especially new dads. Both species breed in winter, with new fluffy babies at their heel in early spring.

If an emu wanders into cassowary territory at any other time of year, it would be be off before the cassowary has time to swallow its fruit, not taking any chances by fighting the cassowary.

But today, dad emu has six chicks with him. So today is fight day.

While the chicks hide in nearby bushes, the emu picks up speed towards the cassowary. The cassowary stands its ground, stomping its feet and grunting to warn the emu.

The emu circles looking like it will take the cassowary by surprise. It lands a quick kick to the chest. But the cassowary kicks back. It’s a brutal blow, ending in a cloud of feathers and a terrified looking emu.

A taste of the power behind those short powerful legs makes it clear this is not the emu’s day. So he sprints away, with his chicks stumbling along behind.

The emu’s quick kicks are no match for the weight behind the cassowary’s kick and its enormous, daggered claw.

For the emu, no food, shelter or any other resource is worth risking a fatal blow from a cassowary. For the cassowary, resources are clustered and well worth protecting.

Read more: Who would win in a fight between an octopus and a seabird? Two marine biologists place their bets

The emu’s revenge: endgame

That might seem like a quick, unexciting knock out. But the emu is nothing if not resilient. The Great Emu War of 1932 will attest to that.

Emus were undeterred by the employment of the Australian military armed with machine guns to reduce their numbers. They outran and outmanoeuvred all military attempts to control them in pastoral land.

Since the loss of most Australian megafauna 46,000 years ago and changes in climate over the past 6,000 years, the emus’ range has expanded across most of the continent, assisted by its generalist nature.

The cassowary, on the other hand, has suffered a significant loss of suitable habitat. That loss, coupled with other threats such as collisions with cars, disease and feral predators, has tragically led to the species becoming endangered.

The cassowary might make short work of the emu one on one. But the resilient emu has the cassowary outnumbered by far. And a solo cassowary is no match for a mob of emus.

Julia Ryeland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.